June 8, 2020

Virginia Can Choose Equity for School Funding During Economic Crisis

Executive Summary

Now more than ever, parents, families, and communities are reminded of the critical role that educators and schools play in developing young minds, caring for children’s health and safety, and allowing our economy to function and grow into the future. Despite doors being closed for the remainder of the school year, highly consequential decisions are being made by state and local leaders that will have significant and lasting impacts on students now and long after they return to the classroom.

It is critical that Virginia leaders learn from mistakes made during the last recession when students in higher-poverty communities saw the biggest funding reductions in their schools, both in Virginia and across the country, and these cuts significantly stalled or harmed their learning and development opportunities. For example, recent research shows test score impacts following the last recession were larger for children in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates, and spending cuts widened disparities in test scores between Black and white students.

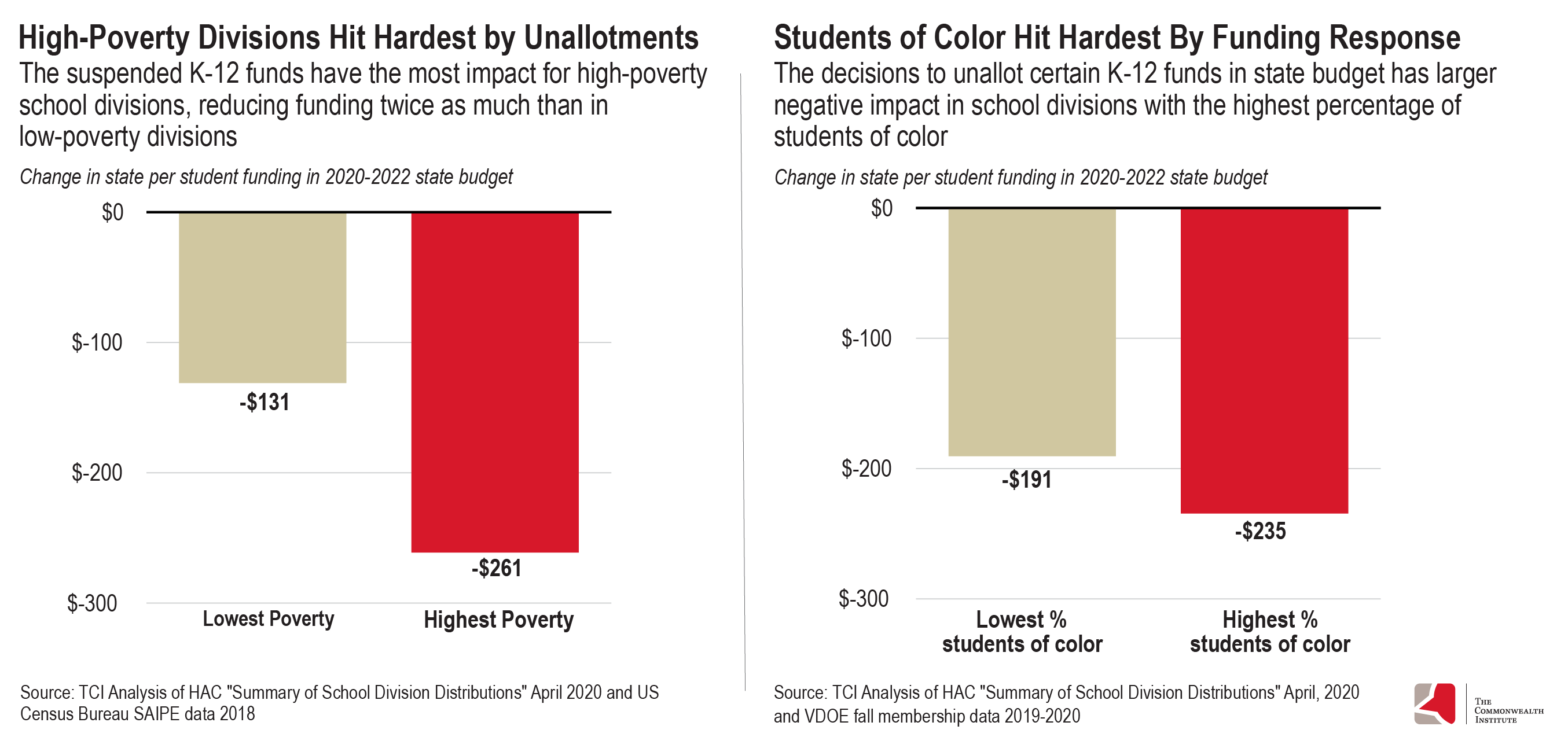

The recent budgetary action taken by state lawmakers starts Virginia down the same troubling path. Gov. Northam proposed and state lawmakers acted to temporarily suspend $490 million in early education and K-12 funding. The suspended funds for school divisions with the highest child poverty rates are twice as large per student as they are for the lowest-poverty school divisions, and there are also larger impacts for school divisions with the greatest share of students of color. Divisions with the highest percentage of students of color will lose out on 23% more per student than school divisions with the lowest percentage of students of color.

