October 4, 2022

Collective Bargaining: A Critical Tool to Improve School Staffing, Pay, and Morale

Every student deserves a high-quality education in a safe and healthy school environment that supports all aspects of learning. Teachers have a great impact on student outcomes, and improving conditions for teachers improves conditions for students. Yet factors such as low pay, challenging working conditions, and inadequate support are driving teacher and staff turnover while harming Virginia students. A key component to achieve a safe, healthy, and supportive environment for staff and students is allowing teachers and school staff to collectively bargain. Following the 2020 reversal of the state’s decades-long ban on local-level collective bargaining, each local school board in Virginia can now adopt a resolution that allows its teachers and school staff to engage in collective bargaining with its employees. By joining together to speak with a more powerful voice, collective bargaining can raise teacher and staff pay, increase retention, improve working conditions, and boost teacher morale. When teachers and school staff have a voice on the job, the overall impact is good for workers, students, and the community.

Teachers and school staff have attempted for years to have their voices heard and for their and their students’ needs to be met.

Image credits: Vertical Sandbox Productions

Inadequate pay, working conditions, and support drive teacher and staff turnover, harming Virginia students

National trends point to an urgent need for school districts to do all they can to improve conditions for their teacher workforce. Nearly 1 in 5 public schools reported having difficulty filling teacher vacancies a decade before the pandemic, and the problem only got worse in the intervening years.1

Three primary factors are driving the long-standing issue of teacher shortages, as summarized by the Economic Policy Institute:

- low pay relative to peers in other professions with similar credentials and experience,

- inadequate or uneven professional support for teachers, and

- challenging work environments.

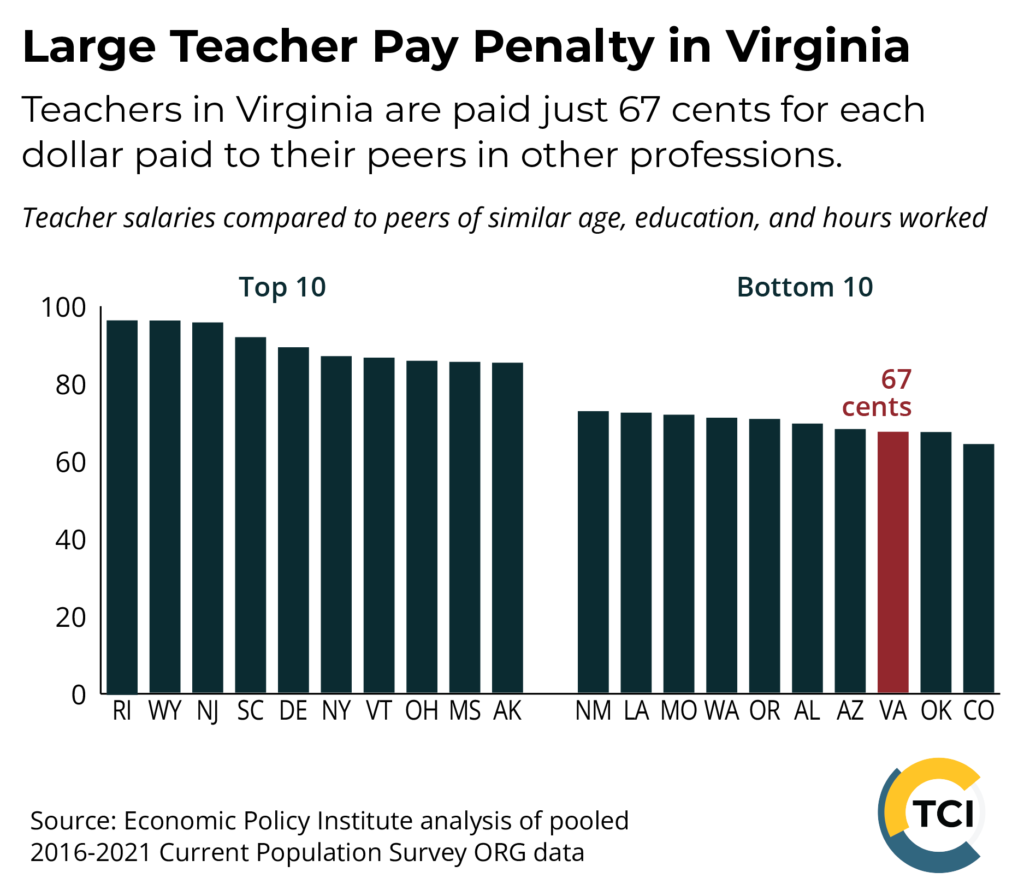

Virginia has not escaped these trends. With the third-worst teacher pay penalty in the country in 2021, Virginia teachers are paid 32.7% less — just 67 cents for each dollar — compared to their peers with similar education levels in other professions. (Virginia notably escapes the distinction of second-worst by only a fraction of a percent – the second-worst pay penalty is just 0.1% more severe.)2 And average teacher pay in Virginia ($58,506 in 2020-2021) is more than 10% below the national average ($65,293 that same year), even before adjusting for state differences in typical pay for professionals in other fields.3 Looking more broadly, local government employees in Virginia, which includes teachers and other school staff, are typically paid 29.9% less than their private-sector peers with similar levels of education, age, and hours worked, one of the largest pay penalties in the country.4

