April 4, 2016

The High Price of Virginia’s Low Felony Theft Threshold

Virginia’s felony theft threshold – the value of stolen money or goods above which misdemeanor theft becomes a felony – hasn’t increased since 1980 when it was set at $200. But prices go up, which means a crime that was a misdemeanor even a few years ago could now be a felony just because of inflation.

Fixing this should be common sense. But Virginia’s lawmakers continue to refuse to update the threshold even though it arbitrarily damages lives, costs the state millions of dollars per year, and doesn’t deter theft.

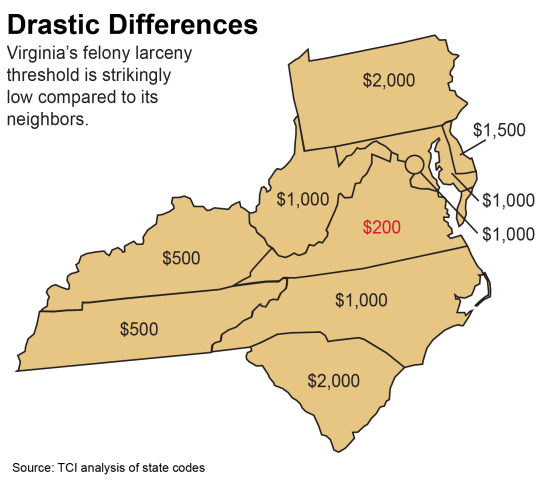

In December, the Virginia Parole Commission recommended raising Virginia’s felony larceny threshold to at least $500 because it would “result in fewer felons, a reduction in the prison population, and system-wide criminal justice cost savings including prosecution, court and prison costs.” Nevertheless, none of the seven pieces of legislation aimed at raising the threshold made it through the legislature this session. After another wasted opportunity, Virginia remains tied with New Jersey for the lowest threshold in the country.

When laws are broken, there should be consequences that carefully balance the costs to individuals, families, and the state with the benefits of deterrence and rehabilitation. And justice should be proportional to the crime.

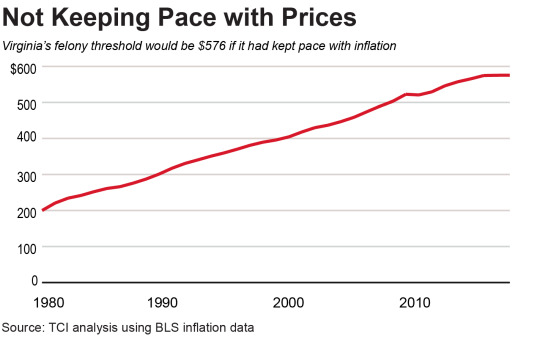

In 1980, lawmakers set the line between misdemeanor and felony larceny at $200. This meant that in general, theft under $200 would result in a maximum punishment of up to 12 months in jail and a $2,500 fine, and theft over $200 would result in one to 20 years in a state correctional facility. Years of inflation mean that this once carefully designed line is now arbitrary, covering far more people and actions than those legislators intended in 1980. If the $200 threshold had kept pace with increasing prices, then it would be about $576 today.

But even if Virginia’s threshold had kept pace with inflation, it would be significantly lower than most of its neighbors. North Carolina, Washington D.C., West Virginia, and Maryland all have thresholds of $1,000. Delaware has a threshold of $1,500. In South Carolina and Pennsylvania it is $2,000.

Raising the threshold also would save Virginia money. According to a Department of Corrections report, the state could have saved between $18.3 million and $22.5 million just in prison costs between fiscal years 2009 and 2014 had the General Assembly raised the threshold to $500 or $600 in 2008. The savings would have been even higher with a $1,000 threshold like North Carolina or a $2,000 threshold like Pennsylvania.

And there are also broader human and economic costs from keeping a very low felony threshold. People can’t fully contribute to the economy from behind bars. And a person’s work skills can diminish during incarceration. But even if a felon maintains or adds skills while in prison, it is tougher to find employment with a felony record than a misdemeanor. And, all too often, long periods of incarceration result in broken marriages and challenges for children.

And, despite fears by opponents, raising the threshold for felony theft does not lead to increases in crime. According to a recent study by The Pew Charitable Trusts that looked at 23 states that raised their felony thresholds between 2001 and 2011:

- Raising the felony theft threshold has no impact on overall property crime or larceny rates.

- States that increased their thresholds reported roughly the same average decrease in crime as the 27 states that did not change their theft laws.

- The amount of a state’s felony theft threshold—whether it is $500, $1,000, $2,000, or more—is not correlated with its property crime and larceny rates.

Crime should be punished. And the appropriate punishment must be carefully decided by elected officials through serious debate. Virginia’s out-of-date felony larceny threshold has massive human costs, unnecessary budgetary costs, and does little to promote law and order. It’s well past time for a change.

Category:

Decriminalizing Poverty