January 14, 2021

Set Up to Fail: How Court Fines & Fees Punish Poverty and Harm Black Communities in Virginia

Introduction

The fundamental role that Virginia’s courts play to advance justice, treat people fairly, and promote rehabilitation is made complicated by another task: raising revenue. In Virginia, court-imposed fines and fees too often set poverty traps, excessively burden Black communities, and affront basic notions of equal protection under the law.

In a quest for revenue from fines and fees, the judicial branch takes on the role of debt collector. While it is not especially successful at this task — in part because millions of dollars of debt are imposed every year on people who have no means to pay — the process creates a cycle of hardship for many people in Virginia. Unpaid court debt, even when resulting from low-level offenses, often leads to additional costs,1 court hearings, wage garnishments, and even deductions from state tax refunds. Overall, this system keeps people with limited financial resources tethered to the criminal justice system and pushes them further into poverty.

Like so many other aspects of the criminal justice system, race — explicitly or implicitly — is a factor that influences the level at which fines and fees are imposed. Prior research by The Commonwealth Institute (TCI) established that fines and fees are imposed at the highest rates by courts located in the areas with the largest percentages of Black Virginians. This report solidifies and expands our earlier findings, further illustrating the problems stemming from court-imposed fines and fees, with a special focus on criminal and traffic cases.

It cannot be lost that the data points in this report represent real people impacted by Virginia’s policy choices and whose lived experiences should help shape future solutions. In TCI’s conversations with people who currently owe court debt, a central theme was a feeling of being set up to fail. We heard frustration about how required payments are often set without asking whether someone can afford to make them. We heard confusion about how court fines and fees accumulate with little transparency. We heard dissatisfaction with the restrictive and inconsistent community service options, which for some can be a viable alternative to paying fines and fees. But most of all, we heard a concern from many people that even with their best efforts to pay, an unforgiving system would eventually ensnare them in more costs and more consequences.

Virginia’s policymakers should seize every opportunity to reform this system and set people up for success instead of failure. To aid in that effort, we offer several policy proposals — including a repeal of various poverty penalties that could serve as first steps toward a better system — all of which are shaped by experiences of Virginians with court debt who generously and bravely shared their stories with us.

Key Findings

- Even for the most minor offenses, fines and fees can result in significant debt that deepens poverty and keeps people tethered to the criminal justice system.

- There are striking racial disparities in how fines and fees are imposed: TCI found a strong, statistically significant relationship between the amount of fines and fees assessments per capita and the share of the population that is Black.

- Existing laws and policies set people up to fail, including through inconsistent access to payment plans, alternatives to payment, and the extra fees and burdens that punish Virginians with limited financial resources.

Acknowledgements

The Commonwealth Institute would like to acknowledge and extend sincere thanks to people at the following organizations for sharing their expertise, insight, feedback, and guidance throughout this project:

- The Fountain Fund in Charlottesville

- REAL LIFE Richmond

- Legal Aid Justice Center

- Vera Institute of Justice

By The Numbers: Fines & Fees in Virginia

Fines and fees serve two distinct purposes. Fines are intended to function both as punishment for the underlying offense and future deterrence.2 Virginia law generally sets out a permissible range that may be imposed by the court (e.g., “a fine of not more than $500”), while preserving the court’s discretion to order a lower fine based on the circumstances of the case. “Fees” or “costs,” by contrast, aim to generate revenue. Unlike fines, courts typically have minimal discretion to waive fees, meaning that — particularly for low-level offenses and traffic infractions — fees often account for the largest share of the total court debt imposed.3

In combination, fines and fees can result in significant court debt, even for minor offenses, and far exceed the amount intended to serve as the “punishment.” A $30 fine for an improper U-turn, for example, can balloon into a nearly $220 debt, especially for Virginians who cannot afford to pay upfront and must rely on payment plans, or who write a bad check during the payment process, or who — perhaps because of work conflicts or family obligations — miss a court date.