Low pay is also a reported factor in the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic shortages of support staff in Virginia. For example, school divisions across the commonwealth — in Northern Virginia, Central Virginia, Southwest Virginia, and Hampton Roads — have faced an acute bus driver shortage that mirrors national trends.5 In the 2021-2022 school year, 15.2% of full-time and 13.0% of part-time school bus driver positions were vacant. This shortage forces schools to compensate in ways that directly impact students, such as changing school hours and bus routes. Though bus drivers are the largest shortage by job function, over 1 in 20 of all full-time school support staff positions (“non-instructional personnel” such as reading specialists, counselors, and facilities staff) went unfulfilled during the 2021-2022 school year in Virginia.6

Low pay makes it financially challenging for young people in Virginia to choose to go into or stay in teaching and other school staff roles. Research shows that financial incentives are particularly important for attracting teachers to hard-to-staff schools. Teacher pay is also important for retaining existing teachers, which is critical for education quality. Teachers gain critical experience and skills over the first few years of their teaching careers, which has been shown in multiple studies to make them more effective. Experienced teachers also play a critical role as mentors for new colleagues. Low pay can result in experienced teachers leaving for jobs that better allow them to support themselves and their families.

Growing evidence suggests that the pandemic has caused increased demoralization and burnout among many teachers. Teachers across the board experienced a tremendous drop in their self-reported “sense of success” with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.7 And a national survey of those who left teaching during the first year of the pandemic found that the most common reason teachers cited for leaving was stress.8

Over half of U.S. educators are planning to leave the profession earlier than initially planned, with Black and Latino teachers being particularly likely to be considering leaving, according to another nationwide survey conducted by the National Education Association in January 2022. The high share of Black teachers who report that they are planning to leave their jobs is particularly concerning because diverse learning environments benefit students overall, particularly Black students from low-income households.

Collective bargaining is an effective solution for teacher and staff pay and retention

Improving Virginia’s public education system requires a multi-pronged approach, one of which is local school districts passing collective bargaining ordinances to give school staff a voice on the job.

We know that union strength impacts teacher pay. Between 1996 and 2012, non-unionized public school teachers were typically paid just 82.1 cents for every dollar paid to their non-teacher peers. Public school teachers that were unionized had a smaller pay penalty, receiving on average 86.8 cents for every dollar paid to their non-teacher peers, according to research published in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Monthly Labor Review.9 The results also have implications for gender equity – while unionization lifted wages in the public sector by 4.7% overall, it lifted wages by 7.0% for female teachers.10 On the other hand, legislative measures enacted in five states in 2011 and 2012 that restricted public-sector collective bargaining rights significantly reduced average districts’ spending on teacher compensation, including both teacher salaries and teacher benefits.11

