September 28, 2018

Medicaid Premiums and Copayments Will Make it Harder for Low-Income Virginians to Access Needed Care

The Virginia General Assembly passed a budget that directs the state to expand Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in June 2018. Since then, much attention has been given to a provision requiring the state to apply for a waiver from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to impose a work requirement on certain low-income Medicaid enrollees in Virginia.

The Virginia budget also instructs the state to include in its waiver request a provision requiring certain Medicaid enrollees with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the federal poverty line to pay premiums and copayments in order to access their coverage. That means new costs would be applied to families with incomes between around $12,000 for an individual on the poverty line, up to $35,000 for a family of four at 138 percent of the poverty line. If these enrollees fail to make these payments, they can be locked out of their health coverage until they are able to afford payments again and will face debt collection.

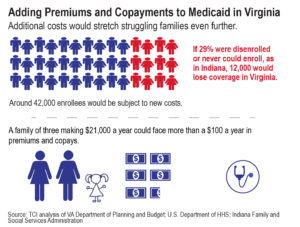

Most current adult Medicaid enrollees in Virginia are already subject to some copayments for services in the range of $1 to $3 per visit. Under this waiver, an estimated 42,000 low-income Virginia Medicaid enrollees would be subject to premiums and an additional copayment.

Virginia is pursuing this policy even though research shows that Medicaid premiums and copayments make it harder for low-income people to receive the care they need and in many cases fail to lower costs. A handful of states have imposed similar financial requirements on low-income Medicaid enrollees to what Virginia proposes. In response to these new patient costs, use of medical services has declined or been delayed, long-term medical costs have risen as preventative medical visits have fallen, substantial numbers of people have been removed from the program or locked out of coverage, debt and financial hardship has increased, and unhealthy behaviors have increased. And non-emergency use of hospital emergency rooms (ER) has failed to decline in any significant way. Further, these policies are not cost effective. Multiple states, including Virginia, have found it costs substantially more to collect these types of payments than can be raised in revenues from them. Similarly, studies of Medicaid copayments have for the most part failed to show a decline in the number of costly emergency room (ER) uses for non-urgent care. These findings show Virginia lawmakers and state officials should proceed with extreme caution as they seek to impose these new requirements on Medicaid enrollees.

Major Legal Barriers and Costs to be Expected

Virginia must apply for permission from the federal government to implement premiums and higher copayments for Medicaid recipients through what’s called an 1115 demonstration waiver. Other states, such as Michigan, Indiana, and Kentucky, were recently approved to implement similar requirements. However, a federal district court blocked Kentucky from moving forward with implementation of its 1115 waiver to implement work requirements and premiums on a portion of its Medicaid population. The court ruled that those who would have to pay the new premiums “would suffer a concrete injury from Kentucky HEALTH.” The court found that creating additional financial barriers to health coverage for low-income families undermines the intent of 1115 waivers, which are meant to improve health and wellness. If allowed to proceed, Virginia’s waiver could lead to a similarly expensive lawsuit in federal court.

The Impact of Premiums and Copayments: What the Research Shows

The Virginia budget states that premiums and copayments are “designed to promote healthy behaviors such as the avoidance of tobacco use, and to encourage personal responsibility and accountability related to the utilization of health care services such as the appropriate use of emergency room services.” The budget also recommends the creation of health and wellness accounts for low-income individuals subject to premiums and higher copayments. The accounts would be used to help pay for the individuals’ medical expenses over time. Enrollees who comply with intended behaviors (such as getting vaccines or certain screening visits) will receive a 50 percent reduction in their monthly premiums. Yet the outcomes of similar policies in other state plans have proven ineffective and even harmful.

Low-Income Virginians Will Lose Coverage

Virginia has not provided estimates of the number of low-income Virginia families who will be deterred from signing up from coverage because they can’t afford the premiums, or who will lose coverage because they miss their payments. However, the experiences of other states suggest that it will be in the thousands.

In the first two years that Indiana implemented premiums on Medicaid enrollees, more than 57,000 people either never received or missed out on continuous Medicaid coverage because of the new requirements, representing 29 percent of the total people who were subjected to the new requirements (enrollees above 100% federal poverty line). If 29 percent of the Virginia Medicaid enrollees subject to premiums and copayments were removed from coverage for failure to meet the new requirements, that would translate to more than 12,000 low-income Virginians denied coverage. In Indiana, more than 13,000 were disenrolled from coverage they were in the middle of receiving, and more than 46,000 could not be initially enrolled because they failed to make their first premium payment. A majority of those who missed their premium and cost-sharing obligations in Indiana’s program indicated that they either could not afford the payments or were confused about how to make them. In Virginia’s proposed waiver, people who failed to pay the premium for three months would lose coverage until they were able to make payments again.

In Michigan, which has a similar premium and copayment program to the one Virginia is seeking, about 56 percent of people between 100 to 133 percent of the federal poverty line were not up to date on paying their premiums and/or copayments as of January 2017. If Virginia sees a similar share of people who do not stay up-to-date with premiums, around 23,500 low-income Medicaid recipients could lose their coverage due to missing payments. While the actual number of people who lose coverage will vary based on the exemptions, outreach, and program navigation assistance offered in the final plan, Virginia can expect thousands of low-income families to lose their health care coverage as a result of premium and copayment requirements. It is, therefore, important for Virginia to further estimate the impact these new requirements will have on the health and well-being of Virginia residents and on the state’s budget.

