June 29, 2022

Mixed Bag: State Budget for Upcoming Two Years Has Important Improvements & Setbacks for Racial Justice

Virginia families deserve a budget that helps them make ends meet and invests in the future. The budget for the upcoming two years makes important steps in that direction, but also includes some significant setbacks.

Positive changes include major improvements to Virginia’s Earned Income Tax Credit, which provides targeted relief to thousands of families in Virginia who are living paycheck to paycheck, and increased investments in public schools.

Unfortunately, the budget also includes significantly larger tax changes that are not well-targeted to help the families who are struggling the most and, without a plan to replace the lost revenue, weaken our ability to meet the needs of all Virginia communities. Additionally, the budget includes several harmful changes that undermine recently-passed legislation and target communities with little access to political power. These are divisive choices that should not be continued in the future.

This summary outlines the major policy and budget decisions made through the 2022 budget process, with a focus on the compromise budget that the legislature passed on June 1 and the outcomes from the governor’s proposed amendments to that compromise budget.

Jump to:

Tax Policy

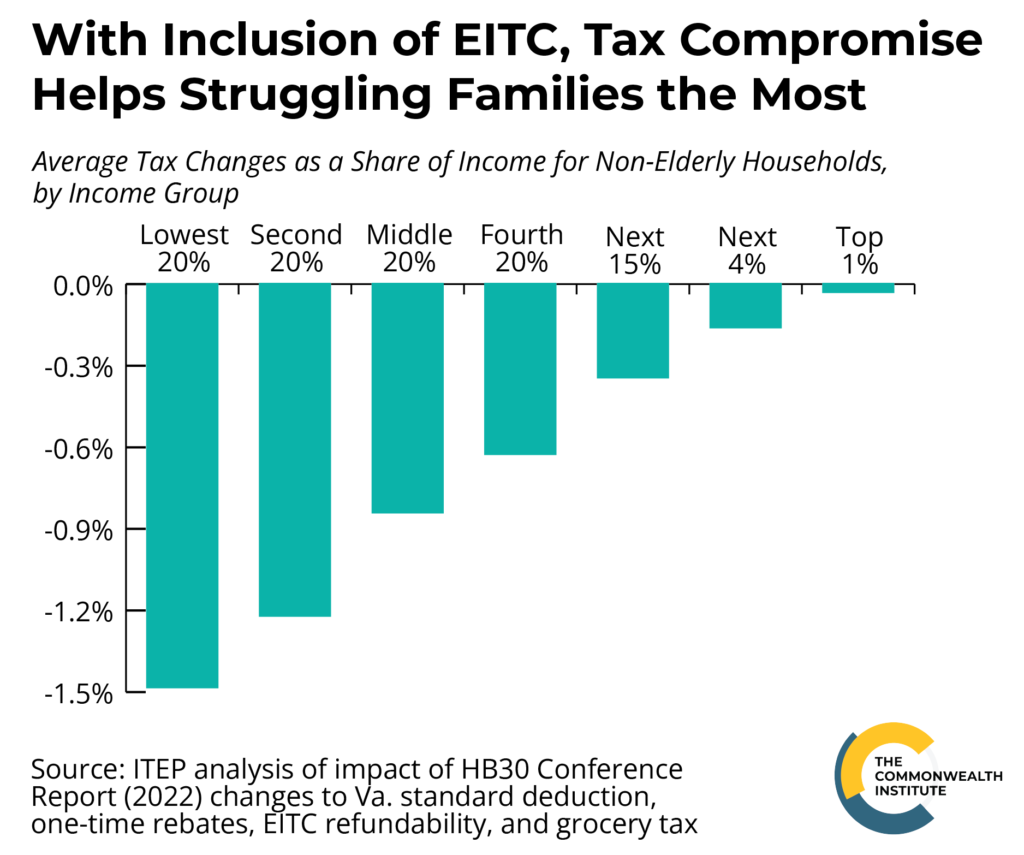

Despite underinvestment in public education and other key services, the faster-than-expected rebounding of revenue following the COVID-19 recession focused the 2022 budget process on tax cuts. The budget for the upcoming two years, which lawmakers passed on June 17 and the governor signed on June 22, includes a range of tax cuts. Some are targeted to helping low-income families while avoiding a depletion of funding for local governments in Virginia, yet others reduce shared resources at the state level that could have been invested in our communities.

