August 3, 2020

State Lawmakers Have Tax Policy Options to Meet the Moment and Lay Groundwork for Stronger Recovery

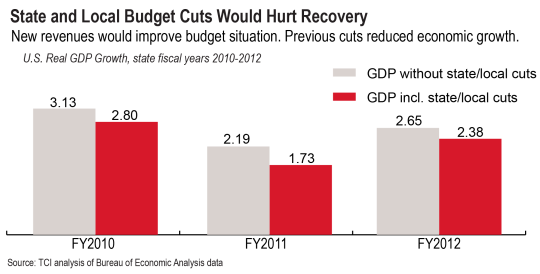

Virginia has pressing budget challenges, even as the state is providing additional public services necessary to respond to the COVID-19 health crisis and the economic hardship that has resulted. Pulling back on state services would almost certainly worsen the downturn and slow any recovery. The state will need to generate new revenues to meet this moment and the years ahead, particularly once emergency federal aid winds down. Virginia lawmakers should consider a combination of tax policy reforms that would reduce the need for state budget cuts while also putting the state on stronger footing in the long term. By taking an approach that includes new revenues, state leaders can meet the many health care and education needs across the commonwealth and drive the economy towards recovery.

State lawmakers will return to Richmond on August 18 for a special session to consider budget actions and policy changes related to policing and criminal justice. Governor Northam recently announced that final state revenue collections for the state fiscal year that ended on June 30 show a shortfall of $236.5 million relative to the official revenue forecast. Although this preliminary figure is better than initial estimates, large revenue shortfalls are still expected over the next two years.

In recent years, the General Assembly has adopted important reforms to the state revenue system, like better aligning state sales tax requirements with the growth in online retail. However, the state tax system still needs structural reforms. For example, Virginia’s income tax brackets and corresponding rates remain unchanged since the 1987 state tax reform law that phased in a series of updates over several years. The state’s top individual income tax bracket begins at just above $17,000 in taxable income. In practice, Virginia’s income tax system resembles a flat tax, where about 60% of taxpayers pay the same marginal tax rate. In effect, many taxpayers with low or moderate incomes pay the same marginal rate as millionaires.

By adopting a much more progressive bracket and rate structure that would add a surcharge for tax filers with high incomes, the state revenue system would generate substantially more revenues, while leaving most taxpayers unaffected. A plan along these lines that applied surcharges of 0.75%, 1.75%, and 2.75% on incomes above $100,000, $500,000, and $1 million, respectively, could generate close to $1 billion per year. Alternatively, surcharges of 1%, 2%, and 3% at those income levels could generate close to $1.2 billion per year. This kind of policy change would ask households with more resources to chip in more and help the state make key investments for the years ahead.

Without a more progressive income tax, Virginia requires taxpayers with moderate incomes of all races to pay the same rate as those with the highest incomes, who tend to be white. To make up the difference, the state must either rely on regressive taxes, which disproportionately affect Black and Latinx taxpayers in the state, or make fewer investments in public services. State budget cuts and failures to invest often hit communities of color the hardest.

Lawmakers should also revisit two pieces of tax fairness legislation that were considered, but not adopted, during the 2020 General Assembly session:

- Enacting a corporate tax reform known as mandatory combined reporting that helps to counter common tax avoidance strategies of large, multi-state corporations

- Restoring Virginia’s estate tax on the wealthiest estates that would otherwise pass millions in assets and capital gains onto heirs without owing state tax

Because corporate taxes and estate taxes are largely taxes on wealth, these policies would likely also reduce racial inequality. Median wealth among white households is higher than Black and Latinx households. Historical and present-day barriers related to housing, education, employment, and other areas continue to contribute to the racial wealth divide. Inheritance and wealth are linked; for white households, their higher likelihood of receiving an inheritance and the larger average value of inheritances received may explain part of this divide. Adopting these policies to support public investments would help to build greater opportunity more broadly across the state.

In addition to more comprehensive reforms to the tax system, state policymakers can adopt technical fixes to close gaps in the tax code and limit existing tax breaks–similar to actions taken during the previous downturn.

Include digital products and services in the sales tax base (about $20 million annually)

The health crisis is accelerating the trend of economic activity shifting online. However, much of this new consumer spending is exempt from Virginia’s state and local taxes. Among states that have sales taxes, Virginia is one of only 16 states that generally does not apply that tax to digital products (as of Oct. 2019). By updating the tax code to include these products, the state would put them on a level playing field with equivalent goods that have been traditionally included in sales taxes and generate an estimated $20 million per year in needed state revenues, as well as new state and regional transportation and local revenues.

Eliminate remaining dealer discount program (about $13 million annually)

Virginia allows certain retailers to retain a portion of their sales tax collections. Before the last recession, this program had been much broader and had a larger revenue impact; since July 2010, the state has limited the program only to retailers that are not required to remit sales tax collections electronically. Fully eliminating this program–as proposed by the Kaine administration during the last downturn–would increase General Fund revenues by close to $13 million per year.

Decouple from Opportunity Zones break ($8 million to $9 million annually)

The federal Opportunity Zones program provides capital gains tax breaks for certain qualified investments in designated geographic areas. At the state level, Virginia conforms to this tax break, which means investors receive both federal and state tax breaks for their investment income. When the conformity law was under consideration, the Opportunity Zones provision had an estimated negative state revenue impact of $8.1 million to $9.0 million per year for FY 2020 through FY 2024.

The Opportunity Zones program has been criticized because of concerns that it will contribute to gentrification and displacement. Even if benefits of the program materialize, there is not a strong justification for Virginia to subsidize investments in Opportunity Zones with a state tax break because qualifying Virginia taxpayers can make those investments anywhere in the country.

Several months ago, the federal Joint Committee on Taxation revised its estimates of the program’s revenue impact upward by an additional 75% per year, so the budget impact on Virginia could be larger than previously estimated.

Restore cap on Land Preservation Tax Credit ($6.6 million annually)

In recent years, policymakers have placed limits around certain tax credits to minimize their budget impacts, including the Land Preservation Tax Credit. In this case, state lawmakers have made a policy choice to incentivize land preservation, but also routinely cap the maximum tax break that can be received in a given year. Between taxable year 2015 and when it expired earlier this year, the state has limited taxpayers to a maximum $20,000 per year for this credit. Restoring this cap would preserve about $6.6 million per year.

Conclusion

Important policy gains have been achieved in recent years, but many of these victories will require continued state investment. Less funding for important core services means moving backward. However, Virginia policymakers can chart a new course and avoid the same mistakes of previous recessions when budget cuts were enacted and never fully reversed, even years later. Although recent governors and legislators often did not look to new state revenues as part of a balanced approach to filling budget gaps, the current environment demands progressive action. Tax policy needs to be part of the solution.

Category:

Budget & Revenue