Fines and Fees Can Result in Significant Court Debt, Even for Minor Offenses

| Fine/Fee | Description | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Improper U-Turn | Fine set by VA Supreme Court’s Uniform Fine Schedule4 | $30 |

| Processing Fee | Applies to all traffic infractions | +$51 |

| Payment Plan Fee | Applies when more than 90 days are needed to pay the balance | +$10 |

| Bad Check Fee | $50 or 10% of the value of the payment, whichever is greater | +$50 |

| Credit /Debit Card Convenience Fee |

Adds 4% of the amount paid for the transaction, or a flat fee not to exceed $2 per transaction |

+$10 (assuming 5 payments of $2) |

| Failure to Appear Fee | Charged by the district court | +$35 |

| Total | $186 | |

| Collection Fee | When payment is delinquent for more than 90 days, the total balance owed increases by 17% | +$32 |

| Total with collection fee | $218 | |

Virginia’s laws are quick to pile on fines and fees, particularly for those who can least afford them, and slow to provide relief. For example, while courts have discretion to reduce and even waive court debt, this is only permitted by the statute after someone has defaulted on their payments and following additional court hearings. In other words, relief only comes at the bitter end, when someone fails to pay despite good faith efforts to do so — even then, relief is not guaranteed.

Year after year, Virginia squanders resources chasing after uncollectable court debt and imposing fines and fees at levels that lock people into cycles of debt they cannot escape.

Yet for all the hardship caused by fines and fees, they are only a minor source of revenue for Virginia. According to data provided to us by the Office of the Executive Secretary (OES) at the Virginia Supreme Court, fines and fees related to traffic and criminal cases netted the state treasury less than $200 million in FY19 — a modest sum in the context of Virginia’s $70 billion annual budget. The same data shows that fines and fees generated $757 million for the state treasury during that fiscal year, but the large majority of that revenue was related to land and deed transfers and certain other civil matters. It is important to note that while the dataset does not reflect fines and fees revenue that may bypass the state treasury and flow directly to localities or constitutional officers, it does make clear that revenue from traffic and criminal cases does not play an indispensable role in Virginia’s budget.

Data from the State Compensation Board (SCB) tells us something else: fines and fees are, and always have been, inefficient sources of revenue. This is because courts impose excessive fines and fees that many people simply cannot afford to pay. Multi-year trends highlighted in SCB reports show that much of what courts assess is never collected. For example, over the last five fiscal years for which data is available, the SCB reports show fines and fees assessments totaling more than $2.3 billion, but only $1.4 billion has been collected by the courts over the same time period. Efforts to collect on delinquent debt, a process led by the Commonwealth’s Attorneys, has also resulted in little success. Year after year, Virginia squanders resources chasing after uncollectable court debt and imposing fines and fees at levels that lock people into cycles of debt they cannot escape.

| Court Assessments & Collections From FY 2015 to FY 2019 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year | Assessed | Collected |

| 2019 | $468M | $296M5 |

| 2018 | $470 | $297 |

| 2017 | $470 | $291 |

| 2016 | $454 | $284 |

| 2015 | $429 | $251 |

| Totals | $2.3B | $1.4B (62%) |

The Impact of Race

Understanding and addressing Virginia’s fines and fees problem requires us to confront reality: fines and fees are imposed with unparalleled intensity in Black communities.

