March 1, 2023

Don’t Repeat Virginia’s History of Divesting from Public Schools

Every student, regardless of their background, should have access to a high-quality education that will help them reach their potential. Research conclusively shows funding has a major impact on student success. After years of underfunding, the state is now in a financial position to fully fund our schools, and lawmakers could choose to do so in a way that makes sure every student in every zip code has the resources they need to be successful. Unfortunately, some of these valuable public resources are in danger of being diverted to private schools, entities that can pick and choose which students to accept to their programs, rather than being invested in creating great public schools that are the bedrock of a strong multiracial democracy. To make matters worse, research shows that these private-school subsidies do not improve — and often worsen — student outcomes while fostering segregation and harming vulnerable students.

The fight for high-quality educational opportunities for every student is not new. As James Anderson notes in his seminal study The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, “…a central theme in the history of the education of Black Americans is the persistent struggle to fashion a system of formal education.” It is critical that today’s policymakers move us forward, not backward.

History of Segregation and Creation of Vouchers

Despite the benefits of racially diverse learning environments for students, Virginia has a long history of passing both overt and covert racist state policies to segregate schools and deprive communities of color of educational opportunities and resources. Prior to the Reconstruction period, education in Virginia was mostly reserved for wealthy white families. At the end of the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau created the first state-wide school system for African-Americans, but its operations ceased in 1869. In a positive development that same year, however, the new Virginia constitution included an amendment requiring a state-wide public education system. Furthermore, Virginia’s re-entry to the Union was conditional on the basis that the state provides free education to all students regardless of race. Over the next several decades, Black and white Virginians worked to make this promise real, yet Virginia legislators continued enacting policies to deny a high-quality public education for Black students. In the mid-20th century, this included the use of subsidies for certain (white) students to attend private schools, in some cases even closing public schools and denying Black students an education altogether.

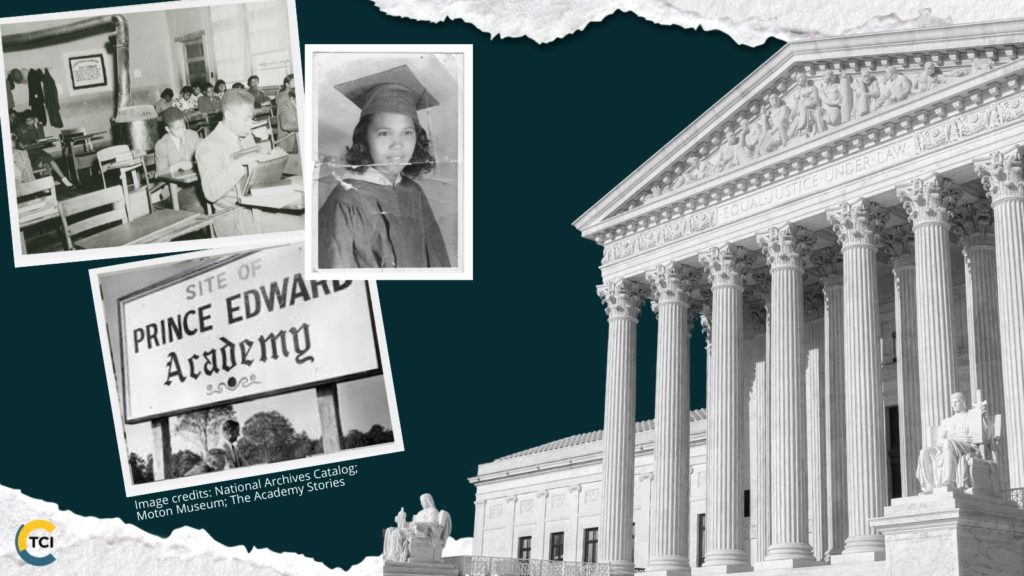

Virginia became a battleground for the fight against school segregation when Barbara Rose Johns organized the student body of Moton High School in Prince Edward County and led a walkout in protest of the conditions — overcrowded, under-resourced, and segregated schools. In response to court-ordered desegregation, Virginia policymakers passed a group of laws and political strategy, including closing schools rather than integrating, that became known as “massive resistance.”

