July 25, 2018

Virginia’s 10-Year Tide Hasn’t Lifted All Boats

2008 was 10 long years ago, but the effects of the Great Recession are fresh enough that the nation’s worst economic downturn since the Great Depression is still an open wound. In light of new jobs and wages data, just how far has Virginia’s economy bounced back to work? And who is it working for?

The news is not all bad. As of June 2018, unemployment in Virginia has dropped to pre-recession levels – 3.2 percent, the 13th lowest rate in the country. There are also 224,900 more jobs now than there were in December 2007, a 6 percent increase. Wages for some workers have enjoyed modest gains as well – the median Virginian worker earned 4.6 percent more in 2017 than in 2007 after adjusting for inflation.

But even by these metrics, Virginia’s recovery since “the big one” has been slow compared to previous recessions. The 1990 downturn, for example, was particularly tough on Virginia’s workforce due to federal cuts in defense spending. But 10 years afterwards, the commonwealth had 23 percent more jobs than before the recession began. Ten years after the 1981 recession, jobs were up 31 percent. Virginia’s 6 percent increase since December 2007 pales by comparison.

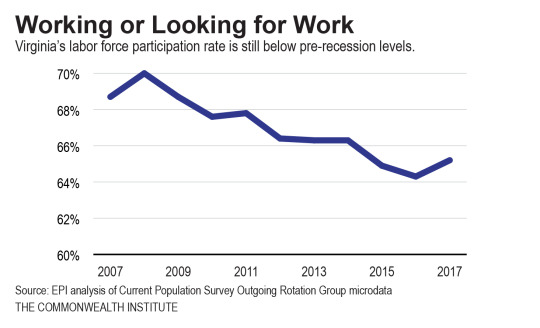

What’s more, recent slow-and-steady job growth isn’t sufficient to make up for the “jobs hole” that was dug during the Great Recession, when Virginia’s working-age population grew even as jobs disappeared. Virginia’s working-age population has leaped 13 percent since December 2007, well ahead of the 6 percent jobs growth. That means there are still 267,071 missing jobs in Virginia compared to the state’s pre-recession employment rate. And while unemployment is down, part of that is due to a sliding labor force participation rate – a smaller share of working age adults are working or looking for work. While Virginia saw a slight increase in 2017, the labor force participation rate is still below 2007 levels.

Caveats aside, a rebounding jobs and wages outlook could inspire complacency about the economy as it continues to recover from the 2007-2009 recession. After all, Virginia’s median wage remains one of the highest in the country. But a report card on the economy can’t be reduced to overall jobs and wages trends. And unfortunately, the gradually rising tide of Virginia’s economy has not lifted all boats.

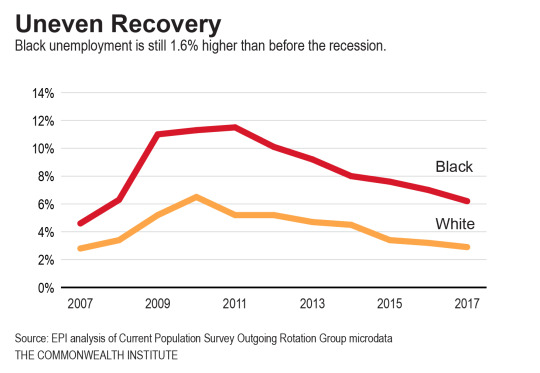

The inequities of Virginia’s recovery are particularly pronounced along racial lines. In 2017, for example, White unemployment in the commonwealth shrank to near-2007 levels, whereas Black unemployment – having peaked at over 11 percent in 2011 – was still 1.6 percentage points higher than before the recession.

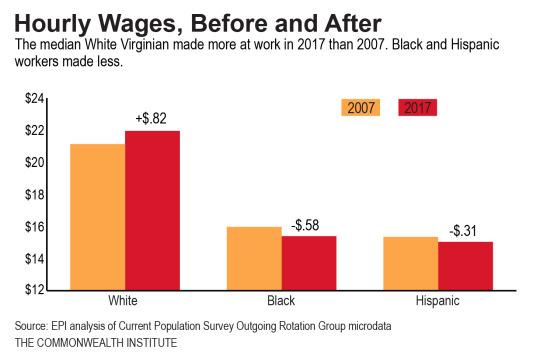

Virginia’s paychecks tell a similar story. While wages for Black and Hispanic workers in the United States (let alone Virginia) have never matched White wages, in recent years it’s gotten worse. The median White worker made $0.82 more per hour in 2017 than in 2007 after adjusting for inflation, while Black and Hispanic workers made $0.58 and $0.31 less, respectively. And this is not just the state by-product of a national trend – Black and Hispanic median wages in the country as a whole marginally increased over the same time period.

In light of this troubling trend, Virginia should take a hard look at how it plans for economic recoveries with a special focus on how policies impact the schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces that educate, house, and employ Virginians of color. Addressing any of the persistent barriers to economic prosperity that communities of color regularly and disproportionately face could help.

For instance, an end to the practice of suspending driver’s licenses due to unrelated court fines and fees as well as broader access to driver’s licenses for immigrants would help many Black and Latinx Virginians access jobs that currently go unfilled. Potential savings from ending mass incarceration could be reinvested into creating job opportunities for those who have been caught up in the system.

Policymakers have other tools at hand to boost economic opportunities for low-income families of color who have faced barriers to full participation. A refundable state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) would allow families to keep the full amount of the credit, helping low-income working families offset the other state and local taxes they pay. Increasing the quality and availability of early childhood education would give working families more flexibility in their career paths and reduce barriers to success for children from low-income families. Finally, a higher minimum wage would have a particularly beneficial impact for Virginians of color.

There is no single piece of legislation that will close this gap overnight – rather, state and local policy leaders should look to multifaceted strategies to ensure an equitable rebound from economic distress. In a growing and diversifying state, it is more important than ever to advance policy solutions that lift all people in Virginia.

Category:

Economic Opportunity