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): The final budget improves Virginia’s EITC by making it partially refundable, which helps to increase incomes for working families across the state, particularly Black and Latinx families, and reduce long-standing wage gaps that persist for Black and Latinx working people. Previously, Virginia had a nonrefundable state EITC, which caps the amount of the credit available to families. Making Virginia’s EITC refundable was a critical improvement to make sure that lower-income working families were not left out of the income tax changes this legislative session.

- The conference budget that passed the General Assembly on June 1 included a partially refundable EITC equal to 15% of the federal EITC.

- The governor did not amend the improvements to the EITC that were included in the conference budget. This means the improvements will become law.

- Standard deduction: The most significant cut to state revenue in the final budget is from the increase in the standard deduction, which is used by tax filers who claim the federal standard deduction rather than itemize their deductions. Because many tax filers with lower incomes can reduce their state income taxes through existing tax provisions and credits, increasing the deduction leaves out many of the lowest-income families — improvements to the EITC helped make sure these families were not left out of the complete tax package. The increase to the standard deduction provides the most help to tax filers with incomes between about $24,000 and $76,000, as well as non-elderly and non-disabled individuals with somewhat lower incomes who do not claim dependents. However, the reduction in future revenue from the standard deduction changes may undermine Virginia’s capacity to invest in public education, transportation, and other critical services that build opportunity.

- The compromise budget increased the deduction to $8,000 for individuals and $16,000 for couples. This will reduce state revenue by $1.6 billion over the upcoming two years. With another recession potentially looming, legislators included language to limit the increase to $7,500 and $15,000 if revenue growth targets are not met. Lawmakers had already increased the standard deduction during the 2019 General Assembly session by 50% to $4,500 for an individual and $9,000 for a married couple filing jointly.

- The governor did not amend the changes to the standard deduction that were included in the conference budget. This means the changes will become law.

- One-time tax rebates: The compromise budget included one-time income tax rebates. Although these rebates do not limit future revenue, and therefore do not pose as high a risk as the standard deduction changes to future funding for core services, like the standard deduction change they exclude many families and individuals with lower incomes. Similar, though smaller, rebate checks were issued in 2019 and excluded over 1 million — about 3 in 10 — tax filers in the state. Although millionaires in the state would receive full rebate checks under the proposal, many other tax filers will receive much smaller amounts than the maximum amounts.

- The compromise budget included one-time tax rebates of up to $250 per individual or up to $500 per married couple (estimated budget impact $1.0 billion).

- The governor did not amend the changes to the rebates that were included in the conference budget. This means the changes will become law.

- Gas Tax: Governor Youngkin proposed an amendment to the legislature’s compromise budget to temporarily suspend Virginia’s gas tax and permanently limit future updates to gas tax rates, hurting Virginia’s ability to maintain and improve our system of roads and public transportation. This budget amendment would have cost Virginia about $437 million over the next two years while doing little for Virginia families compared to other tax policy options. As was made public in recent congressional testimony by oil industry executives, gas prices are set by global markets and demand for oil, not by state and federal taxes. As a result, about 30% of savings from this proposal would have been captured by the oil industry, with another 24% going to people who live outside of Virginia.

- The conference budget did not include any changes to Virginia’s gas tax.

- As with a similar proposal this spring, the Senate rejected that amendment in order to protect critical funding for transportation and focus tax cuts where Virginia families would directly benefit.

- Grocery tax: Households with low and moderate incomes pay a larger share of their income toward sales taxes because a larger portion of their income is spent on consumer goods, like food and personal hygiene products. At the same time, sales taxes are an important funding source for state and local budgets. Virginia’s 1.5% state sales tax on groceries is dedicated to K-12 education and transportation, while there is also a 1% local sales tax option that is available to local governments.

- The legislature’s compromise budget eliminated the 1.5% state sales tax that applies to groceries and personal hygiene products (eff. Jan. 1, 2023), while leaving in place the 1% local sales tax option that exists for localities. The budget replaces revenue for local school divisions based on school-age population.