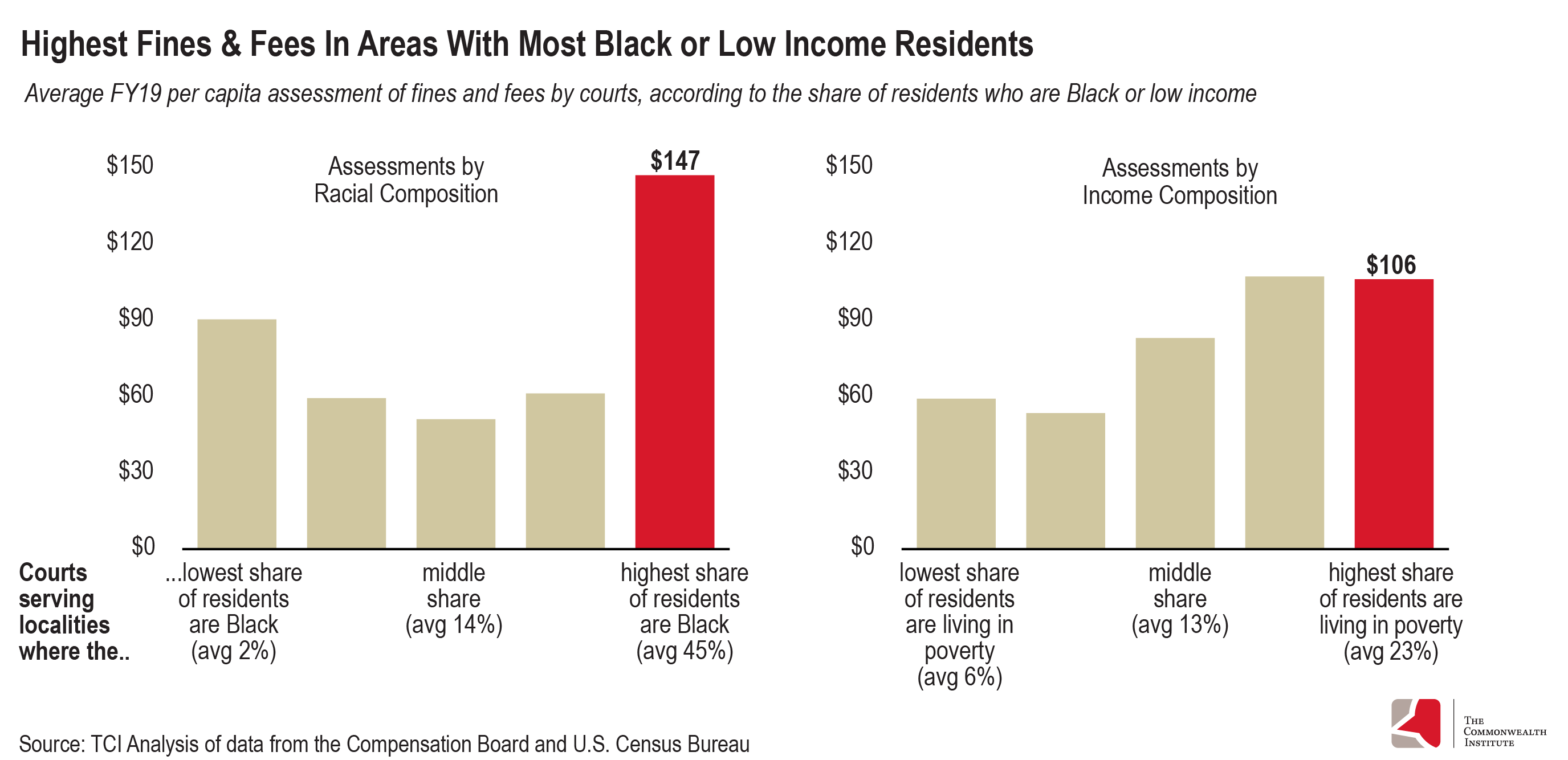

TCI’s prior analysis, based on a review of SCB data from fiscal year 2019, found that fines and fees are assessed at the highest rates by the courts serving localities with the highest share of Black residents and residents with incomes below the poverty line. Across all courts areas, an average of $82 was assessed in fines and fees on a per capita basis. But that number jumped to $147 (a 79% increase) in courts serving areas with the highest share of Black residents and climbed to $106 (a 29% increase) in courts serving areas with the highest share of people living in poverty.