These reductions mirror the mistakes of the past recession. This initial approach may have been taken for simplicity, given the uncertainty and challenges the state faces due to the COVID-19 pandemic, yet it does not have to be the final decision. State lawmakers will likely take action on the state budget later this year in a special session when they have a clearer picture of state revenues. Early reports already indicate large declines in state revenues, which could signify even further reductions to school funding in a special session. To avoid this outcome, federal aid is desperately needed, and state leaders can take action by modernizing Virginia’s revenue system to avoid a cuts-only approach to the budget. Lastly, when tough budget decisions must be made, state lawmakers should take into consideration the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic impacts of their proposed changes to school funding.

The current approach will result in spending reductions falling on the backs of the students, teachers, and families who are already asked to do more with less and face the greatest barriers to learning during this crisis. Virginia can and should take a more equitable approach to school funding.

Impacts from the Past Recession on Funding and Student Outcomes

Funding Impacts

There are well-documented consequences from school funding cuts that occurred in the aftermath of the Great Recession, both nationally and here in Virginia, showing our highest-poverty communities were most adversely impacted. K-12 funding declined sharply starting in 2008, as shown in a national report by the Albert Shanker Institute. Yet funding in the highest-poverty school districts dropped 7.5% from 2009 to 2013, while it fell just 4.1% in the lowest-poverty districts. The inequity was even worse in Virginia where state funding dropped by almost 3 times more per student in the highest-poverty divisions than in the lowest over that same time period.

Some states eventually restored their K-12 funding during the subsequent 11 years of economic growth to pre-recession levels. Unfortunately, Virginia was not among them. State per-student spending was still down 8% in the 2019-2020 school year, which was significantly reshaped by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The choices made by policymakers in response to the last recession were of a structural nature and have kept funding cuts in place on a permanent basis, long after the recession was over. Many of the cuts, including the cap that was placed on state funding for support staff, were not one-off solutions that would automatically be removed when the economy recovered. Instead, they were permanent changes to Virginia’s primary school funding formula, the Standards of Quality, and lawmakers are required to revise the formula in order to reverse course. Ten years after the Great Recession, lawmakers continue to leave the support cap in place, which in turn, costs local school divisions hundreds of millions in state aid each year.

While reductions in state funding as a result of the budget cuts were universal, the impacts in terms of actual staffing were much more severe for students of color. School divisions with the highest share of students of color saw their staffing levels drop more drastically than other divisions with the lowest share of students of color. Support staffing dropped by 4 positions per 1,000 students in divisions with the highest percentage of students of color compared to a decrease of 1 position per 1,000 students in divisions with the lowest percentage. In total, support staff declined by more than 600 positions in divisions with the most students of color, while enrollment has grown by almost 16,000 students.

Student Outcomes

The nationwide decline in per-pupil spending coincided with the first national average test score decline in the past 50 years, both in math and reading assessments, and slowed growth in first-time college entrants. The stalled progress on National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) assessments has led to the period after 2009 being labeled the “Lost Decade” in educational progress.

The consequences of these funding reductions are felt more by students in higher-poverty communities and by students of color. The Great Recession presents a clear moment in which school funding changed, and recent national studies show the impacts of school funding reductions on student outcomes. A recently updated study by economist Dr. C. Kirabo Jackson uses this moment to assess the impact of school spending with data from 50 states. The analysis finds reductions in school spending during the Great Recession coincided with declines in NAEP scores and college-going rates, and the test score impacts were larger for children in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates. The spending cuts also widened disparities in test scores between Black and white students.

Similarly, research recently published by the American Educational Research Association found declines in test scores were greatest for students attending school in counties most adversely affected by the Great Recession. The declines in student achievement were particularly pronounced for students in school districts with a higher share of students living in low-income families and for students in schools with a higher share of Black students compared to districts with a lower share of students from low-income families and lower share of Black students. They did not find a relationship between outcomes for Latinx students, or publish impacts on other races or ethnicities.

The impacts from the last recession are clear. Students in higher-poverty communities saw the biggest funding reductions in their schools, both in Virginia and across the country, and these cuts significantly stalled or harmed their learning opportunities. In particular, these spending choices disproportionately harmed Black students across the country.

Suspended Funds In State Budget Have Inequitable Impacts

The recent budgetary action taken by state lawmakers threatens to lead Virginia down the same troubling path of 2009 and would have similar and inequitable results for Virginia students. In response to the economic crisis as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, Gov. Northam proposed and state lawmakers acted to temporarily suspend $2.3 billion in new and discretionary spending in the 2020-2022 state budget. This action “unallots” these funds – meaning they will not be funded in the budget, unless re-enacted by the General Assembly in a special session later in the year.

The funds that were unallotted include $490 million in aid for early education and K-12 schools. The General Assembly had voted earlier this year to substantially increase Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On program, which directs resources to school divisions with the highest concentration of students from low-income families, to help address Virginia’s long-standing inequity in school funding, and that funding has now been suspended. Other unallotted investments include resources for the Virginia Preschool Initiative ($91.5 million) and increasing students’ access to school meals ($10.6 million). These investments aim to strengthen support for the very students who have long faced barriers to receiving a high-quality education and who will be most impacted by the missed educational opportunities resulting from the current crisis.