- The governor did not amend the change to the grocery tax that was included in the conference budget. This means the change will become law.

K-12 Education

The budget for the upcoming two years makes several overdue improvements in funding for public schools, including the state share of salary increases, support for school divisions with high poverty rates, improvements to school infrastructure, and funding to increase support staff positions. However, the budget does not include much-needed additional support for English Learners, and Virginia’s overall support for public education still falls short of what the Board of Education has stated is needed to provide a high-quality education for every student.

- Teacher and staff pay: Effective teachers are the most important school-based factor for student educational performance and teacher pay is an important tool for attracting and retaining teachers. Virginia’s average teacher pay was more than 10% below the national average in 2020 despite Virginia being a top-10 state for median household income and a relatively high-cost state. And a recent national survey found 1 in 4 teachers were considering leaving their job by the end of the school year, with Black teachers particularly likely to be considering leaving.

- The compromise budget provided the state share of a 5% increase in pay each year for teachers and other school staff ($730 million over the biennium). The legislature also provided $125 million of federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding to pay for a $1,000 bonus (no local match required) for teachers and staff in December.

- The governor did not amend the funding for teacher and school staff pay beyond technical fixes to the bonus calculation. This means the change will become law.

- At-Risk Add-On: School divisions that are located in rural areas, have a majority of students of color, or are in communities with a high share of poverty often have less resources to invest in schools, leading to less resources for students. Research shows that increased investments in schools have profound impacts on student outcomes, from graduation rates to academic improvements.

- The compromise budget provided $145 million for the At-Risk Add-On, a state program that provides additional funding to divisions based on the share of their students living in poverty. This is less than was proposed by former Gov. Northam in his outgoing budget proposal, yet is still an important step forward.

- The governor did not amend the funding for the At-Risk Add-On program. This means the change will become law.

- English Learner teachers: Insufficient staffing and resources have clear consequences for students who are learning English (EL students), most of whom are Latinx, as seen in SOL pass rates and on-time graduation rates. Currently, the state funds 20 EL instructional positions for every 1,000 students. The Board of Education has stated that Virginia needs to both increase its overall support for English learners and move to a tiered system and provide the most help for students with the lowest levels of English proficiency.

- Legislators rejected a proposal from former Gov. Northam to increase the number of instructors to 22 for every 1,000 English learners, instead maintaining the current ratio of 20 positions for every 1,000 students.

- The governor did not amend funding for English learners. This means the budget does not include any improvement in the state’s ratio of instructors to English learners.

- Support cap: This arbitrary cap was imposed to save money during the Great Recession, cutting hundreds of millions in state funding ever since for school support staff, including social workers, custodians, and food service staff. Between 2009 and 2020, support staff decreased by 1,700 positions across the state, while student enrollment increased by 63,000 students.

- The compromise budget partially removed the cap, providing nearly $272 million to increase support staff positions.

- The governor did not amend the funding for the support cap. This means the change will become law.

- Principals and assistant principals: Virginia’s Board of Education recently reaffirmed its 2016 recommendation that the Virginia Standards of Quality for K-12 schools include one full-time assistant principal for every 400 students and one full-time principal for every elementary school. When Virginia’s legislature and state budget do not fully recognize the Standards of Quality as prescribed by the Board, it means less state funding to K-12 schools. Some school divisions can make up the difference. But school divisions in areas with fewer local resources, including low-income rural and urban school divisions, aren’t able to do so, resulting in fewer opportunities for students in high-poverty schools.

- The compromise budget provided $20 million to cover the state share of one full-time principal for every elementary school, but did not provide additional funding for assistant principals.

- The governor did not amend the funding for principals and assistant principals. This means the change in funding for principals will become law.

- School construction: With the zeroing out of most state support for school infrastructure over the past decade, Virginia school divisions have an increasingly large backlog of needed upgrades. This harms Virginia students: there is clear evidence that having modern school infrastructure directly improves student outcomes, the health of students and staff, and teacher retention.