Pupil placement boards were created to assign specific students to specific schools. Tuition grants, or vouchers, were given to any white student who found themselves in an integrated school, in order to attend private schools or a public school in a nearby locality, while public schools were closed. And the creation of private academies with a range of public subsidies, also known as segregation academies, was yet another tactic to circumvent the legal orders to desegregate. This lasted until the late 1970s when, similar to Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that private schools could not discriminate on the basis of race. Many of these academies still exist as private schools in Virginia and struggle with increasing the diversity of their student bodies. Meanwhile, Virginia public schools that serve many Black students continue to be underfunded, denying true access to an equal education.

Dangers of Fund Diversion

Given Virginia’s history of using private school subsidies to resist racial desegregation, and the research findings that private-school subsidies do not improve educational outcomes while harming vulnerable students, state and local leaders should be skeptical of proposals that seek to redirect funds for public education to private schools through private school vouchers or educational savings accounts.

There is little evidence that private school vouchers improve student achievement, with a large portion of the most rigorous studies finding no statistically significant effect for participating students and some recent studies with strong research designs finding that these programs harm student achievement. This includes studies finding that neo-voucher programs in Louisiana resulted in lower language arts and math test scores on standardized tests mandated by the state for accountability purposes for the low-income students who enrolled in private schools, including one that summarized their findings by saying, “participation substantially reduces academic achievement: attendance at an LSP-eligible private school lowers math scores by 0.4 standard deviations and increases the likelihood of a failing math score by 50 percent. Voucher effects for reading, science and social studies are also negative and large.” Similarly, a study of a voucher program in Indiana found that, “voucher students experienced an average achievement loss of 0.15 [standard deviations] in mathematics during their first year of attending a private school compared with matched students who remained in a public school. This loss persisted regardless of the length of time spent in a private school. In English/Language Arts, the study did not observe statistically meaningful effects.”

Furthermore, the discriminatory beginnings of vouchers are still felt today. While public schools are bound by federal and state laws to accommodate the needs of all students, private schools who receive public funding through vouchers are not. In fact, the proposed voucher legislation this year specifically states that, “An education service provider shall not be required to alter its creed, practices, admissions policy, or curriculum to accept payments.” This leaves students, including those with disabilities, LGBTQ+ students, students who are not fully proficient in English and need additional services (English learners), and religious minority students, in vulnerable and harmful situations.

Private school vouchers and educational savings accounts can be particularly harmful if they are designed in ways that exclude students from low-income families. For example, in many programs, the dollar value of the voucher falls far below most private school tuition costs, and when factoring in additional costs like transportation and uniforms, it effectively excludes students from low-income families. At the same time, not all programs target funds to students from low-income families or with special education needs. The result is a public subsidy to families who can already afford the majority of private school costs at the exclusion of those who can’t.

Meanwhile, using state dollars — whether in the form of tax credits or vouchers (so-called educational savings accounts) — for private schools leaves fewer available for public school students. And to the extent that these programs encourage parents to not enroll their students in local public schools, the resulting reduction in average daily membership directly reduces state funding for the local public schools. That’s a recipe for making the challenges of schools that already have inadequate resources worse, not better.

Virginia’s Board of Education has provided a list of research-based investments that would provide a higher-quality education for Virginia students, yet Virginia policymakers have not yet fully funded these priorities. Meanwhile, research also shows that students who participate in voucher programs have lower test scores than similar students who do not, and that fund diversion places a heavy strain on local school district resources and leads to harmful effects on students. These impacts are felt most acutely in communities that are low-income, rural, and/or predominantly people of color. Virginia policymakers should invest in what we know works to create great public schools in every community and should reject echoes of the past in diverting public dollars to private schools.

Categories:

Budget & Revenue, Education