December 18, 2023

Fair Share Taxes: A Simple, Effective Solution to Invest in Our Communities

Whether we have $10 to our name or $10 million, we all want to live in a state with good public schools, safe transportation, clean air and drinking water, affordable housing, and high-quality health care systems. To accomplish these shared goals, Virginia needs sustainable revenue to correct years of underfunding and invest in these building blocks of thriving communities for years to come. Unfortunately, a greedy few and special interests have rigged the tax code to get out of paying their fair share. Now, Virginia’s tax code is upside-down — the wealthiest pay the least taxes as a share of income — and it limits our ability to invest in our communities.

In response to budget “surpluses” in recent years, elected officials proposed harmful tax cuts that would have doubled down on the challenges with Virginia’s tax code — further benefiting the wealthy and large corporations and draining future resources — instead of prioritizing the many unmet needs in our communities. For instance, the state provides 21% less funding to schools than the national average, and billions are needed to fully fund our schools. Over 86,500 children in Virginia are without health insurance, which has life-long implications and requires substantial state funding to remove barriers and connect children to coverage. And across the state, tens of thousands of families face an eviction crisis, coupled with an underlying housing affordability crisis, that requires a robust investment. To address these and other needs, we must focus not on tax cuts, but on protecting and raising adequate resources.

Lawmakers have the opportunity, and should boldly act, to advance tax fairness so that we can invest in all of us. A simple and effective solution to making sure that everyone pitches in their fair share: a millionaire’s tax in Virginia. Establishing this “fair share tax” would raise approximately $1 billion each budget year that can be used to meet the needs Virginia residents have continually identified in their communities and to fund the programs and services that will benefit all of us.