- The conference budget included several approaches to supporting school construction and modernization. First, the budget provides one-time grants for non-recurring costs related to school construction, renovations, and other expenditures in the amount of $800 million. Roughly half of the funding will be distributed via a competitive school construction fund, with the remainder allocated to school divisions. In addition, the conference budget transfers $50 million of Literary Funds to school construction grants and clarifies that up to $400 million in additional Literary Funds over the biennium may be used for school construction loans.

- The governor did not amend the funding for school infrastructure. This means the improvement will become law.

- Lab schools: The state has a constitutional responsibility to support a high-quality public education for every student in every district. With Virginia’s legislature still not meeting the funding standards that Virginia’s Board of Education states is needed to do that, the best use of available money is to invest in public schools in order to meet the state’s commitment to a high-quality public education. Experimental lab schools do not help Virginia achieve this basic goal, particularly when the funding is diverted to private institutions that may not fairly serve every Virginia student. (Language in this section was updated July 2022 to reflect the chapter budget.)

- The compromise budget included $100 million in one-time funding for start-up costs and per-student costs at “lab schools” run by public baccalaureate colleges and universities.

- Gov. Youngkin proposed two changes to the lab schools proposal: allowing private colleges to establish lab schools and shifting funding from local school divisions to lab schools. The legislature accepted the amendment to allow private colleges and universities, such as Liberty University, to open lab schools. This change does not appear to apply to the $100 million lab school fund.

Higher Education

- Tuition and financial aid: For students who are Black, Latinx, and/or from families with low incomes, financial aid plays a crucial role in the ability to attend college. In 2018, the average net cost of attendance at a public four-year university in Virginia accounted for 36% of median household income for Black families and 27% for Latinx families, while it only accounted for about 23% of median household income for non-Hispanic white families and 17% for Asian American families.

- The legislature’s compromise budget included $246 million in additional flexible affordable access funds and $140 million in need-based undergraduate financial aid. The compromise budget also included $5 million each year to help Virginia’s public colleges and universities meet additional financial aid need for immigrant students newly eligible under Virginia’s 2021 financial aid equity law.

- The governor proposed and the legislature accepted an amendment to remove the additional funding that would have helped make sure public colleges and universities have enough financial aid to meet the needs of every eligible student, including newly eligible immigrant students, many of whom are students of color. Although this does not impact the eligibility of students for financial aid, some colleges may find it more difficult to meet financial aid needs of all their students.

- HBCU investments: Virginia’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) play an important role in helping low-income, first-generation students find new opportunities. Yet HBCUs are historically underfunded in Virginia.

- The conference budget included $90.9 million across the biennium in additional operating support for Virginia’s public and private HBCUs. That included $20 million for Norfolk State University and $20 million for Virginia State University in extra affordable access funds and an additional $31 million for programs and services at the universities. The budget also included $20 million for scholarships at Virginia’s two private HBCUs, Virginia Union University and Hampton University, and an additional $9 million for $5,000 supplemental Tuition Assistance Grants (TAG) for students attending those private universities.

- Gov. Youngkin proposed and the legislature accepted several amendments to increase funding for public and private HBCUs, including $2 million for Virginia Union University (via the City of Richmond) for an innovation center and further increases to supplemental Tuition Assistance Grants and financial aid for HBCUs. Unfortunately, despite significant available resources in the budget and no other amendment having an embedded pay-for — the governor tied the further increases to financial aid and TAG supplements to the removal of financial aid funding to serve newly eligible immigrant students. As the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus noted before the vote, this choice “pit[s] communities of color against one another and perpetuates a false scarcity problem. Both items can and should be funded.”

Health Care

- Medicaid dental reimbursement rates: A robust oral health provider network is vital to make sure that families who access health care through Medicaid or FAMIS can make timely appointments with local dental providers. Due to historical and modern day barriers to affordable and comprehensive health coverage, Black and Latinx people living in Virginia are less likely to have health insurance. Lack of coverage contributes to Black and Latinx people being less likely to have visited a dentist or dental clinic within the last year compared to the state average.

