May 2, 2019

Arkansas’ Experience Suggests Greater Health Coverage Loss Than Anticipated if Virginia Moves Forward with Work and Cost Requirements

Work and cost requirements have not yet been approved for Virginia, and would take around one year to be put in place. While we continue to lift up the harms that work requirements would have on people in Virginia, we encourage those who think they may be eligible for Medicaid coverage to learn more at coverva.org.

One of the primary purposes of the Medicaid program is to give individuals and families with low incomes an opportunity to access affordable and quality health coverage. This past January, Virginia sought approval from the federal government to implement work reporting and cost requirements on parts of its Medicaid population, and a recent report found that the Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS) expects approval at some point this summer. Unfortunately, the proposed implementation of work and cost requirements puts thousands at risk of losing much-needed coverage. Recent court decisions put a stop to work requirements in Arkansas and continued to halt their implementation in Kentucky, adding further doubt as to the legality of these types of policies. While Virginia should take that into consideration, the state should also be wary of the policy based on other states’ experiences and projections. Data gathered in Arkansas prior to the court decision and new estimates find work requirements have and will lead to large numbers of people losing coverage and will have a chilling effect on re-enrollment. In addition, there is no strong evidence that work requirements have improved employment outcomes for the targeted group in Arkansas.

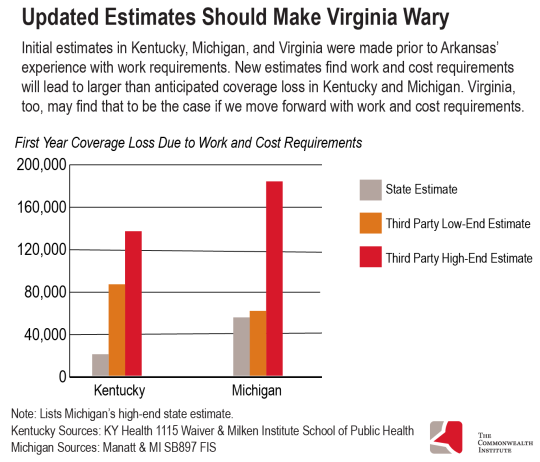

Arkansas, the first state to implement work reporting requirements for Medicaid recipients, saw 18,164 people – 23 percent of those subject to the new policy – lose coverage in 2018. Based on this experience, recent third-party estimates for coverage loss in Kentucky and Michigan, two states that have applied and received approval for work and cost requirements but have not yet implemented them, show higher numbers of expected coverage loss than initial state estimates.

In 2016, Kentucky estimated that 95,000 of its residents would lose health coverage by the fifth year of implementation as a result of work and cost requirements being tied to the Medicaid program with about 20,000 people losing coverage in the first year. However, recent analysis from George Washington University, which used a model based on Arkansas’ experience, estimates that between 86,000 and 136,000 people (26 to 41 percent of those subject to the requirement) would lose coverage within just the first year of implementation.

Prior to Arkansas’ experience with work requirements, the state of Michigan estimated a coverage loss of 4 to 8 percent of the total Medicaid expansion population. Michigan did note, however, that without actual experience from other states, the data was insufficient to provide a more precise impact. A recent publication from Manatt, which took Arkansas’ experience into consideration, found that an estimated 61,000 to 183,000 people—between 9 and 27 percent of the state’s Medicaid expansion population—would lose coverage in Michigan over a one-year period. The high-end estimate of loss is in line with the Arkansas experience, but even the low estimate indicates that more people could lose coverage than the state initially projected.

Virginia’s application to implement work reporting and cost requirements includes DMAS’s estimate that more than 25,600 people in the expansion population would lose Medicaid coverage within the first year of full implementation. That is roughly 8.5 percent of all adults the state initially expected to enroll by the time work requirements might likely kick in.

There are two factors that will likely lead to larger than projected coverage loss in Virginia. Medicaid enrollment has exceeded expectations, meaning more people will likely be subject to the reporting and cost requirements. Recent DMAS estimates put likely expansion enrollment in January 2020 at 363,500, while their original estimate was around 302,000. Using the same percentage of assumed coverage loss previously used by the state (8.5 percent), at least 31,000 people would be kicked off the program – 5,000 more than previously estimated for the expansion population in the first full year of implementation. This estimate does not include coverage loss for those who would be subject to work requirements but were enrolled in Medicaid before expansion. The state estimate for coverage loss for this population stands at around 1,150 people.

The second factor here is that, like Kentucky and Michigan, the number of people who could lose health coverage in Virginia was projected prior to any state having implemented the requirements (Virginia’s estimates mostly rely on calculations from February 2018, while Arkansas began implementing its requirements later that year in June). Incorporating the real world experience of Arkansas is a vital step toward understanding the impact of work requirements in Virginia. Based on the Arkansas experience and updated Kentucky and Michigan estimates, we can expect further losses than the 8.5 percent baseline originally anticipated in Virginia. The growing number of people likely to lose access to coverage in Virginia is troubling.

People who lost Medicaid coverage in Arkansas have not quickly sought coverage again. The Arkansas work reporting requirements reset every January, meaning those who lost coverage in 2018 could sign up again in 2019. However, these policies have had a massive chilling effect and close to 90 percent of the people who lost coverage in 2018 have not signed up again as of February of this year.

While some federal officials have argued that such low re-enrollment means that many who lost health coverage through Medicaid must have found jobs, there is no data to support those claims. Of the 18,164 beneficiaries who lost coverage in 2018 for not complying with the work requirement in Arkansas, only 1,981 had matches in the state’s New Hire Database. That means that for the more than 16,000 others who lost coverage, there is no evidence that they found new work. These factors suggest that much of the population that lost coverage continues to be underemployed, unemployed, or unable to work and are now also uninsured, effectively leaving them worse off than before the work requirements were imposed.

It is clear that Virginia is currently moving forward with a program it does not fully understand the consequences of. New information – data from Arkansas and higher than expected enrollment – is now available and the state should apply these findings to its coverage loss estimates and share them publicly. Anyone losing health coverage due to barriers set up by the state is too many, and these grim outcomes do not need to be part of Virginia’s future. There is still an opportunity to do away with these proposed requirements through state legislative action and refocus Virginia’s Medicaid program on its core objectives – delivering health coverage to low-income Virginians, and in turn, building healthy and thriving families and communities.

Category:

Health Care