January 27, 2022

Coming Together in Richmond City: Collective Bargaining Advances Equity and Strengthens Families

The City of Richmond is a dynamic community at the heart of our commonwealth. It is also one of the fastest growing cities in Virginia. Balancing the city’s rich history and diversity with a true reckoning of its past, Richmonders face a crossroads of deciding what sort of community they want the city to become.

Richmond’s public employees play a critical role in advancing the city’s priorities. Richmond’s public servants, the majority of whom are people of color, must receive fair wages and be empowered in their roles. The ability to bargain collectively will ensure public servants more equitable working conditions, improve worker retention, and improve public services as Richmond continues on its path to progress.

City employees in Richmond are currently underpaid and turnover rates are high

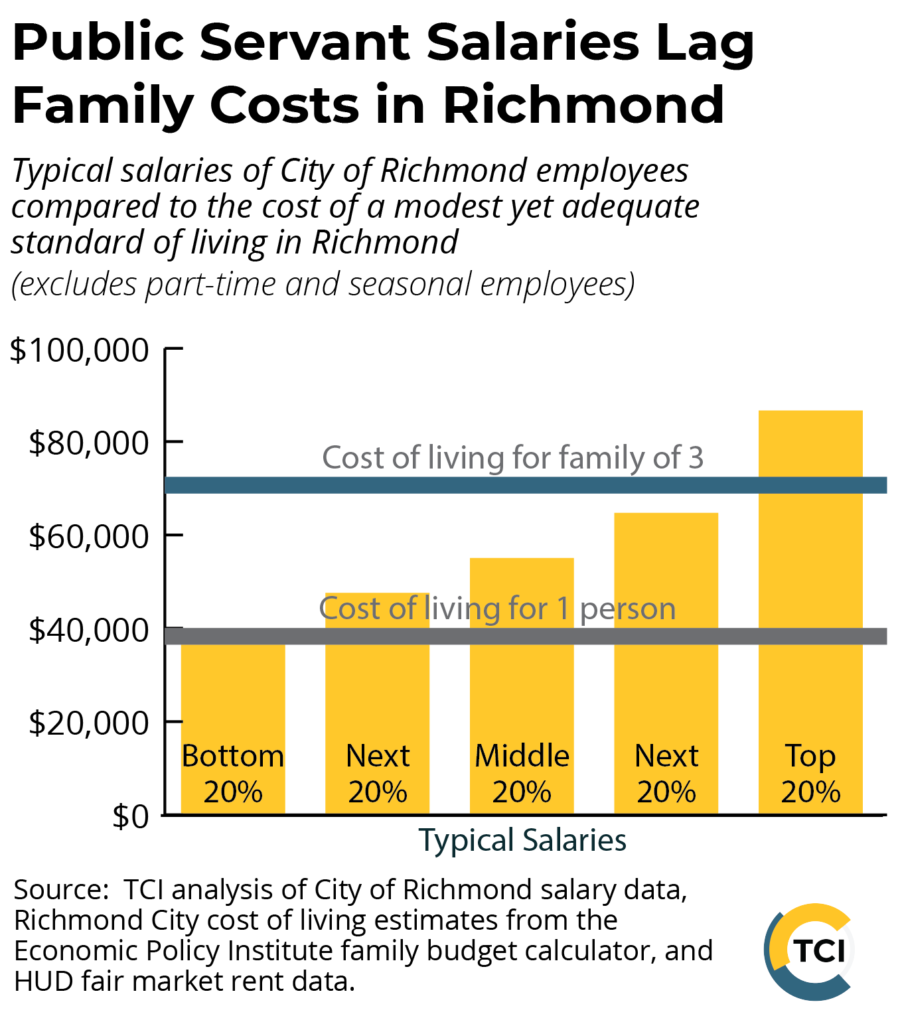

- Many Richmond City employees cannot afford to live in the city they serve. A review of city employee salaries shows that 1 in 12 of all full-time city employees could not afford to support themselves on their salary in the City of Richmond at a modest yet adequate standard of living. And more than 3 out of 4 could not attain an adequate standard of living on what they are paid if they have two children.1

- One in 8 general Richmond city workers who work full-time and year-round do not make enough to support themselves, and 4 out of 5 do not make enough to support a family. And the problem of low pay is not concentrated in a few departments.

- City employees who are Black and/or Hispanic or Latino are more likely to be paid low wages. One in 8 Black city workers were paid less than the cost of supporting themselves in the city they serve, and 86% were paid too little to support a small family of themselves and two children in the city. Similarly, 85% of Hispanic or Latino workers were paid too little to support a family. More generally, because 58% of city workers are Black, low wages for local public employees creates particular challenges for Black families and communities.2

- Local public employees in Virginia are typically paid 29.9% less than their private-sector peers with similar levels of education, age, and hours worked, one of the largest pay penalties in the country.