- To incentivize more dental providers to participate in Virginia’s Medicaid program, the compromise budget included a 30% increase in dental service reimbursement starting on July 1, 2022 (fiscal year 2023), with a budget impact of $84.8 million.

- The governor did not propose amendments to the Medicaid dental reimbursement funding. This means the improvement will become law.

- Medicaid enrollment as public health emergency unwinds: When the federal Public Health Emergency expires, all adults and children enrolled in Virginia’s Medicaid program will need to undergo eligibility redetermination for the first time since the start of the pandemic. Many things have changed for families over the past two years, including mailing addresses and contact information. This undertaking should be well-planned, well-resourced, and informed by people who are impacted and their advocates. Failure to do so could lead to a drastic, unnecessary loss of health coverage. Around 1 million people of color participate in Virginia’s Medicaid and FAMIS programs.

- The compromise budget included language to form a task force led by the Secretary of Health and Human Resources to help plan and advise the Department of Medical Assistance Services on the unwinding process. The language also gives authority to the workgroup to use federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds for these efforts. The “Task Force on Eligibility Redetermination” is expected to provide updates on their work to the governor and the House Appropriations and Senate Finance and Appropriations Committees by October 1, 2022, and every 90 days after through June 30, 2023.

- The governor did not propose amendments on the creation of the “Task Force on Eligibility Redetermination”. The budget language will become law.

- Cover All Kids study: Families with undocumented children have few avenues to sign up for affordable and comprehensive health coverage. Federal law prohibits these families from accessing coverage through Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace. These barriers to health coverage have led to troubling disparities in health coverage rates in Virginia. Children who are citizens have an uninsured rate of 4.1%, while an estimated 48% of non-citizen children with undocumented status in Virginia are uninsured.

- The Senate budget proposal included language directing the Joint Subcommittee for Health and Human Resources Oversight to evaluate options to establish a state-funded health coverage program for children under 19 years of age who are uninsured and would qualify for Medicaid or FAMIS except for their immigration status. The study would have also reviewed policy options to expand coverage for all uninsured children. No such study was included in the compromise budget.

- The governor did not propose amendments to the budget that would have studied this policy further, leaving 9,000 children uninsured with little to no options for affordable and comprehensive health coverage.

Housing

- Housing Trust Fund: A recent state study found that 300,000 renters in Virginia are cost-burdened, meaning they pay a higher share of their income toward housing costs than is generally considered affordable (30% of income), and that Black, Latinx, and senior households are more likely to be cost-burdened. Black and Latinx families are also most at risk of eviction and foreclosure. The Virginia Housing Trust Fund provides competitive, low-interest loans for the production and preservation of affordable rental and homebuyer housing and grants for reducing homelessness.

- The legislature’s compromise budget increased funding for the Virginia Housing Trust Fund by $20 million each budget year, for a total deposit of $75 million each year. This is substantially less than former Gov. Northam proposed, which was a total of $125 million in the upcoming year (fiscal year 2023) and $175 million the following year. The legislature’s budget also included language allowing money to be removed from the Housing Trust Fund if revenue losses from the housing opportunity tax credit exceed expectations.

- The governor did not propose amendments to the funding for the Housing Trust Fund, leaving it well below the funding levels that are needed to meet the needs of Virginia communities.

- Energy efficiency upgrades for low-income Virginians: Because families with low incomes and families of color often cannot afford to rent or buy energy-efficient homes, or pay to upgrade their existing homes to be more energy-efficient, many face high energy bills on top of already struggling to make ends meet. Data from before the pandemic showed that 2 out of every 3 low-income households faced a high energy burden, and Black, Latinx, Native American, and older adult households face particularly high energy costs compared to their incomes.

- The legislature’s compromise budget included $190 million of special funds from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) for the Housing Innovations in Energy Efficiency program, which funds upgrades to new and existing residential buildings to reduce bills for low-income Virginians. The legislature also included language allowing up to $11.4 million in energy efficiency funding to be reallocated to assist flood victims in Hurley, Virginia.

- The governor did not propose amendments to the energy efficiency funding.

