January 19, 2024

The 60 Year Shadow of Court Fines & Fees

Originally published Jan 10, 2022; Updated Jan 19, 2024

Virginia’s criminal legal system should advance justice, treat people fairly, and promote rehabilitation. Yet in Virginia, and across the country, court-imposed fines and fees create poverty traps and erode trust in the judicial system. Even for the most minor offenses, fines and fees can transform into major financial burdens. This is particularly true for people who are unable to pay their debts upfront, as they often face additional fees, high interest rates on the debt, and even wage garnishments. At the same time, these burdens are not equally shared: TCI’s prior research has demonstrated that fines and fees are imposed with unparalleled intensity in Black communities — a result of the racial biases in the criminal legal system. This legislative session, policymakers should seize every opportunity to support new legislation to reform Virginia’s system of fines and fees.

In 2021, a broad coalition of advocates engaged lawmakers and were able to repeal some of the most onerous debt collection practices, specifically involving court fines and fees. House Bill 1895 (2021) extended the grace period on interest that accumulates on court debt from 40 days to 180 days and made payment plans universally available, rather than limiting them to people who can afford a down payment. Yet state lawmakers must pass further policy reforms in order to decriminalize poverty and ensure everyone — no matter their race or wealth — has a fair chance to thrive.

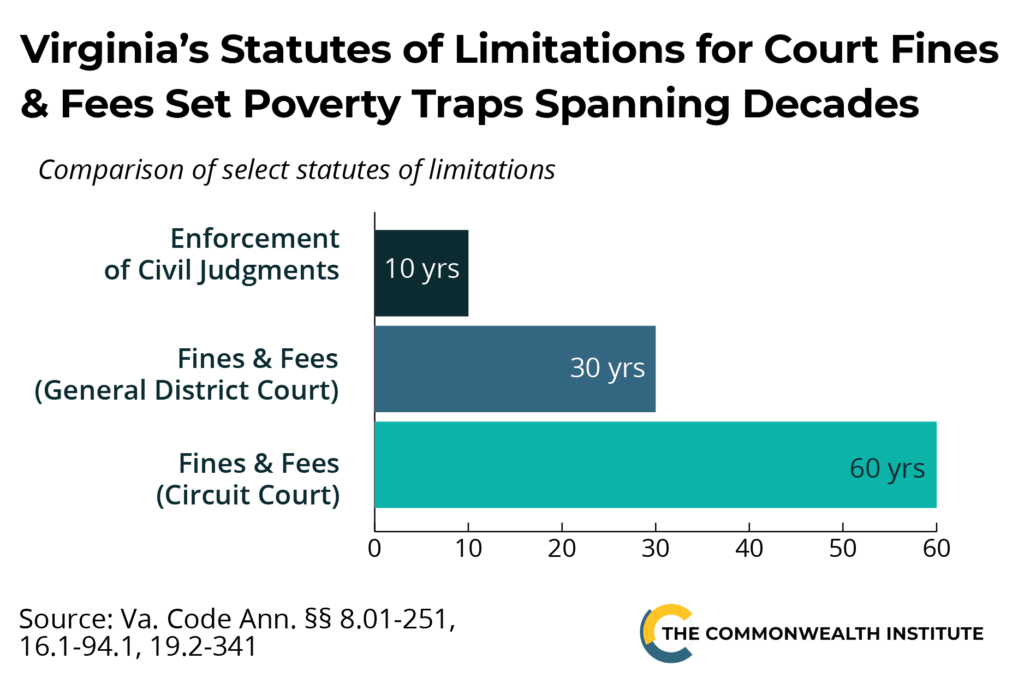

One of the reasons why court fines and fees function as poverty traps for so many Virginians doesn’t get enough attention: the hardships stemming from court debt can last decades. Like other states, Virginia has rules specifying the length of time that a lawsuit may be filed in court, including lawsuits that seek to collect outstanding debts. These rules are commonly referred to as statutes of limitations. A closer look at the statutes of limitations reveals why court debt specifically casts such a long shadow. For most kinds of debt, the default rule in Virginia is that creditors have 10 years to enforce a court judgment and collect the debt, although the law does permit extensions under certain circumstances. But when it comes to court debt, the rules are much different and more harsh. The statute of limitations is 30 years for fines and fees imposed by a general district court and 60 years when the debt is imposed by a circuit court. Under such a scheme — one that locks many people into cycles of debt they cannot escape — the only winners are the debt collectors. For many people in Virginia, especially those least able to pay, it’s possible for court debt to follow them for the rest of their lives.

But such counterproductive laws are not inevitable. Several states across the country have already enacted model reforms that Virginia can learn from. For instance, in 2021, Illinois shortened the statute of limitations period for debts related to violations of laws and regulations at the local level. In 2022, Washington state passed legislation to strengthen protections for people with limited or no ability to pay court debt by limiting court debt collection enforcement to ten years, and by allowing individuals to petition forgiveness for their court fines at any time. Furthermore, in places like Wisconsin and Mississippi, the right to collect outstanding debt is explicitly prohibited in the law once the statute of limitations expires.

Moving forward, lawmakers should support comprehensive reforms to Virginia’s system of fines and fees — including changes to the statutes of limitations — that would help more people in Virginia escape poverty and have greater economic opportunity. Bills introduced in the House (HB 857) and Senate (SB 514) would help to accomplish this goal by reducing the statute of limitations for court debt collection to 10 years for both circuit and district court.

The bills would reform existing law by:

- Establishing a uniform 10-year statute of limitations, rather than a 30 or 60 year standard depending on the court;

- Starting the statute of limitations period from the date of judgment, rather than the date of offense;

This practical and meaningful change would ensure Virginians are not trapped in a lifelong cycle of poverty. Community leaders and advocates have been working tirelessly to make sure that our legal system advances justice, treats people fairly, and allows people to grow beyond their mistakes. Lawmakers should follow suit and support these critical efforts.

Category:

Decriminalizing Poverty