July 29, 2021

As a State of Many Languages, Virginia Needs Language Access

Public resources should be easily accessible to everyone who needs it, regardless of the language they speak. According to 2019 census data, roughly 212,000 people living in Virginia reported that they either do not speak English or speak English ‘not well’. For people with limited English proficiency (LEP), the lack of translated materials and interpretation services keeps important information out of reach. During the pandemic, this can mean missing lifesaving COVID-19 updates. At any time a family is struggling to make ends meet, it could mean getting left out of important programs like rent relief. While some progress was made in the 2021 legislative session to advance greater language access, state lawmakers should take further steps to make sure that consistent and comprehensive language support is available for our diverse commonwealth.

Virginia’s state agencies have so far relied on error-prone automated translations, hard-to-navigate interpretation services, and uncompensated bilingual community members to address the language barrier. This patchwork system has proven insufficient at clearly communicating to LEP families. For example, rather than employing bilingual staff or using vetted translators, the Virginia Department of Health used Google Translate to create their Spanish-version vaccine information page. As a result, the website erroneously stated that “the vaccine is not necessary” instead of “the vaccine is not required,” leaving a confusing message for Spanish speakers.

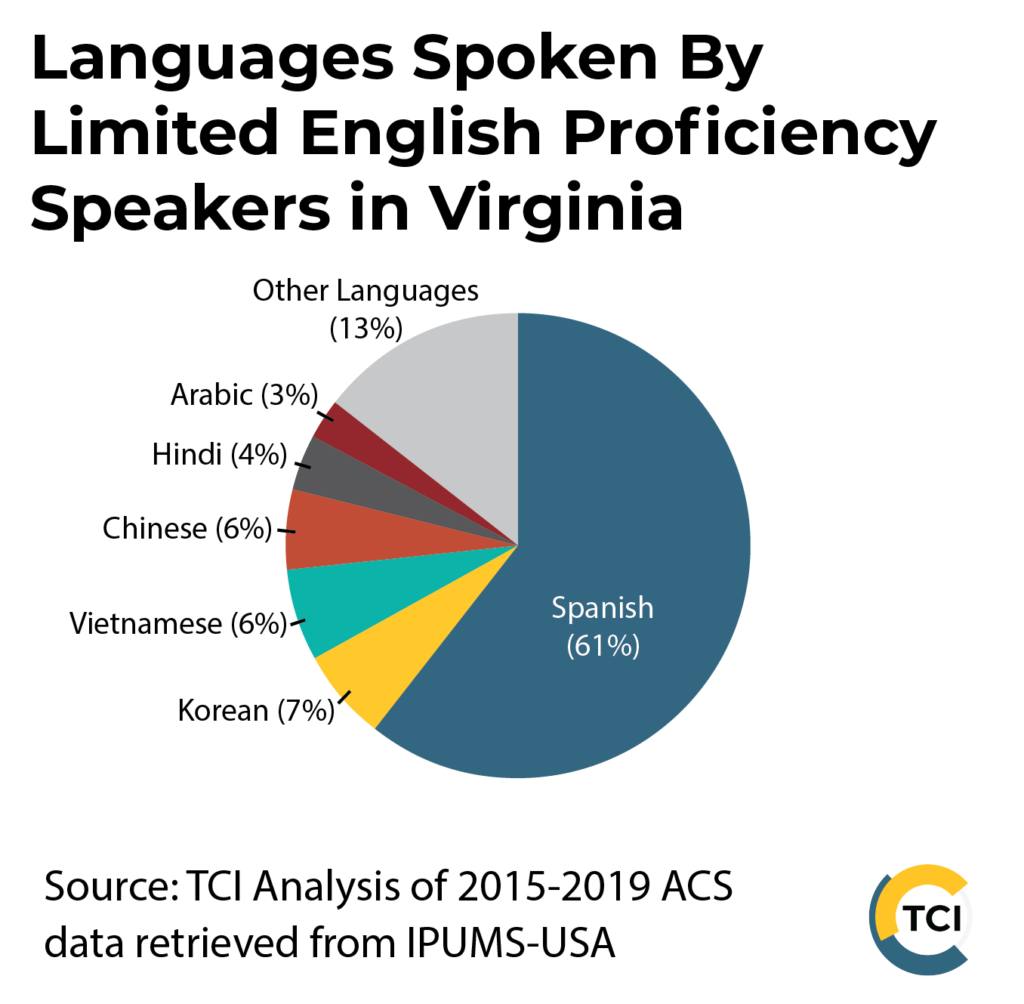

Spanish speakers make up a large portion (61%) of the LEP population, but LEP individuals in Virginia speak a large variety of languages. Around 29% of LEP households in Virginia speak in Asian languages. After Spanish, the most commonly spoken languages by LEPs are Korean, Vietnamese, Chinese (includes Mandarin and Cantonese), Hindi, Arabic, Farsi, and Amharic.