- Pension and health care benefits do not make up for these pay penalties. Employee benefits for local public employees in Virginia are less generous than in other parts of the country, and many private-sector employees, particularly full-time employees of large companies, receive generous benefits. For Virginia as a whole, the estimated total compensation penalty for local employees compared to their private-sector peers is 28.0%, close to the pay penalty of 29.9%.

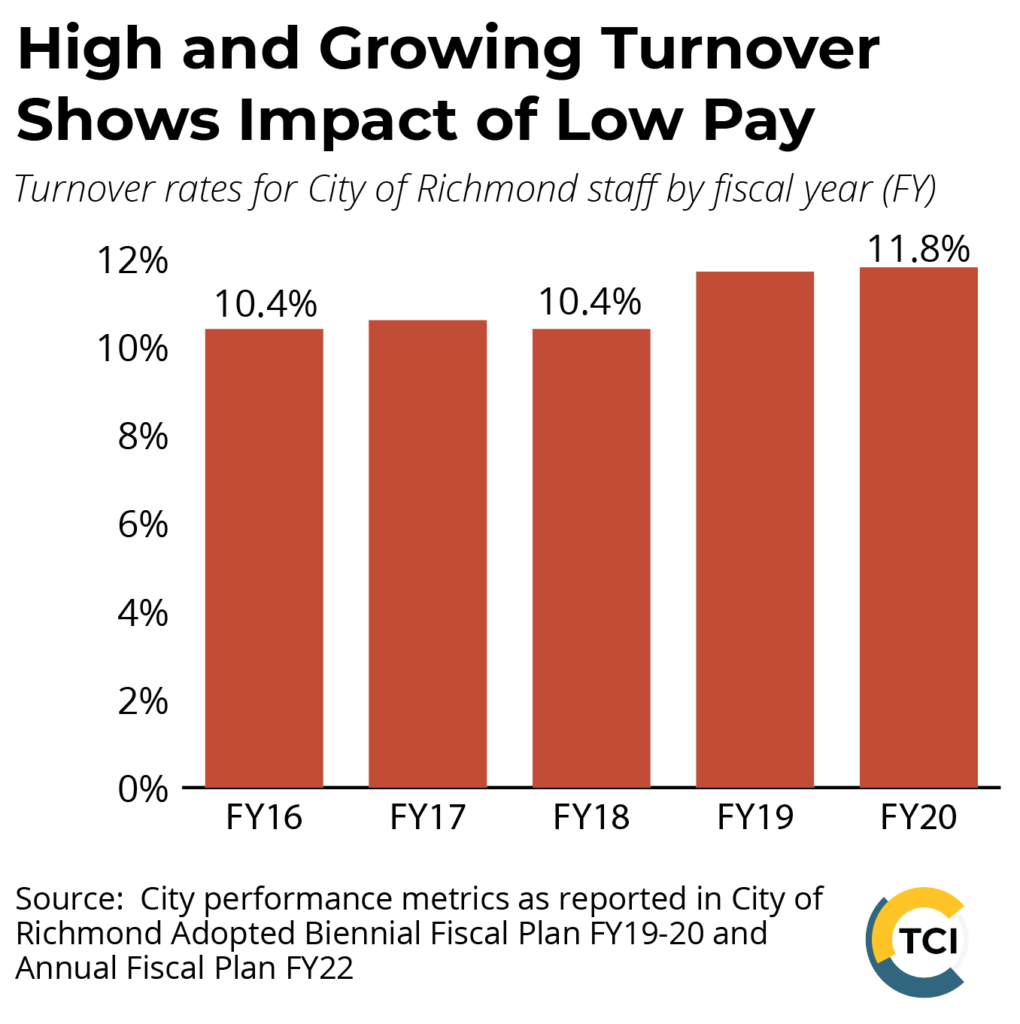

- The turnover rate for City of Richmond employees is high and remarkably expensive. In the budget year that ended June 30, 2020 (fiscal year, or FY, 2020), the city’s turnover rate was 11.8%, up from 10.4% in 2018. That costs money: One review of 30 case studies in 11 research papers found that turnover costs employers between 16% and 21% of an employee’s annual salary.3

- And the problem is not confined to one agency: the Office of the City Auditor reviewed the city’s employee turnover data from FY 2016 through FY 2020 and noted the median agency turnover rate was 11.3%. Using this median turnover rate and a conservative cost estimate of approximately $15,000 per employee, the city auditor concluded that employee turnover costs the city approximately $6.7 million per year.4 The city auditor also noted that while the city collects survey data on a quarterly and annual basis, the city does not have a retention plan or retention incentives.