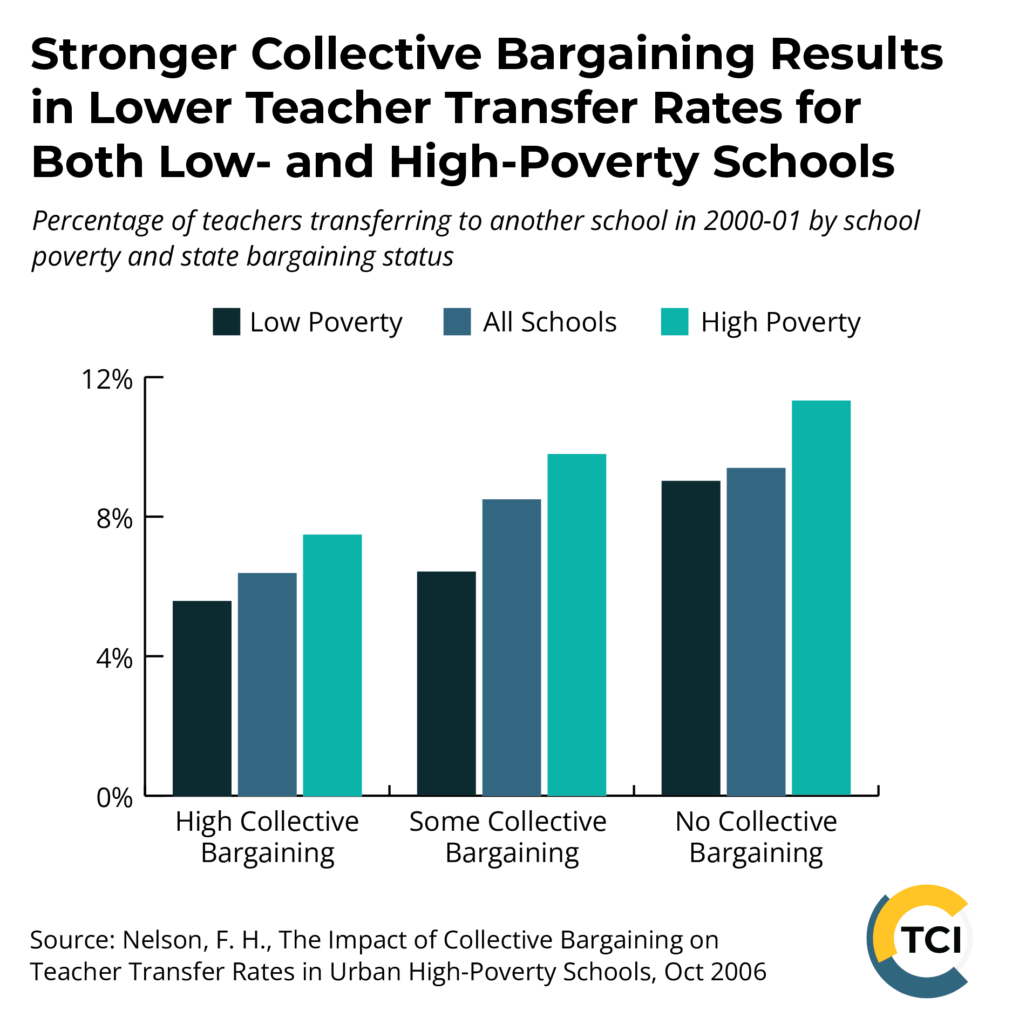

Schools with collective bargaining rights for teachers also have lower teacher turnover. A 2006 study from The American Federation of Teachers found that schools with collective bargaining have lower teacher transfer-out rates than schools without collective bargaining.12

Collective bargaining improves working conditions and teacher morale, allows more voice on the job

The ability to collectively bargain can also improve working conditions for school staff, which helps boost teacher job satisfaction and morale, as well as student outcomes. Unions serve as mechanisms for teacher voice and allow teachers to negotiate for enhanced protections and working conditions, according to findings from a study of over 1,200 collective bargaining agreements. Additionally, when state-level reforms limit bargaining negotiations, unions are weakened and are unable to compensate for the substantial reduction in working conditions.13

Working conditions are substantially associated with teacher job satisfaction,14 which in turn is highly correlated with teacher morale.15 Teacher morale has always been an important factor to success in the classroom, but classroom teachers and other school staff are under an unprecedented level of strain. This strain is made worse by the recent uptick in staff shortages impacting school systems across the country.

Collective bargaining is one approach with great potential to reverse this trend. Former Chesterfield Education Association President Sonia Smith has echoed this idea, telling the Chesterfield Observer in 2021 that empowering teachers through collective bargaining “would allow every school division to actually be far more efficient in its operations. You would see increased morale.”16 And Richmond educator Darrell Turner – one of the many Richmond school staff members who successfully organized to win the first local-level collective bargaining ordinance for Virginia educators and school staff – also affirmed that a collective bargaining resolution would lift morale and help retain and attract teachers when he testified to Richmond Public School Board members in 2021: “By passing a strong resolution, what you’re saying to educators is that we value you and we want your voice in how the school system is run.”

67.3

Cents paid to Virginia teachers per dollar compared to non-teacher peers*

on average, 2016-2021

*Non-teacher peers have equivalent levels of education and experience

82.1

Cents paid tonon-unionteachers nationallyper dollar compared to non-teacher peers*

on average, 1996-2012

86.8

Cents paid tounionteachersnationally per dollar compared to non-teacher peers*

on average, 1996-2012

Collective bargaining is good for student achievement

By boosting teacher pay, improving working conditions, reducing turnover, and increasing voice on the job, collective bargaining benefits students and communities as a whole. Higher teacher pay attracts higher-quality teachers, which positively influences student outcomes.17 Low teacher retention, however, negatively impacts student achievement for all students in school, with the strongest impacts seen in the reading and math outcomes for low-performing and Black students.18 Additionally, researchers and advocates have long recognized that teachers’ working conditions are students’ learning conditions. Research shows that when teachers have more voice on the job — that is, they are able to influence curriculum, professional development, textbook selection, and teaching methods — there is a positive correlation with student test scores.19 Weakening of teacher unions and their collective bargaining power in other states has been correlated with decreased student achievement.20

By boosting teacher pay, improving working conditions, reducing turnover, and increasing voice on the job, collective bargaining benefits students and communities as a whole.

