August 28, 2018

In Funding High-Poverty Schools, Virginia Gets a Failing Grade

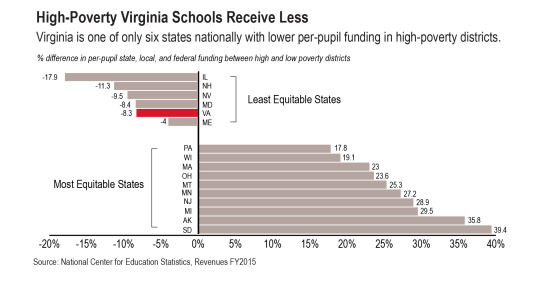

Virginia is one of just six states in the nation where the wealthiest school districts receive more funding per student than the poorest districts, according to a new report from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Summarizing 2014-2015 school year data, the report shows that the richest 25 percent of Virginia school divisions collect $13,199 in revenue for each student on average, while the poorest 25 percent of Virginia school divisions collect $12,182 per pupil. That means schools in high-poverty communities receive around 8.3 percent less funding per student (state, local, and federal combined) than schools in the wealthiest areas of the commonwealth.

Another national report card from earlier this year used similar data to give Virginia an “F” in funding distribution to poor school districts, and “C” and “D” grades in K-12 per-pupil investment relative to state fiscal capacity. In short, Virginia is far too wealthy to justify the relatively small amount of state money it dedicates to schools in struggling communities.

Part of the problem is that Virginia could contribute more state funding to schools generally.

In 2016, localities in Virginia raised about $6,700 per student, the 14th highest per-pupil amount in the nation. In state revenues, however, Virginia ranked 42nd at around $4,900 per student. As a state with a relatively high fiscal capacity (we rank 20th in GDP per capita), the state isn’t doing as much as they could to fund K-12 education with state funds.

Increasing state funding for K-12 schools overall would not necessarily solve the problem alone. The commonwealth has a responsibility to ensure that the quality of a student’s education isn’t dependent on the size of their community’s tax base. To address this, states can direct funding to divisions in higher poverty localities. Several states successfully do this at much higher rates – Montana, Minnesota, Michigan, South Dakota, Ohio, New Jersey, Alaska, and Massachusetts all generate at least 20 percent more per pupil in their poorest districts (combined state, local, and federal) than in their richest districts, and 35 others raise at least equivalent amounts between the poorest and richest quartiles.

Virginia does target some extra state support to schools with high percentages of low-income students through its At-Risk Add-On program, which provides between 1-13 percent more in basic aid per student eligible for free lunch. But given the funding gap that this new national report reveals, this approach is clearly not sufficient to make up for the difference between high-poverty and low-poverty school divisions.

Rather than relying so heavily on student enrollment to allocate state funding to school divisions, Virginia should follow the lead of other states that use need-based allocations. This model would use weights to adjust per student funding based on economic status, English language proficiency, or student disability. Most states take this approach to more equitably distribute education funding to divisions. Absent adding this method to its funding strategies, Virginia should expand the At-Risk Add-On to make up for the difference. During the 2018 General Assembly session, lawmakers introduced a bipartisan budget amendment to increase the Add-On amount to 1-18 percent per student, but the effort was not included in the governor’s, House, or Senate versions of the budget. Lawmakers did include a more modest increase of the program from lifting the maximum percentage from 13 percent to 14 percent in FY 2020.

Adequate school funding plays a crucial role in closing the opportunity gaps between students in low- and high-income families. Studies have shown that increasing per-pupil spending improves test scores, educational attainment level, and even earnings as adults, especially for students from low-income families. In a July presentation to the Board of Education, the Virginia Department of Education presented findings from one study that suggested that the poorest quintile of divisions in Virginia would have to spend $6,623 more per student to reach national achievement standards. That money can’t primarily come from local revenue.

Significant new state revenues from a growing economy, changes to online sales tax policies, and conforming to federal tax legislation mean that lawmakers could have the resources to support improved investments in high-poverty school divisions throughout Virginia.

Category:

Education