Virginia’s Outdated Income Tax Structure Holds Us Back

Where we are

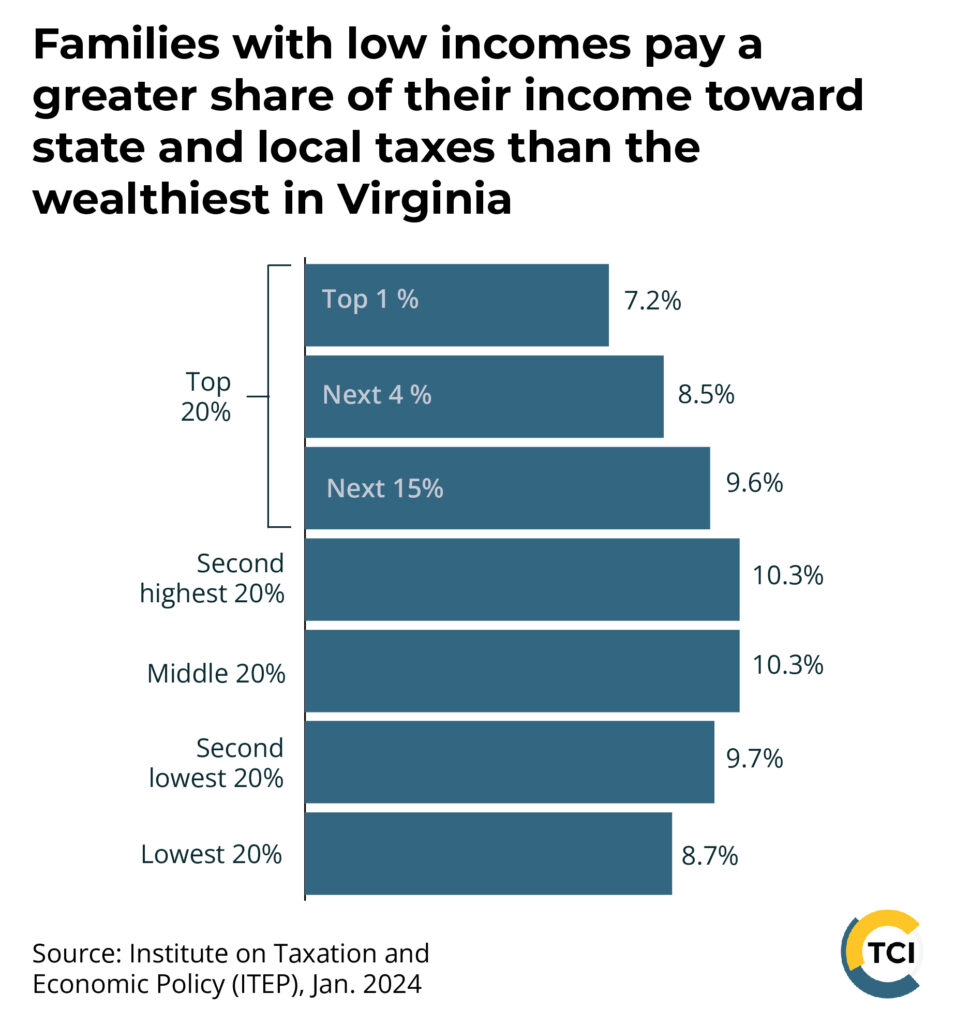

Virginia has an upside-down tax code: when considering all forms of state and local taxes — income, sales, and property taxes — families with lower incomes in Virginia pay a greater share of their income on taxes, while those with the highest incomes pay less. In recent years, lawmakers made some progress in addressing the upside-down structure, adding an option to the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) that allows families to receive more of the credit they earned, increasing the standard deduction, and removing the state sales tax for grocery and hygiene items. However, more work needs to be done to create a truly fair tax structure that makes sure the wealthiest among us are paying their fair share and provides the resources needed to invest in communities.

The current income tax in Virginia is an artifact of its incremental, then stagnant development. Virginia has had a version of an income tax on the books since 1843, and was an early adopter of the modern state income tax in 1916 — one of the first six U.S. states to do so. In the more than one hundred years since its adoption, the state income tax has become a key revenue source for the general fund, the part of the budget for which lawmakers have the most flexibility and is primarily used for programs like education and health and human services. State income tax collections comprise nearly three-quarters of general fund revenue collections, as of the budget year that ended June 30, 2022 (fiscal year 2022).