- Virginia Housing Stability Fund: Due to federal funding constraints, only 1 in 5 eligible households in Virginia actually receives a federal housing voucher to subsidize their rent. As a result, 85% of extremely low-income renters in Virginia are cost-burdened and 71% of them are severely cost-burdened, which increases the risk of eviction, adversely impacts children’s ability to perform in school, and can negatively impact parents’ mental and physical health.

- The legislature’s budget created a stakeholder workgroup to develop model guidelines for a program to provide long-term rental assistance. The stakeholder workgroup would issue a report with recommendations by November 30, 2022.

- The governor did not propose amendments to this study.

- Housing tax credit: Last year, the General Assembly established the Virginia Housing Opportunity Tax Credit, which provides state tax credits for low-income building projects that receive federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs), with a $15 million annual cap on the state tax credits.

- The legislature’s compromise budget raised the annual cap on the Virginia Housing Opportunity Tax Credit to $60 million each year for fiscal years 2022 through 2025 from the current $15 million annual limit, and included language changes that shift the timing of revenue losses from the tax credits, resulting in short-term budget savings and longer-term costs. Additional language allows funding to be removed from the Virginia Housing Trust Fund if revenue losses from the tax credits exceed expectations.

- The governor did not propose amendments to this tax credit.

Criminal Legal System

In addition to both the legislature’s compromise budget and governor’s amendments including significant salary increases for a range of correctional and law enforcement – above and beyond those included for other state and state-supported local employees – both the legislature and governor used budget language to legislate changes to laws that had been debated and signed into law in recent years.

- Earned Sentence Credit: Earned sentence credits allow individuals who are incarcerated with eligible offenses to reduce the length of their sentence if they engage in specific programs and productive activities. Legislation passed in 2020 (HB 5148 & SB 5034) established an earned-sentence-credit structure, outlining eligible offenses and conditions under which an individual may qualify for the program. Since that time, hundreds of individuals have been working and preparing to be reunited with their families and communities ahead of their original release date.

- The governor proposed and the legislature accepted an amendment that limits the use of earned sentence credits for individuals who are incarcerated. The amendment reduces the number of eligible offenses to participate in the earned sentence credit program, effectively decreasing the number of individuals who were set for release under the original policy. Approximately 550 individuals who have been working for the past two years toward their release will remain incarcerated, disrupting the reunions of many families across the commonwealth.

- Presumption of Bail: The right to due process and a presumption of innocence are central to promoting fairness and justice within our criminal legal system. However, these principles were undermined by Virginia’s pre-trial practices in the past, which presumed that people charged with certain crimes did not qualify for bail. Defendants would have to “rebut” or prove that presumption false. Virginia legislators acted last year to reform Virginia’s pre-trial detention system by providing an opportunity for an individualized assessment of risk in the place of a number of presumptions against pre-trial release.

- Gov. Youngkin attempted to roll back that progress this year by trying to amend this law through the budget process. The amendment attempted to revert Virginia’s law to include rebuttals that were removed through legislative reform.

- Thankfully, the amendment was not approved by the legislature, and the law remains intact with the progress made in 2021. Reverting to the prior policy would have created significant economic harms for Virginia families and communities, as well as fiscal costs for the state and local governments.

- Marijuana Possession: While Black people and white people consume marijuana at comparable rates, police are 3.5 times more likely to arrest Black Virginians than white Virginians for marijuana possession. Once arrested, courts convict Black Virginians of a marijuana charge at a higher rate — 3.9 times higher than white people. In 2020 and 2021, legislators took steps toward racial justice — first through the decriminalization of simple possession of marijuana, and then through the legalization of marijuana possession of up to one ounce. Possession of over one ounce of marijuana was subject to a civil penalty of no more than $25. Possession of over one pound of marijuana was never decriminalized and remains a felony offense.

- Through the budget process, the Virginia General Assembly voted to recriminalize possession of between four ounces and one pound of marijuana. An individual in possession of four ounces to one pound of marijuana may now be charged with a Class 3 misdemeanor for a first offense, and a Class 2 misdemeanor for a second offense. This re-criminalization of marijuana is a step backward in goals toward racial justice.

Categories:

Budget & Revenue, Decriminalizing Poverty, Economic Opportunity, Education, Health Care, Immigration