While speakers of many languages call Virginia home, the quality of language access in Virginia varies from agency to agency as there are no statewide language access guidelines. Consequently, many state agencies fail to offer their services in the languages that the people they serve are most comfortable using. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated language barrier challenges as many Virginians, including LEPs, were directed to state agencies to navigate an unprecedented public health and economic crisis. The Virginia Employment Commission (VEC), which manages the state unemployment insurance program, provides an illustrative example. Throughout the pandemic and recovery, the VEC has consistently placed last in the nation in timeliness of processing unemployment claims. Over the last six months, the VEC has only reviewed 2.7% of claims within the federally recommended 3-week processing period. For LEP families, the additional hurdle of a language barrier makes this slow process even more difficult.

“The [unemployment insurance] application itself was only provided in English and Spanish” said Sarah San Sung Choi, a Korean community organizer at the Hamkae Center, “and people had no idea how to apply.” For the Asian American LEP community members that Choi assists, the lack of translated materials seriously complicates the already tedious process of applying for unemployment insurance. “It was ongoing stress,” Choi noted, “we could see the struggle coming from the community members.”

Even when the VEC clarified that interpretation services were available over telephone, it was unclear how to reach them. In a petition to the VEC, the Hamkae Center reported that calls to the unemployment insurance center “automatically cut off if the caller does not choose either the English or Spanish language line,” leaving Asian American LEPs without an option. Without any translated materials or accessible interpretation services, many Asian American LEPs resort to using bilingual family members, many of whom are children, as translators. “The kids do not know how to do these applications, and it has to be completely translated by them,” said Choi. “As an immigrant myself, I help translate for my parents, and I know how hard it is on young kids.”

By failing to remove language barriers, the VEC shifted the responsibility of translation work from their own agency to the LEP families they are meant to serve. These complications made it drastically more difficult to receive benefits, leaving LEP families without financial assistance in a time of crisis. In a state where so many families speak non-English languages, this is unacceptable.

However, some state agencies have proactively addressed language access to better serve Virginia families. The Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS) is one such state agency. This year, DMAS released a report that examines the needs of people who are LEP who access health coverage through Medicaid and details their plan to better accommodate them. In their report, they found that 5 percent of people enrolled in Medicaid (80,846 members) self-identified as speakers of other languages with the top five being Spanish, Arabic, Vietnamese, Urdu, and Amharic.

To serve the LEP population, DMAS is working on a variety of strategies. They aim to internally develop language access trainings, establish quality control standards for language services, gather input from LEP stakeholders, and collect more data to be up-to-date with LEP needs. This comprehensive strategy sets DMAS on the path to remove barriers to access and provide meaningful support for the LEP community.

These examples suggest that the degree to which a state agency is accessible to LEP families is entirely dependent on their internal commitment to language equity. For LEP families, inconsistent language access means being less likely to receive support. Whether or not state services are accessible to LEPs should not be left to chance.

Other states with similar issues have proposed implementing language requirement standards across state agencies to ensure consistent language support. In Massachusetts, legislators introduced a bill during the 2021 session that would require all state agencies to abide by new language requirements recommended by a ‘Language Access Advisory Board.’

In Virginia, legislators have also started to recognize the need for better language access. In the February 2021 special legislative session, Del. Tran and Sen. McClellan championed a budget amendment that committed $100,000 to the Department of Social Services to “increase interpretation and translation services to help immigrants in Virginia access local resources.” Lawmakers also passed budget language (also championed by Del. Tran and Sen. McClellan) that directs the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion to “develop recommendations [in consultation with other agencies and organizations] to implement a language access policy for Virginia state government to ensure equitable access to state services for Virginians who are limited English proficient.”

Once the workgroup releases its recommendations, state lawmakers must act with urgency as LEP families are still being left out of state agency services that they direly need. State lawmakers should establish standardized language access requirements across all of Virginia’s state agencies and ensure the sustainable revenue necessary to invest in continued, meaningful access. Lawmakers could explore using the state’s share of $2 billion in American Rescue Plan Act funds that will be distributed to states to promote equitable access to unemployment benefits, among other uses. By creating more comprehensive and more consistent language support, lawmakers would remove language barriers for LEPs living in Virginia and support new access to crucial public resources. As a home to speakers of many languages, it’s time that Virginia invested in the support to meaningfully serve our families.

Category:

Immigration