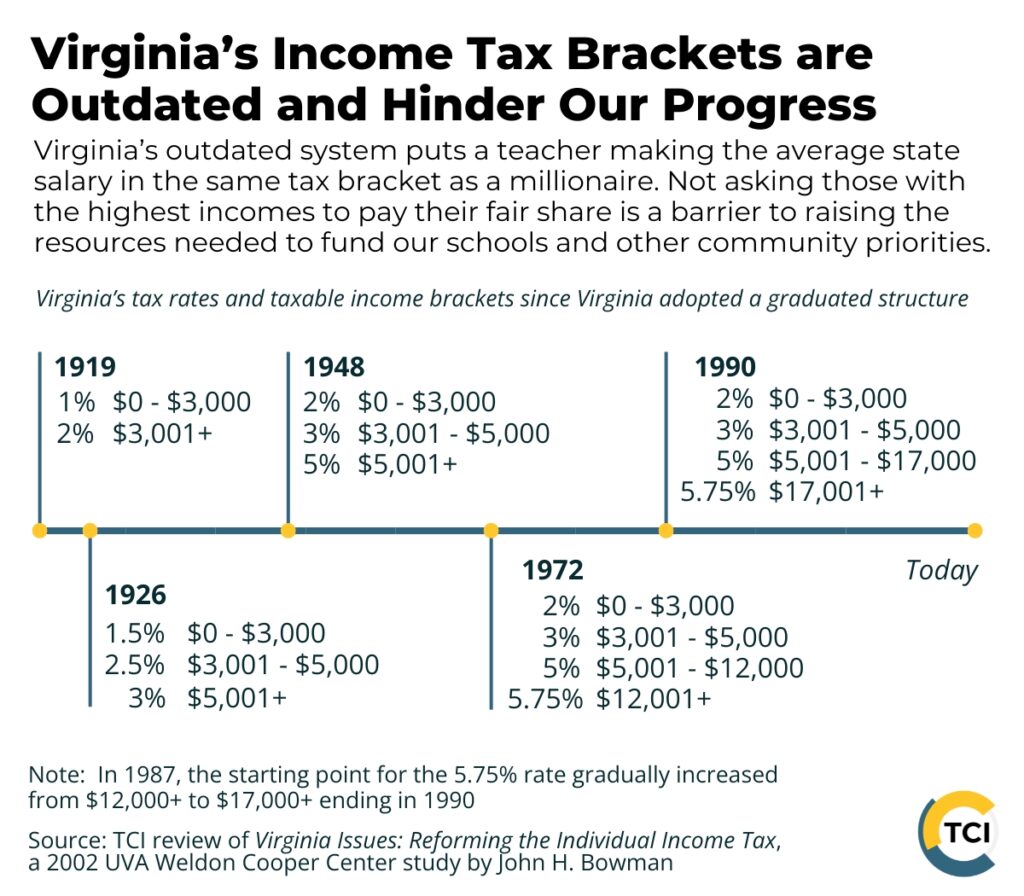

While Virginia’s current income tax brackets have been in place since 1990, there has been surprisingly little change in its century-long development.1 Virginia adopted a graduated rate structure in 1919, with people paying 1% in taxes on the first $3,000 of taxable income (income after exemptions and deductions) and 2% on taxable income over $3,000. The threshold for the first income tax bracket ($3,000) remains unchanged. In 1926, with a new bracket added, people paid 1.5% on the first $3,000 of taxable income, 2.5% on the next $2,000, and 3% on income over $5,000. In 1948, the marginal rates were updated to 2%, 3%, and 5% respectively. These first three rates remain unchanged to this day. Further reform did not happen for another 24 years. In 1972, lawmakers added a fourth (and currently final) bracket, and people began paying 5.75% on taxable income over $12,000. The starting point for the fourth bracket was gradually increased to $17,000 between 1987 and 1990. The state’s income tax structure has remained untouched in the three decades since then.

While progressive in structure — people pay a higher tax rate as their ability to pay increases — the top bracket has a relatively low threshold of taxable income. People pay 5.75% on all taxable income over $17,000 in Virginia, and decades of inflation have pushed greater portions of Virginians’ incomes into the top state income tax bracket. This outdated system puts a teacher making the average state salary of $61,367 in the same top tax bracket as a millionaire and is a barrier to raising the resources needed to fund our schools and other community priorities.

Momentum for change

Lawmakers have recently considered adjusting the state income tax brackets. However, the proposals failed to advance fairness in the tax code, failed to raise essential revenues, or both. During budget negotiations in 2023, negotiators considered (though, ultimately, did not pass) several proposals to alter the personal income tax structure, including decreasing the top income tax rate and adjusting the bracket thresholds. Decreasing the top income tax rate would have given greater benefits to the wealthiest in the state, while doing very little for middle- and lower-income families. While proposals to alter the income tax varied in size and impact, none managed to raise revenues or ensure the wealthiest among us pay their fair share.

Calls to adjust the three-decades-old state income tax structure are nothing new. A 2002 study by John H. Bowman (at the time an economics professor at Virginia Commonwealth University) for the University of Virginia Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service suggested that lawmakers reimagine the state income structure. Almost two decades later, the state legislature asked their independent research agency (Joint Legislative Audit & Review Commission, JLARC) to research the matter. JLARC created a report outlining a menu of 10 options to make the state income tax more fair.

A Fair Share Tax is A Simple, Effective Solution

In their 2022 report on how to make the state tax code more fair, JLARC outlined 10 options, four of which would raise much-needed state revenues. Two recommendations are estimated to raise $1 billion in new state revenues, including adding a new tax bracket that would have a very small share of people pay 10% on taxable income over $1 million.

How would creating a fair share tax work?

A fair-share tax would help clean up our tax code by adding a new and long overdue bracket to Virginia’s income tax structure for the first time since 1972, making sure those in the state with high incomes contribute their fair share. The vast majority of people in Virginia would see no change in the income tax they pay, and they would still pay 5.75% on taxable income from $17,001 to $1 million. A small group would pay a 10% tax rate — just 4.25 percentage points more than before — on any taxable income over $1 million. If someone made $1,000,001 in annual taxable income, they would only pay 10% on that last dollar.

Very few people would pay a fair-share millionaire’s tax

JLARC’s research shows that very few Virginians would pay higher taxes under this proposal. An estimated 17,700 Virginia tax filers — about 0.4% of the over 4 million tax filers in the state — would be impacted, meaning that 99.6% of filers would not see a tax increase. Of those who would, their Virginia individual income tax would increase by just 2% on average.