Further analysis of this same data shows a strong, statistically significant relationship between the amount of fines and fees assessments per capita in a locality and the share of the population that is Black. Our regression model controlled for factors such as population size and poverty rates to show how race — as opposed to other possible factors — influences fines and fees. In the end, the results were clear: as the Black population share increases, fines and fees assessments per capita also increases.6

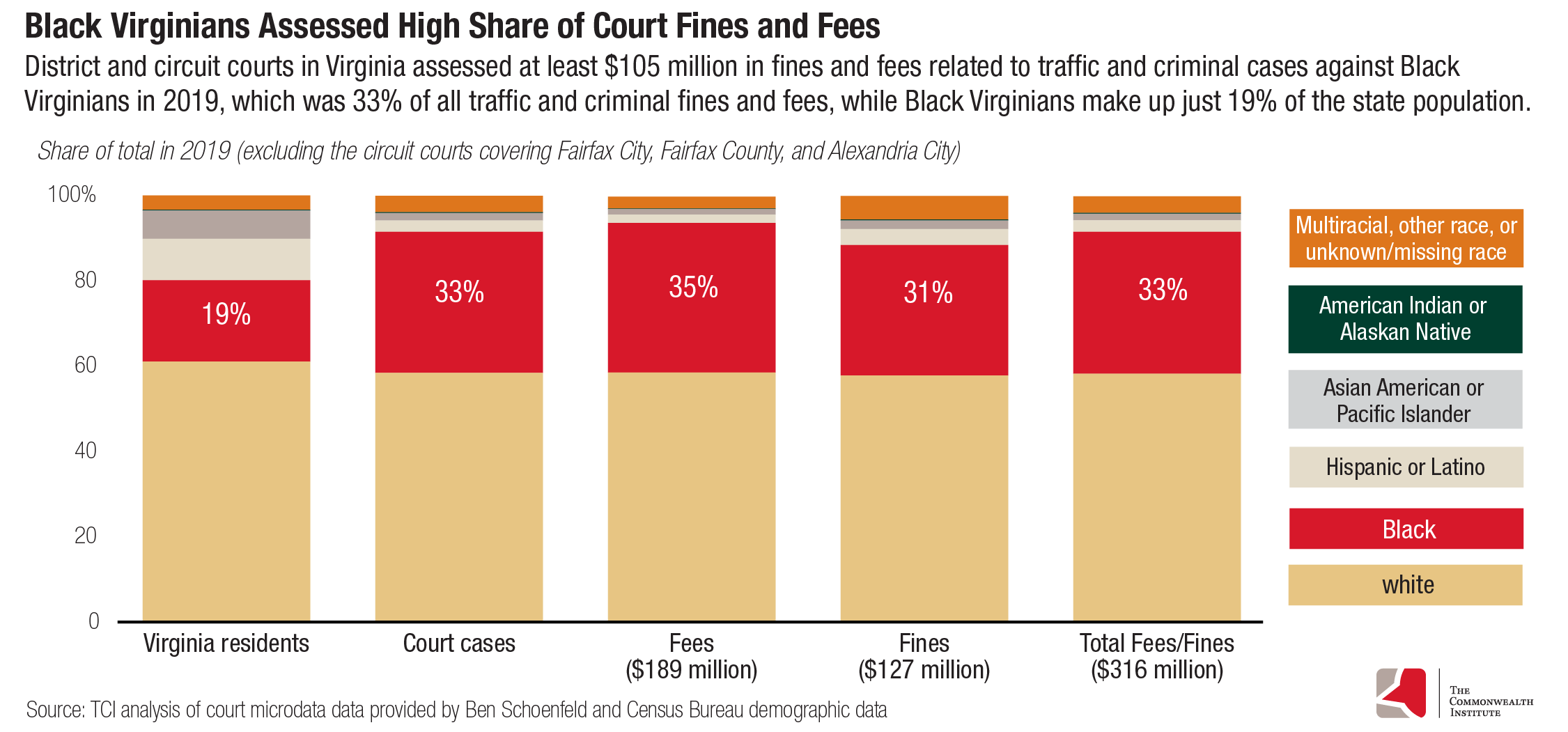

Aside from the SCB data, the excessive court fines and fees levied against Black communities can also be seen in the individual data of district and circuit court traffic and criminal cases. Of the $316 million in total fines and fees shown in the court microdata,7 the courts assessed $105 million against Black Virginians in 2019 — representing 33% of all traffic and criminal fines and fees, despite making up only 19% of Virginia’s population. This means, on average, that at least $65 in traffic and criminal fines was assessed for every Black Virginian in 2019, compared to an average of at least $31 for every non-Black Virginian.

The racial injustice underlying fines and fees — present in each of the data sources we analyzed — is an unsurprising byproduct of the broader racial biases in the criminal justice system. Police stop, search, and arrest Black people in Virginia at a much higher rate than their share of the population, and Black Virginians also face higher rates of pre-trial detention. Fines and fees are fast to follow. Overall, these stark differences in outcomes are not warranted by crime statistics; rather, they reflect the extent to which race impacts punishment in the criminal justice system. In this regard, Virginia is not unique. Several recent studies have similarly found that fines and fees are disproportionately imposed on Black communities across the United States.8

Set Up To Fail

The stress of managing court debt — whether hundreds of dollars or thousands of dollars, as was the case with some people we heard from — is made far worse by court rules and policies that are unrealistic and inconsistent. Too often, court ultimatums to pay ignore both the realities of poverty and the well-documented challenges that people with criminal records face when seeking employment opportunities. Moreover, the lack of uniform statewide standards on debt collection, as well as alternatives to payment, has produced an undeniable arbitrariness, guaranteeing that a person’s experience will be shaped less by their own circumstances and more by the courthouse they are standing in.9

Repayment Plans

