June 8, 2016

Making A Fair Comparison When Looking at School Spending

Richmond is not Chesterfield.

And Petersburg is not Prince George, Hampton is not Poquoson, and Charlottesville is not Albemarle. While they share borders, the differences between these cities and nearby suburbs are quite noticeable in terms of poverty rates and the racial mix of their residents, and the same is also true of their local schools. Because of their differences in poverty, suburban school divisions should not be the comparison point for city schools when gauging the efficiency and effectiveness of school spending as some observers have been doing.

These differences are important because students from families that struggle to get by require additional services and supports that students from more affluent families may not require. These services can include early childhood learning programs so students enter kindergarten with basic skills, providing additional instruction and remediation to help struggling students, and adequate compensation to attract and retain the best teachers, which can be more costly in schools with high concentrations of students from poor families.

And all this costs money.

In fact, it can cost two to two-and-a-half times as much to help low-income students achieve academic success because of the barriers they face through no fault of their own. In a state-commissioned review, a team of experts in Maryland found that it cost over twice as much to educate low-income students. Following that review, the state adjusted its aid formula to reflect the reality of these higher costs.

This means schools in communities with higher levels of poverty should have higher levels of spending to give their students similar academic opportunities. Recent evaluations find that added investments from states in low-income school divisions help improve test scores, graduation rates, and even adult earnings.

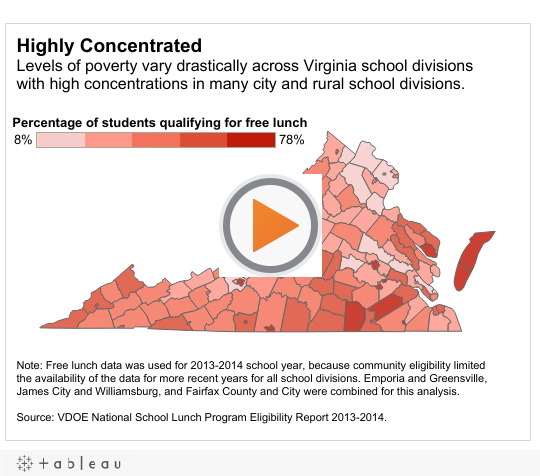

In Virginia, the percentage of students receiving free lunch – the measure the state uses for the number of academically at-risk students – varies dramatically when comparing cities to their suburban neighbors. In Richmond City, the percentage is at least twice as large as the surrounding counties of Chesterfield and Henrico. In Petersburg, it’s over two-and-half times as large as Prince George and Chesterfield.

The same is true in other areas of the state: In Hampton and Newport News, the percentage of students qualifying for free lunch is over three times more than in neighboring Poquoson and York; And the same is true when comparing Roanoke City to Roanoke County.

To put these numbers into context, if Chesterfield had the same percentage of low-income students as Richmond City and had to spend twice as much to support the education of these students, as studies have shown is needed, then total per student costs there would have been about the same as Richmond City’s in 2015 – and that doesn’t take into to account other differences in their school populations, like the number of English Language Learners and students with disabilities.

Per student spending would have been greater in Prince George if it had the same percentage of low-income students as Petersburg. And the same would be true for Poquoson and Hampton, Roanoke County and City, and Virginia Beach and Norfolk, among others.

As the public and media hold their local schools accountable, we cannot ignore that different students have different costs associated with their education. The evidence is very clear that students from low-income families have substantially greater needs and require additional resources. Failing to provide adequate resources presents a false choice to schools: cut services for the general student body or ignore the specialized needs of low-income students.

That is not a choice we should have to make.

Category:

Education