“JLARC’s research shows that very few Virginians would pay higher taxes under this proposal — an estimated 17,700 — and that 99.6% of filers would not see a tax increase.”

Only “income millionaires” — anyone who reports over $1 million of Virginia taxable income within a span of one year on their income tax returns — would pay the higher tax. This narrows the scope of the tax, as it does not consider everything that plays into net worth, like held assets, in its definition. What is considered taxable individual income varies between the state and the federal government.

In Virginia, the value of assets would only be considered if a profit is made (also known as “realized capital gains”), and only the profit, when applicable, would be considered income. For example, owning a boat does not increase your income, but if you have a boat that you fix up and then sell for a profit, the profit (the price of the boat when it sells, minus the cost when it was bought and the cost of improvements) could be considered taxable as a capital gain. While sometimes taxed differently at the federal level, Virginia mostly considers capital gains and certain qualified dividend income as taxable individual income.

There are additional circumstances where a share of profits may not be included in taxable income calculations. For instance, long-term capital gains from investment in some types of ‘qualified businesses’ get special treatment in Virginia under certain conditions: including advanced computing, agricultural technologies, and nanotechnology just to name a few. And Virginia conforms to some federal tax rules around the sale of primary residences, particularly a $250,000/$500,000 capital gains exclusions.2 If a married couple sold a house under qualifying conditions and made a $500,000 profit, that profit would be canceled out by the capital gains exclusion and would therefore not be subject to the state income tax.

Some other asset sales are also included in the state’s income tax calculation. While holding income in a typical retirement account does not increase someone’s income, a withdrawal from the account could do so. For example, lump sum disbursements from typical retirement accounts that may provide boosts to annual income would be subject to the state’s income tax, though age deductions may reduce the amount of taxable income for retirees. Withdrawals from Roth retirement accounts are not counted as part of income, and do not typically face taxes except in some cases of early withdrawals.

When are assets taxable? Examples of how capital gains are taxed in Virginia and how they could be impacted by a fair-share millionaire’s tax.

Home Sales. When someone sells their primary residence, the first $250,000 of increase in home value, or $500,000 for married couples, is exempt from taxation. A state fair-share tax for millionaires would only impact an individual selling their home if their home value increased more than $250,000 AND their income in addition to the home sale totaled over $1 million. If someone’s income was just from the sale of their home that year, they would have to sell their home for over $1.25 million more than they bought it to face any higher tax rate.

Retirement Savings. Withdrawals from traditional retirement accounts are taxed as ordinary income at the federal and state level. If a person withdrew more than $1 million in a single year, or if the withdrawal plus other income was more than $1 million in a year, they could face higher taxes on income that surpasses $1 million.

Withdrawals from Roth retirement accounts are not counted as part of income and are not taxed except for some early withdrawals of earnings.

Selling Stocks. Income from long-term capital gains face lower taxes at the federal level, but are taxed at the individual income rate at the state level. If someone sells stock they have for $1 million above purchase price, or if the the profit from the sale plus their other income is above $1 million, their income over $1 million could be taxed at a higher rate under a fair-share millionaire’s tax.

State tax policy rarely influences where someone lives

We all want to live in a state where we, and our neighbors, can thrive. Yet a greedy few and special interests are doing everything they can to get out of paying their fair share, including spreading fear and misinformation about how millionaires will respond to paying a higher tax. The truth is that while income millionaires are more likely to consider state tax rates while making a move, they are far less likely to move than the general population. Income millionaires tend to be more embedded in place than the rest of the population due to a variety of factors. Income millionaires are more likely to be married, have school-aged children, own businesses, and are often at the peak of their careers in jobs that are difficult to relocate.

Even with recent events, like the introduction of the federal state and local tax (SALT) cap, which limited the deductibility of state and local taxes, and the rise of flexible remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic — factors that would theoretically incentivize people with high incomes to leave high tax states for low tax states — there has yet to be a mass exodus from higher tax states to supposed lower tax havens. While some have trickled out, not enough high-income households are leaving higher tax states to offset the revenue gains. Researchers have found that states would have to tax millionaires at much higher marginal rates to even maximize revenue gain over out-migration, far higher than any state taxes high incomes. The research consensus is clear: “Millionaires are not searching for economic opportunity — they have found it.”3

When it comes down to it, taxes are rarely the primary cause for any family to leave a state. People leave their states for employment opportunities, to be closer to family, to find more affordable housing, and for better lifestyle fits. Raising revenues and investing in strong public education, safe and affordable housing, accessible health care, and safe transportation makes a state a more desirable place to live. Lawmakers’ tax choices should focus on helping families to thrive, not protecting the wealthiest among us from paying their fair share.