Examples such as ABC Unified School District in California show that when employers and educators are able to come to the table in a collaborative way, the result is good for students. Through a strong labor-management partnership, the AFT Local 2317 president and the district superintendent have worked to dramatically improve the district. They have accomplished this through peer coaching, community partnerships, and programs that support professional development for teachers in schools with high numbers of special education students and English learners. As a result, students in the district have demonstrated significant growth in student achievement, including their reading levels and overall test scores.21 When local-level collective bargaining was being debated in Virginia’s General Assembly session in 2020, then-president of the Virginia Education Association Jim Livingston said to The Washington Post, “Apart from salary, this bill would let teachers negotiate things like improved technology, up-to-date textbooks, [which] have a direct impact on student learning…This is something that teachers have clamored for for many years.”22

Conclusion

Our public education system’s most valuable resource – its people – has long been forced to do increasingly more with increasingly less. And the COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the strain on teachers and school staff. Collective bargaining is a critical aspect of how to correct this dynamic, and it is now possible after the 2020 repeal of the ban on local-level collective bargaining in Virginia. Collective bargaining stands to boost wages and retention, improve working conditions and morale, and positively impact students by giving staff a voice on the job. It is time for all local school boards to support teachers and school staff by permitting them to collectively bargain.

Endnotes

- Cooper, D., and Hickey, S. “Raising pay in public K–12 schools is critical to solving staffing shortages,” Economic Policy Institute, Feb 2022; and García, E., and Weiss, E., “U.S. schools struggle to hire and retain teachers,” Economic Policy Institute, Apr 2019

- Allegretto, S., “The teacher pay penalty has hit a new high,” EPI, Aug 2022

- Gonzalez, M., “NEA Unveils New Nationwide Data on Educator Pay and School Funding,” National Education Association, Apr 2022

- Morrissey, M. “Unions can reduce the public-sector pay gap,” EPI, Jun 2021

- Deliso, M., “Why school districts nationwide are facing bus driver shortages,” ABC News, Aug 2021

- TCI analysis of the Virginia Department of Education’s Staffing and Vacancy report data

- Kraft, M., Simon, N., and Lyon, M., “Sustaining a Sense of Success: The Importance of Teacher Working Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University, Feb 2021

- Diliberti, M., Schwartz, H., and Grant, D., “Stress Topped the Reasons Why Public School Teachers Quit, Even Before COVID-19,” RAND Corporation, 2021

- Allegretto, A., and Tojerow, I., “Teacher staffing and pay differences: public and private schools,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review, Sep 2014

- Mishel, L., “Evidence shows collective bargaining—especially with the ability to strike—raises teacher pay,” EPI, Mar 2018

- García, E. and Han, E. “The impact of changes in public-sector bargaining laws on districts’ spending on teacher compensation,” EPI, Apr 2021

- Nelson, F. H., “The Impact of Collective Bargaining on Teacher Transfer Rates in Urban High-Poverty Schools,” American Federation of Teachers, Oct 2006

- Strunk, K., Cowen, J., Goldhaber, D., Marianno, B., Theobald, R., and Kilbride, T., “Public School Teacher Contracts and State-Level Reforms: Assessing Changes to Collective Bargaining Restrictiveness Across Three States,” American Educational Research Journal, Oct 2021

- Toropova, A., Myrberg, E., and Johansson, S. “Teacher job satisfaction: the importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics,” Educational Review, Jan 2020

- Lüleci, C. and Çoruk, A., “The Relationship between Morale and Job Satisfaction of Teachers in Elementary and Secondary Schools,” Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 2018

- Bass, S., “Teachers unions can now collectively bargain in Virginia. But is Chesterfield ready?” Chesterfield Observer, Oct 2021

- Dolton, P., and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O., “If you pay peanuts do you get monkeys? A cross-country analysis of teacher pay and pupil performance,” Economic Policy, Jan 2011

- Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., and Wyckoff, J.. “How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement,” American Educational Research Journal, Feb 2013

- Vachon, T., and Ma, J. “Bargaining for Success: Examining the Relationship Between Teacher Unions and Student Achievement,” Sociological Forum, Jun 2015

- Baron, E. J., “The Effect of Teachers’ Unions on Student Achievement in the Short Run: Evidence from Wisconsin’s Act 10,” Economics of Education Review, Dec 2018

- “ABC Unified School District,” American Federation of Teachers, Jun 2007

- Natanson, H., Virginia public school teachers poised to gain collective bargaining rights,” The Washington Post, Feb 2020