If these important investments are not restored, Virginia will once again venture down a path where school divisions with the highest share of students from low-income families and highest share of students of color will be the most harmed by lost revenues in an economic downturn. In fact, the suspended funds for school divisions with the highest child poverty rates are twice as large per student as they are for the lowest-poverty school divisions — $261 per student compared to $131.

There are similar impacts for school divisions with the largest share of students of color. Divisions with the highest percentage of students of color will lose out on 23% more per student than school divisions with the lowest percentage of students of color — $235 per student compared to $191 — across the biennium.

State lawmakers will likely take action on the state budget later this year when the economic and budget picture becomes clearer. The research is clear that reductions (and increases) in school funding have the largest impact on outcomes for students from low-income families and the current proposal has dramatically larger reductions in aid for the students in communities with the most poverty. Rather than sweeping unallotments, a different approach is needed, and lawmakers should take into consideration the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic impacts of their proposed changes to school funding.

Equitable Approach to School Funding Needed Going Forward

The choices Virginia lawmakers make over the coming months will have lasting impacts on our schools and students, as shown by the last recession, and it’s critical lawmakers use every tool available to prevent similarly deleterious impacts on students. Some strategies state policymakers can and should take, include:

- Ensure Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Equity in School Funding Choices

- Seek Additional Federal Assistance

- Raise State Revenues

Ensure Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Equity in School Funding Choices

School funding amendments taken up in the special session should be examined for how they will impact different student groups. As previously discussed, this equity consideration was not taken during and after the last recession, resulting in much larger funding reductions for students in the localities with the highest child poverty rates and where the research shows cuts cause the most harm. Rather than going down that road again, lawmakers should work with money committee staff to ensure that spending choices do not result in disproportionate harm to school divisions with the most students of color and most students who live in households with low incomes. As our analysis shows, the current unallotment strategy does both.

The Learning Policy Institute’s (LPI) school funding priorities for states include many of the investments that have been unallotted or taken out of the budget. Their guidance directs states to “double down on equity-focused investments,” which is what Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On does by directing resources to the school divisions with the most students eligible for free lunch. LPI recommends that states “attend to social and emotional needs of students and staff,” which includes access to school counselors and social workers. They also suggest states “sustain access to early care and education.” These services are made possible in Virginia through the Virginia Preschool Initiative (which provides early education to children from lower-income families). Virginia has many mechanisms in place to adequately support our students, though we must fully leverage them in order to respond to this moment and to provide a high-quality education for every student.

Rather than taking out funds for the At-Risk Add-On or Virginia Preschool Initiative, there needs to be a more holistic review of the state budget. State lawmakers can look to make use of federal resources, draw upon Virginia’s two reserve funds, and adopt new state revenue options. If lawmakers are still forced to reprioritize within the K-12 budget, then funding cuts should not be at the expense of the students, teachers, and families who are already asked to do more with less and face the greatest barriers to learning during this time.

Seek Additional Federal Assistance

The federal aid to state, local, and tribal governments included in the CARES Act is far short of what is needed to address the upcoming budget challenges. Nationwide, state budget shortfalls could total $765 billion over three years as estimated by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in May, based in part on economic projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). There are negotiations happening in Congress on a potential fourth stimulus, although this effort has stalled in the Senate. One proposal has already passed the House called the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act. It is absolutely critical for the federal government to provide additional assistance to state and local governments to navigate the immediate and long-lasting impacts the pandemic will have on state budgets.

Raise State Revenues

Undoubtedly, we will have a lengthy economic recovery ahead. State lawmakers must consider revenue raising options to make sure we can make investments in our schools after the additional federal aid is no longer available. During the last recession, several other states asked those who could most afford it and profitable corporations to pay more. Virginia was not one of them, instead relying on major cuts to our education system that were never fully restored. If we want to live up to our promise of providing a high-quality education, then we need to seriously consider asking Virginians who have benefited the most from our strong economy to start paying their fair share. Supporting communities through well-funded schools helps build an economy and communities where everyone can reach their potential.

By making smart choices like fixing our upside-down tax code and raising new revenue, as opposed to relying solely on harmful cuts to the state budget, Virginia can choose equity during this crisis and avoid repeating the lingering mistakes made in response to the Great Recession. There is a better path forward for supporting our students and advancing educational opportunity even in challenging times.

Methodology Note

For the purposes of this report, high- and low- poverty school divisions are defined using the Census Bureau’s Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) for children aged 5 to 17 in 2018 (the most recent data available). High- and low- share of students of color are defined using VDOE’s fall membership data for the 2019-2020 school year. Divisions are placed into five groups (quintiles) based on child poverty percentage and student of color percentage (all nonwhite students with a racial or ethnic identification). Divisions are placed into groups so each group has similar average daily membership. The report discusses the difference between the extremes — lowest and highest groups.