A Fair Share Tax Would Bring More Resources, Greater Equity

A new tax bracket on income over $1 million would help us create sustainable revenue streams to fund our shared priorities and would help to address some inequities that keep communities from thriving. JLARC’s report on options to make the state income tax more fair found that a higher tax rate for millionaires could bring in over $1 billion in state revenues annually, which lawmakers could use to make significant investments in long-underfunded public services like public education and affordable housing.

New revenues in the face of economic uncertainty

Virginia, like many other states, has seen several years of budget “surpluses,” with revenues boosted by COVID relief dollars from the federal government and better-than-expected collections during unpredictable times. While lawmakers used much of these surpluses on one-time spending (such as limited tax rebates and flexible funds to schools), a substantial portion went to permanent tax cuts, resulting in a permanent dent in future revenues. However, the future of the state’s revenues is more uncertain. In recent presentations to the state legislature’s money committees, budget forecasters shared that they anticipate an economic “soft landing” or “mild recession.” This has resulted in more conservative assumptions about revenue growth in the budget, leaving very little flexibility to expand on budget priorities. As of November 2023, legislators expected just $878 million in available resources above the base budget and mandatory spending for the 2024-2026 budget cycle, a far cry from the billions they saw in recent years. A powerful and new revenue source could breathe life into the budget, adding critical resources to help fully fund our communities’ priorities.

A safeguard against austerity

As we face new economic uncertainty, lawmakers must establish new revenue streams so that public services are not only maintained but improved. Cutting public investment in the foundations of our communities in the name of so-called “fiscal responsibility,” otherwise known as austerity measures, harms our communities in the long run. Continuing to threaten tax giveaways to the wealthy and profitable corporations is contrary to fiscal responsibility and will erode investment in our collective priorities. In the past, the lack of safeguards for communities around austerity measures resulted in lawmakers cutting critical public resources, with significant impacts on low-income communities and communities of color. For example, during the Great Recession, rather than raising new revenues, Virginia lawmakers made cuts to school funding and put limits on future spending. These cuts hit school divisions with the highest poverty rates almost three times harder than divisions with the lowest poverty. Some of these programs still suffer the consequences, with particular harm done to children of color in low-income families. Support staffing decreases at the time were four times larger in school divisions with the highest proportions of students of color than in school divisions with the highest proportions of white students. Establishing new revenue streams now can help protect critical services in the future, especially as the governor encourages cuts across state agencies.

A step toward racial and economic justice

At the end of the day, a new tax bracket would make sure the wealthy few simply pay their fair share. Even with recent actions to make the state tax code more fair, high-income households in the state are still paying a lower share of their income on taxes than low- and middle-income households.

In addition to high-income filers paying less than their fair share, income is becoming more and more concentrated in the hands of the wealthy few in Virginia. Households in the bottom 90% of incomes in Virginia have just 55% of all state income, as of 2018, down from 65% in 1990. The top 1% of incomes in the state account for 16% of all individual income in 2018, up from 11% in 1990. While not as concentrated as the top 1% of incomes nationally, this concentration is part of a global shift of income into the hands of the already well off.

A new tax bracket would also be a meaningful step forward for racial equity in Virginia. As a result of numerous historic and recent policy choices rooted in anti-Blackness — such as systemic discrimination in housing access, lending practices, and education spending, amongst many other factors — it is well documented that Black Americans have faced significant barriers to amassing wealth and income at levels similar to their white peers, and this inequality has persisted across time. In Virginia, median household income for Black households is just 70% of the state median, while median income for white households is 107%. A national-level estimate shows white families are three times more likely to be in the nation’s top 1% of incomes than Black and Latino families.