Indeed, it is costly to replace workers because of the productivity losses when someone leaves a job, the costs of hiring and training a new employee, and the slower productivity until the new employee gets up to speed in their new job. Our analysis reviews 30 case studies in 11 research papers published between 1992 and 2007 that provide estimates of the cost of turnover, finding that businesses spend about one-fifth of an employee’s annual salary to replace that worker.

Heather Boushey and Sarah Jane Gylnn, “There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees, Center for American Progress, 2012

Collective bargaining reduces unfair pay inequities

Past discrimination and ongoing barriers mean Black workers, Latinx workers, and women of all races are still typically paid less than white men with the same level of education and experience in both public- and private-sector employment. Furthermore, women and Black people are more likely to choose public service jobs. Thus, addressing pay penalties for public employees is critical to addressing the broader problem of women and Black people being paid less than their peers with similar levels of educational attainment and experience.

For public employees, one of the benefits of unions is increased pay to levels that are closer to that which could be obtained in the private sector. Overall, public-sector collective bargaining tends to boost pay by 5% to 8%.5

“I’ve worked in the library for 28 years. I love what I do… I only recently started earning $17 an hour and that is still low. We have people who leave left and right because of the pay, the workload and the lack of communication. Something is not right and it’s not fair for people who have been here for years. With collective bargaining, things will be fair across the board when they are hiring, when they post positions, and when they move people up.”

Cynthia Jones | a Senior Library Technician, Richmond City Public Library systemWith regard to Virginia, local employees are typically paid 29.9% less than their private-sector counterparts with similar educations. States where public employees are allowed some sort of permission to collectively bargain have smaller pay penalties. In states with a policy like Virginia’s new law that allows – but does not require – localities to permit employees to collectively bargain, the average pay gap for local employees compared to their private-sector peers was 16.6%. The pay gap in states where collective bargaining rights for local employees are required and protected by the state was 10.5%.6

The fair and clear standards provided by unionization particularly further support Black and Latinx workers. It is not surprising that anti-union laws throughout the south were passed using explicit appeals to racist ideas. Unions are particularly important for raising pay for those who have historically been marginalized and underpaid compared to their levels of experience and education. Undoing that legacy will require proactive steps to create more equitable policies and workplaces.

Having a union provides a voice in the workplace and has a positive impact on democratic participation

The positive impact of unions is not limited to pay and benefits. Collective bargaining provides a way that represented workers can formally express their ideas for how to improve their workflow and workplaces. This can improve communication and a sense of belonging. Quantitative comparison of union members and non-union members finds that having the experience of collective bargaining and union representation in the workplace even makes people — particularly younger people and those with less formal education — more likely to participate in other systems of democratic governance such as voting.7

Collective bargaining is critical to ensuring an equitable future for Richmond

The city’s priorities and goals are impossible to achieve without the contributions of Richmond’s public employees, the majority of whom are people of color. Far too many of these public servants are underpaid and lack a democratic voice in their workplace. This dynamic only serves to advance already existing unfair pay inequities. Moreover, the turnover rates caused by this same dynamic costs the city millions of dollars a year.

Collective bargaining has been shown to increase wages, improve working conditions, and support worker retention. Public services and democratic participation also stand to benefit when workers are empowered in this way. It is time that the city’s public employees have the ability to bargain collectively so that Richmond can continue the progress it has already made.

Endnotes

- TCI analysis of 2021 salary data, EPI family budget calculator for a family of three, and FY22 HUD fair market rents. Pay and salary data includes both merit and non-merit employees and includes court employees and employees of constitutional officers. Results are similar when excluding court employees and employees of constitutional officers. Part-time and seasonal employees are excluded from this analysis. EPI analysis from 2018 shows that a single person in Richmond City would need an annual income of $36,560 to pay for housing, transportation, healthcare premiums and out-of-pocket costs, taxes, and other necessities. For a parent with two children, that amount is $69,055. TCI adjusted these amounts using FY22 fair market rents. The adjusted thresholds are $38,267 for a single adult and $70,645 for a parent with two children.

- This analysis by race excludes court employees and employees of constitutional officers such as the Sheriff’s Office.

- Boushey, H., and Glynn, S., “There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees,” Center for American Progress, Nov 2012

- City Auditor, May 27, 2021, ‘Human Resources Recruitment and Hiring Process Audit”

- Brunner, E., and Ju, A., “State Collective Bargaining Laws and Public-Sector Pay,” ILR Review, Mar 2019

- Morrissey, M., “Unions can reduce the public-sector pay gap: Collective bargaining rights and local government workers,” Economic Policy Institute, Jun 2021. This analysis used data from 2015 to 2019, before the state of Virginia permitted local governments to collectively bargain with their employees.

- Bryson, A., Gomez, R., Kretschmer, T., and Willman, P., “Workplace voice and civic engagement: what theory and data tell us about unions and their relationship to the democratic process,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 2013