Current Virginia law makes available various repayment plans and requires the courts to provide relevant information, in writing, to defendants when fines and fees are imposed. The law, however, also allows courts to establish barriers that can prevent some Virginians from participating in payment plans. For example, courts may charge a $10 “time to pay” fee for people who cannot afford to pay the entire balance within 90 days. The courts can also mandate a minimum down payment before entering a payment plan, which in some circumstances can exceed $50. In addition, although Virginia law states that the length of a payment plan should be “reasonable” in light of the person’s individual circumstances, some courts require people to file a petition and appear in court before a tailored plan can be made. These barriers are harmful not only because payment plans are most important to people who cannot afford to pay upfront, but also because interest begins to accrue on court debt after 40 days if no payment plan is made. In the end, people who can afford the least often end up owing the most.

Repayment Plans Vary across Virginia and Often Include Harmful Barriers

| Jurisdiction (General District Courts) | $10 Fee | Required Down Payment | Time to Pay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland | N | None (for first payment plan) | Up to $500: 6 months $501-1,000: 12 months $1,001 or more: 24 months |

| Fredericksburg | Y | 10% if balance is $500 or less; 5% or $50, whichever is greater, when balance exceeds $500. | Up to $499: 3 months $500-999: 6 months $1,000 to $2999: 1 year |

| Northampton County | Y | None (for first payment plan, if made within 30 days after trial) | Up to $300: 6 months Over $300: 12 months Extensions may be requested in person before the initial plan ends. |

| Newport News | Y | 10% if balance is $500 or less; 5% or $50, whichever is greater, when balance exceeds $500. | Up to $499: 3 months $500-999: 6 months $1,000-$2,999: 12 months $3,000-3,999: 18 months $4,000-4,999: 24 months $5,000 or more: 36 months A person may petition the court for an extension. |

| Petersburg | N | 10% if balance is $500 or less; 5% or $50, whichever is greater, when balance exceeds $500. | Based on an individualized assessment |

Community Service

As with court repayment plans, inconsistency permeates community service programs, which are — at least in theory — intended to help people “discharge all or part of the fine or costs” owed through service, rather than payment. While community service is hardly a realistic option for all, it is a viable option for some, but few courts — perhaps preferring payment — make this an attractive alternative. Without statewide standards governing the credit for one hour of service or even a shared definition of qualifying programs, the result is a patchwork of programs that treat people in Virginia in vastly different ways, even in nearby localities.