Our current upside-down tax system exacerbates this inequality, harming Black and Latino communities while allowing wealthier, primarily white, individuals to avoid paying their fair share. Adding a new top tax rate would make sure that the wealthy who have profited from this system pay their fair share so that, together, we can achieve our shared goals. The revenues collected from a new tax bracket would be invested in critical services like education and affordable housing, where underinvestment and systematic discrimination has caused disproportionate harm to Black families in the commonwealth.

Success Stories in Other States

Asking people to pay a higher tax on higher incomes is not unusual. It has been an increasingly popular strategy for states to create sustainable revenue streams while generating greater equity through their tax code. Here are some success stories from a few states that have added higher rates for millionaires.

MA: Through a successful ballot measure in 2022, Massachusetts’s Fair Share Amendment (FSA) approved a 4% surtax on taxable incomes over $1 million. Not only did this help address the state’s upside-down tax code, it also helped fund essential priorities by investing $1 billion of the collected revenues in public transit, education, roads and bridges, and child care. Thanks to the Fair Share tax in Massachusetts, K-12 lunches are now free for all public school students.

NJ: New Jersey has had a long-standing higher rate on high incomes (in 2004, the state established an 8.97% bracket for income over $500,000) and has recently established new brackets for millionaires. In 2018, the state established a 10.75% bracket for taxable incomes over $5,000,000. In 2020, the top rate was extended to apply to taxable income above $1 million. The new tax was estimated to bring in $400 million a year.

NY: New York has had higher tax rates on high incomes since 2011, and now has multiple tax rates on income over $1 million, ranging from 9.65% on taxable income between $1,077,551 and $5 million to 10.90% on taxable income over $25 million for single filers. This has raised critical revenues for public services. While reporting notes that some millionaires left New York in 2020 and 2021, this is hardly enough to offset the increasing number of millionaires in the state. In 2020 and 2021, 3,400 millionaires left the state. However, the overall number of millionaires in New York still increased by 10,000 during the same time frame.

CA: California’s top income tax rate is 12.3% on taxable income over $698,272 for single filers and $1,369,543 for married filers. There is an additional 1% surcharge on taxable personal income over $1 million. The surcharge was established in 2004 to make transformational investment in the state’s behavioral and mental health system.

D.C.: While not technically a state, D.C.’s tax code is one of the most fair in the country when ranked among all U.S. states. From 2016 to 2021, D.C. residents paid an 8.95% tax on taxable income over $1 million. Beginning in 2022, residents began paying 10.75% on taxable income over $1 million. This was coupled with other rate increases for high-income households, which raised a combined $100 million in new revenues for the district and supplemented a budget that invested in affordable housing and eviction prevention.

Raising $1 Billion for All of Us

A fair-share tax for millionaires could raise $1 billion in sustainable state revenues and fund vital public services that everyone in Virginia relies on while making our tax code more fair. Raising revenue gets us closer to a Virginia where all can thrive: where every student in every zip code has access to a high-quality public education, where everyone has access to safe and affordable housing, and where the wealthy pitch in their fair share to the communities where they have found economic opportunity. In imagining our collective futures, we must advance policies that provide meaningful services to our neighbors, and lawmakers must fund these policies in an equitable and sustainable way.

Endnotes

- Bowman, J. “Virginia Issues: Reforming the Individual Income Tax,” for UVA Weldon Cooper Center, 2002

- This exclusion is said explicitly to apply in VA in this tax department ruling https://www.tax.virginia.gov/laws-rules-decisions/rulings-tax-commissioner/11-48 “In the case of a personal residence, however, IRC § 121 provides an exclusion for a gain from the sale or exchange of a principal residence. Because Virginia begins it computation of Virginia taxable income with FAGI pursuant to Va. Code § 58.1-322, Virginia’s conformity to federal law, as is set forth in Va. Code § 58.1-301 permits an exclusion on the gain from the sale of a principal residence to the extent allowed for federal income tax purposes. As such, if the Taxpayers gain from the sale of their Virginia home does not exceed the amount of the exclusion, no gain would recognized for Virginia income tax purpose.”

- Much of this section derives from the research of Cristobal Young, a leading researcher on millionaire tax migration. Quote is found in Cristobal Young, et al., “Millionaire Migration and Taxation of the Elite: Evidence from Administrative Data,” 2016