January 8, 2024

How Does Virginia’s State Budget Work?

Originally published July 12, 2023: Updated Jan 8, 2024

Why the budget matters

Creating broadly shared opportunity requires investing our resources in the building blocks of thriving communities, such as education and health. That’s why the state budget is a critical tool to meaningfully dismantle barriers for people of color and families with low incomes across the state.

How big is Virginia’s budget? Where does the money come from?

For the budget year that started July 1, 2023 (fiscal year 2024), Virginia’s total state budget is $80.8 billion. Most of that ($51 billion, which is 63% of the total) is what’s known as the non-general fund budget, which includes federal grants for things like health care, gas taxes earmarked for transportation, and tuition payments from students at our public colleges and universities. The part of the budget over which legislators have the most flexibility, the general fund budget, is $30 billion for the fiscal year that started July 1. That general fund budget is funded mostly through individual income taxes plus the sales tax. Corporate income tax revenue is smaller as a share of state income tax revenue than in the past. Virginia’s corporate income tax provided 15% of Virginia’s income tax revenue in 1980 compared to just 10% last year.

How does Virginia’s state budget process work?

Virginia has a two-year budget process.

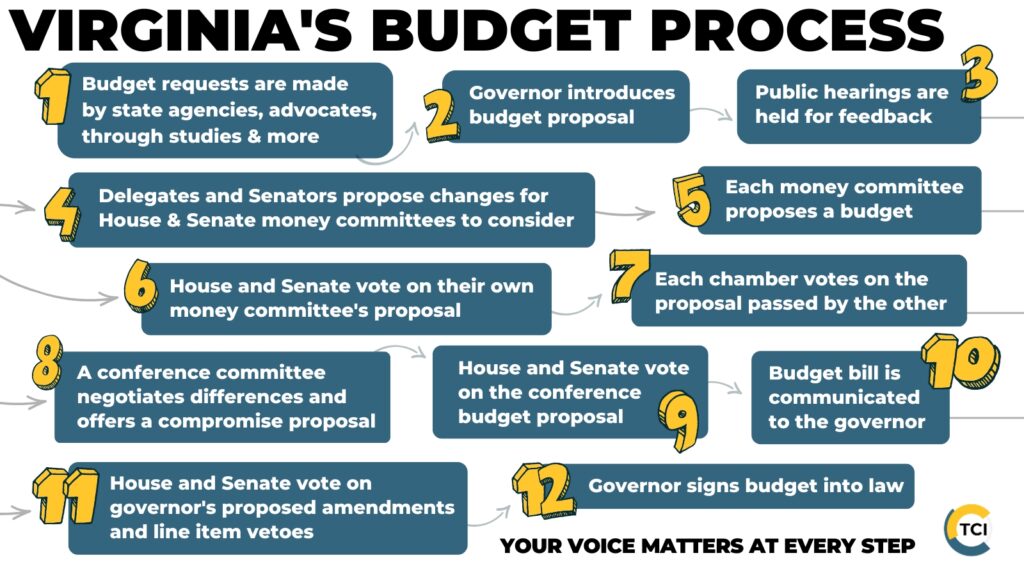

Each December, the governor introduces a budget proposal. For even-numbered legislative years, such as this year, the governor proposes a budget for the upcoming two fiscal years and changes to the current-year budget, and for odd-numbered legislative years, it’s a set of proposed amendments to the current two-year budget. On December 20, 2023, ahead of the 2024 session, Governor Youngkin proposed a new two-year budget that will cover the fiscal year that starts July 1, 2024, and the next one that starts July 1, 2025, as well as changes to the current fiscal year budget (which started July 1, 2023).

Next, during the legislative session, the House and Senate each propose amendments to the governor’s proposal. After each legislative chamber rejects the other’s proposal, the House and Senate appoint “conferees” who negotiate a deal and present a “conference report” that the House and Senate then approve.

Then, the governor has the opportunity to propose amendments and line-item vetoes to the budget, which the legislature then votes to approve or reject. The governor’s budget amendments must be approved by a simple majority of each chamber to succeed. Line-item vetoes can only be overridden by a two-thirds supermajority in both chambers. There are constitutional limits to the Governor’s line-item veto power. If everything runs on time, the legislature votes on the governor’s proposed amendments and line-item vetoes during the “reconvened” session on the sixth (or seventh) Wednesday after the end of the regular session.

Category:

Budget & Revenue