Patchwork of Community Service Programs Treats People Inconsistently

| Jurisdiction (General District Courts) | Hourly Rate | What’s Eligible? | Restrictions? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accomack | $7.25 (citing the state minimum wage) | “Non-profit organization” | Credit only awarded for the first 24 hours of service (up to $174) |

| Alexandria | $15 | Directs people to “Volunteer Alexandria” for referrals | Unspecified |

| Charles City | $10 | “A non-profit agency or organization that benefits the community,” including SPCA, fire stations, Habitat for Humanity, etc. | Requires documentation of service to be submitted on “letterhead stationary,” signed by the supervisor |

| Cumberland | $7.25 (citing the federal minimum wage) | Unspecified | Requires a motion and court hearing before approval |

| Greensville | $7.25 | A nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization, includes examples of food banks, Red Cross, Goodwill, United Way. | Court decides whether to approve community service hours after they have been completed |

| Richmond City | $15 | Unspecified, but must be “authorized by the court in advance” | Unspecified |

Additional Burdens For People Who Were Formerly Incarcerated

Virginia places extra burdens on people who are reentering their communities following a period of incarceration. Despite the existing rule that “no interest shall accrue on any fine or costs imposed” during the time a person is incarcerated, that grace period does not happen automatically. Instead, the individual must complete specific forms, obtain paperwork from the Department of Corrections, or the state or county jail, and submit all materials to a court clerk. These steps must be repeated in each court where debt is owed.

Many of the people TCI spoke with who were previously incarcerated were not aware of this process, suggesting that many Virginians are paying interest that accrued during a period of incarceration. In other cases, we heard about how difficult and burdensome this process can be, given the many challenges people face after a period of incarceration, from securing housing to obtaining employment. It is beyond reason to expect the thousands of people released from incarceration every year in Virginia to either navigate this process successfully or else pay interest that should not be imposed in the first place.

Policy Recommendations

Over the longer term, a priority for Virginia’s lawmakers — given clear racial disparities and the damage to judicial credibility — should be eliminating court fees that lock people into cycles of debt. The courts serve the general public and they should be funded through state and local appropriations, rather than through fees which place a heavy burden on those without means to pay. In the short term, state policymakers can implement a handful of “first-step” reforms that set more people up for success rather than failure.

- Eliminate Poverty Penalties. As discussed above, extra fees and burdens are often imposed on those who can least afford to pay, which jeopardizes their economic security. Virginia’s lawmakers should pursue the following common-sense reforms:

- Repeal the $10 “time to pay” fee for people who need more than 90 days to pay their court debt.

- Eliminate mandatory down payments, which can exceed $50 and create barriers to participation in court repayment plans.

- Ensure any interest that accrues on court debt while an individual is incarcerated is automatically waived upon their release. Currently, the law requires the person to navigate a burdensome process to waive the interest.

- Expand Data Collection & Reporting To Understand Racial Disparities. The Virginia State Compensation Board should be required to collect and publish data pertaining to the assessments and collections of fines and fees by race and ethnicity, as part of their existing annual reporting obligations. Publishing this data will help policymakers understand and address the disproportionate harm to Black communities from fines and fees.

