February 14, 2020

A Regional Minimum Wage Would Accelerate Inequality In Virginia

Imagine three people who are paid minimum wage: one is based in northern Virginia, another in the City of Richmond, and the last in Hampton Roads. All three share the same employer, hold the same job title and responsibilities, and have identical education and experience. They are equals, in every respect, except for their pay. While all three are “minimum wage” workers, the northern Virginia worker is paid the most, the Richmond worker is paid less, and the Hampton Roads worker is paid the least. The gap between the highest paid worker and everyone else grows each year, such that they will never catch up.

This approach — one that treats minimum wage workers differently based on geography — is prohibited under current law, which establishes one minimum wage across Virginia. But Senate Bill 7, as currently amended, would open the door to scenarios like the one above by creating a “regional” minimum wage. If enacted, Virginia would have one of the most complicated and inequitable minimum wage laws in the country.

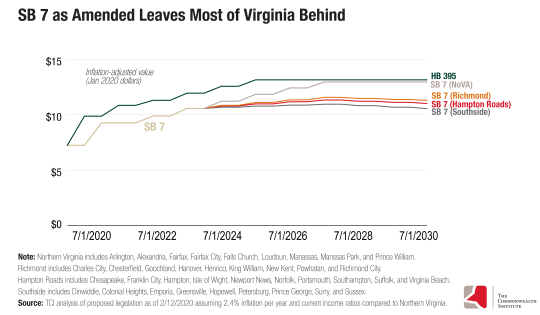

Let’s take a closer look. Under SB 7, Virginia’s minimum wage would increase to $9.50 on January 1, 2021, followed by $1 increases in 2022 and 2023. By July 1, 2023, the minimum wage would reach $11.50 across Virginia. After that, the Commissioner of Labor and Industry would carve the commonwealth into “regions” and establish different minimum wage rates beginning on July 1, 2024. The region with the highest median household income — i.e., the wealthiest region — would receive a $1 annual increase to their minimum wage, while every other region — i.e., poorer regions — would receive less. Based on this formula, the gap between the highest and lowest regional wage would only increase over time, accelerating income inequality among Virginia’s lowest-wage workers.

The authority of the Commissioner to establish regions is a profound grant of power, one with real consequences for millions of working people in Virginia. While it’s unclear how these regions might take shape, consider this: median household income is highest in Northern Virginia (Planning District 8), where it rises to about $120,000. That’s compared to roughly $70,000 in the Richmond area and $62,000 in the Hampton Roads area. For every $1 increase to the minimum wage in northern Virginia, Richmond would receive 58 cents and Hampton Roads would receive 51 cents.

On this trajectory, Northern Virginia would reach a $15 minimum wage by 2027 in nominal dollars ($15 will buy less than in 2020 due to the effects of inflation). By then, working people based in Hampton Roads, for example, would already be earning $1.95 less per hour, or $4,000 less per year. For households with low incomes, that’s a significant amount of money that could help cover major expenses like health insurance ($2,555 per year), food at home ($3,656 per year), or utilities ($3,200 per year). But these families would only fall further behind: While northern Virginia’s minimum wage would be fully adjusted for inflation each year to keep up with rising costs of living, lower-income regions would only see a partial adjustment, even though inflation rates are actually significantly higher for working people who are paid low wages. Assuming an annual inflation rate of 2.4%, Richmond and Hampton Roads likely would not see a $15 minimum wage until 2032, or even later.

What about differences in the cost of living? Does that justify paying some minimum wage workers less than others?

At $7.25, Virginia’s minimum wage has been stuck for a decade. In a sign of how dramatically working people have been left behind, minimum wage employees today earn less per hour than their counterparts did 50 years ago, after adjusting for inflation. In Virginia’s most “affordable” locality — Danville City — a single adult must earn $14.90 per hour (in 2018 dollars) to make ends meet. Even with a universal $15 minimum wage that is phased in over several years, many families — in both urban and rural areas — will still struggle to afford basic necessities, even though they will be in a much stronger position relative to a minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

Regionalism would also set back working people of color and women

One focus of this legislative session has been to eliminate aspects of Virginia’s minimum wage law that are tangled in the history of Jim Crow. For example, House Bill 395 would remove the exclusions for domestic service workers and agricultural workers that currently leave them out of minimum wage protections. Separately, the Senate also voted to end certain discriminatory exclusions, including for domestic workers (SB 804) and piece workers (SB 78). But an unintended consequence of SB 7’s regionalism is that Black workers could again be left behind, as only 23% of Black people in Virginia live in the area that would likely receive the largest minimum wage increase.

This means the vast majority of Black workers in low-wage jobs would be systematically excluded from the strongest feature of SB 7: a guaranteed $1 increase in the minimum wage until $15 per hour is reached. Many of Virginia’s majority-Black cities and counties such as Greensville and Sussex are in Southside, which has one of the lowest regional median incomes and therefore would see some of the smallest increases in the minimum wage. Overall, by undercutting the minimum wage, a regional approach would make it more difficult to close the wage gap between white and Black workers. In 2018, Black workers in Virginia were paid 71 cents for every dollar paid to white workers.

At the same time, regionalism would fuel gender inequality by lifting the wages of fewer people. This is because the majority of working people — nearly 60% — who would benefit from raising Virginia’s minimum wage to $15 statewide are women. The gender wage gap in Virginia is already stark: women are paid 79 cents for every one dollar paid to men.

All working people in Virginia should see at least a $15 minimum wage

For all of these reasons, 48 states do not have a regional minimum wage. Though New York State has taken a regional approach, their law converges — rather than diverges — wages over time until everyone reaches $15. Oregon also has a regional minimum wage, but the regions are defined by statute — rather than by a Commissioner with broad discretion — and the law has safeguards to prevent runaway inequality. At the federal level, where the case for regionalism arguably should be the strongest given the diversity of the national economy, the bill passed by the House of Representatives (H.R. 582) last year rejected the idea. That was in part because a federal regional wage would have excluded more than 15 million working people, over 40% of whom are working people of color.

The fundamental challenge with SB 7’s regionalism approach is that it does more to cement inequality in Virginia than to establish a baseline minimum wage that lifts up all people who are paid low wages. After waiting more than 10 years for a raise, working people in Virginia deserve better. At the very least, the General Assembly should first study the complexities and potential pitfalls of a regional minimum wage before implementing an approach that would leave so many workers behind.

Category:

Economic Opportunity