- Strengthen Ability to Pay Assessments & Community Service Alternatives. While judges have some discretion to reduce court debt, it is generally not an option until after someone defaults on payment. Instead, courts should have clearer power at the outset to waive fines and fees at the time they are imposed, particularly for Virginians who have no means to pay or for whom payment would create a economic hardship. This reform is in line with recommendations from the American Bar Association10 and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.11 Additionally, while community service is not a realistic option for everyone, at minimum there should be common standards across all courts and programs for those who do choose to pursue this alternative. The credit for one hour of service varies dramatically across Virginia. For fairness, there should be a uniform rate— for example, double Virginia’s minimum wage — that applies to all qualifying programs. In addition, service options should be expanded, including the development of online options, which is even more important in the context of a health pandemic.

Building on Recent Momentum

In recent years, Virginia’s General Assembly has demonstrated that it can deliver meaningful reforms in this area, including ending the suspension of driver’s licenses for unpaid court fines and fees. State lawmakers have an opportunity to build on that momentum and uproot poverty penalties and racial disparities that have characterized Virginia’s system of fines and fees.

Methodology Note

This report uses data from three different sources in order to provide a more complete picture of fines and fees in Virginia.

- Assessments are the amount of fines and fees that an individual is charged in relation to a court case in a particular year. Revenue and collections are the amounts that are actually collected in a particular year, some of which may have been assessed in prior years.

- The Supreme Court of Virginia Office of the Executive Secretary (OES) revenue data includes revenue that was collected by Virginia courts that flowed to the state treasury. This excludes any direct revenue for localities and constitutional officers that does not flow through the state treasury.

- The State Compensation Board (SCB) Fines and Fees report includes summary information on assessments and collections of fines and fees. This data excludes “tax-like” revenue such as recordation taxes, but in some cases includes restitution and collection fees for delinquent debt.

- The court microdata, which was collected and provided by independent data scientist Ben Schoenfeld, includes assessments of fines and fees in criminal and traffic cases, but does not include data for the circuit courts covering Fairfax City, Fairfax County, and Alexandria City.

Endnotes

- For example, revenue code 499 increases the amount owed on delinquent accounts by 17%. Circuit Criminal Manual – Appendix B, Office of the Executive Secretary, Jul 2020

- “Targeted Fines and Fees against Communities of Color: Civil Rights and Constitutional Implications,” U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Sep 2017

- Code of Virginia § 16.1-69.48:1. For traffic citations, for example, there “there shall be assessed as court costs a fixed fee of $51.”

- Rules of Supreme Court of Virginia Part Three B, Traffic Traffic Infractions and Uniform Fine Schedule, Last amended by Order dated June 4, 2020; effective July 1, 2020

- The SCB and the OES data appears to include different revenue, with the OES data only including revenue that goes to the state treasury and the SCB excluding “tax-like” fees (for example, recordation taxes) but likely including some civil fees. As a result, there are differences in the total fine/fee revenue in the different data sources.

- TCI performed a regression analysis using jurisdiction-level data from the Compensation Board that was merged with U.S. Census Bureau demographic and poverty data. In our preferred model, local poverty rates and population size are included as control variables to attempt to account for other community-level differences that could drive differences in assessments per capita.

- TCI analysis based on court microdata gathered by Ben Schoenfeld. This analysis excludes circuit court cases from the Fairfax and Alexandria circuits due to missing data, but includes all district court data. District courts account for 75% of all fines and fees shown in the microdata. Excluding residents of Fairfax County, Fairfax City, and Alexandria City, 21% of Virginia residents are Black.

- See for example, Sances, M. & You, H., “Who Pays for Government? Descriptive Representation and Exploitative Revenue Sources,” Sep 2016; “Targeted Fines and Fees against Communities of Color: Civil Rights and Constitutional Implications,” U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Sep 2017; “Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department,” United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Mar 2015

- “Driven Deeper Into Debt: Unrealistic Repayment Options Hurt Low-Income Court Debtors,” Legal Aid Justice Center, May 2016

- “Ten Guidelines on Court Fines and Fees,” prepared by the ABA Presidential Task Force on Building Public Trust in the American Justice System, Aug 2018

- “Targeted Fines and Fees against Communities of Color: Civil Rights and Constitutional Implications,” U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Sep 2017