Medicaid Recipients Could Face Poorer Health

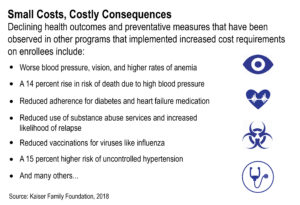

Health outcomes are also expected to worsen for the people who have managed to keep Medicaid despite the new cost barriers. These individuals are much more likely to reduce usage of necessary services such as vaccinations, prescription drugs, mental health visits, preventive and primary care, inpatient and outpatient care, and adherence to needed medications. All essential services for preventing future health complications.

Declining health outcomes and preventative measures that have been observed in other programs that implemented increased cost requirements on enrollees include:

- Worse blood pressure, vision, and higher rates of anemia;

- A 14 percent rise in risk of death due to high blood pressure;

- Reduced adherence for diabetes and heart failure medication;

- Reduced use of substance abuse services and increased likelihood of relapse;

- Reduced vaccinations for viruses like influenza;

- A 15 percent higher risk of uncontrolled hypertension.

A more complete summary of other health outcomes is available through the Kaiser Health Foundation.

These impacts likely understate the problem since some studies only track individuals with coverage and do not include people who lose coverage. When Oregon implemented high copayments and premiums for its Medicaid program, nearly half of the adults subjected to the new requirements lost coverage. Research indicated that these low-income individuals likely experienced significantly worse health outcomes as a result of losing their health coverage than those that could afford to remain in the program.

Confusion Over New Requirements Will Likely Lead to Loss of Coverage

As in most other states that have implemented similar premium and copayment barriers in their Medicaid programs, Virginia enrollees may not be aware of what requirements they must meet to preserve their coverage. This confusion will likely lead to substantial numbers of people losing coverage. Enrollees must learn whether they are required to pay monthly premiums, and if so, must actively make these monthly payments, since there is not yet any indication there will be a system for deductions from paychecks as with most employer-based private insurance.

It will be hard enough for Virginia to set up systems to track premiums and copayments based on each person’s individual income and never to let these costs exceed 5 percent of their total income (in accordance with federal law), but helping low-income families understand the new requirements and keep up with all the paperwork they must regularly submit in order to effectively track this information will be quite challenging. Increased paperwork in other social safety-net programs typically leads to many eligible individuals losing coverage even when they have met requirements or should be exempt. Almost all systems for implementing Medicaid copayments and premiums in other states have struggled to process payments and communicate with certain Medicaid enrollees.

Virginia has not yet publicly specified how it will notify people subject to copayments and premiums. In Kentucky, those who were supposed to be subject to these requirements were primarily sent written notices. This left Kentucky families to interpret the new requirements for themselves, with no guarantee that everyone received the notices. Individuals who may be experiencing homelessness, displacement, or housing instability were even less likely to receive this vital information.

There are also groups of Virginians who will likely struggle to accurately understand or comply with these new requirements. Eligible people with physical disabilities, mental health needs, and substance use disorders have been shown to be much more likely to lose benefits from Medicaid, even if they should qualify for exemptions.

For those who would like to pay their premiums on time, payment methods can present an additional barrier. While most people with private insurance have premiums deducted automatically from their paycheck or bank account each month, Medicaid enrollees in many cases have to manually pay their premiums by mail or by hand. The waiver does say payments will be possible “through a variety of payment mechanisms,” but goes on to only specify pre-payment options and money orders as examples.

Kentucky set up a system that only allowed individuals to pay premiums via credit card or a similar electronic payment method. However, many low-income families do not have access to this form of payment (less than 36 percent of households with incomes below $25,000 had credit cards in 2013). Whether it is by mail or through an electronic transfer, limited payment options make it difficult for some people to comply with requirements, increasing the risk of coverage loss.

Healthy Behavior Incentives are Unlikely to Have the Intended Effects

The Virginia waiver proposes a reduction in premiums and copayments for enrollees who adopt healthy behaviors. These incentive programs typically require a wellness exam and/or completion of a health-risk assessment. Virginia has not yet indicated how exactly it will measure compliance with “healthy behavior” provisions to receive a discount, but has provided some examples of activities that may qualify.

Similar behavioral interventions attempted in other states are not promising. There is currently no strong evidence that states have effectively implemented wellness programs to actually change Medicaid enrollees’ health behaviors.

In Iowa, Medicaid enrollees who completed a health risk assessment could have their premium fees waived. After the first year, less than 10 percent of enrollees with incomes above the poverty line completed the assessment. Around 90 percent of Medicaid enrollees in the state didn’t even know about the program.

Michigan conducted more intensive outreach to enrollees about the cost reductions they would qualify for if they completed a health risk assessment and adopted certain health behaviors. After nearly two years of outreach, only 18 percent of the enrollees had taken advantage of the initiative.

Virginia has not allocated any money specifically to outreach efforts to alert enrollees of this benefit and is unlikely to have many people take advantage of it. Like in other states, this provision will more likely be a confusing element of Virginia’s program that will not significantly ease the financial burden for the people it is aimed to help.

Adding a Financial Burden to Already Struggling Families

Research has demonstrated that when premiums are imposed on Medicaid enrollees, they are typically a significant added expense, leading to substantial drops in enrollment and the creation of debt. In Virginia, individuals will be locked out of Medicaid until they are able to pay their premiums again. Virginia will also make efforts to collect any premium debt. Surprisingly, research indicates that even seemingly modest premiums or copayments for health care, (amounts between $1 to $5), have consistently been found to significantly reduce use of necessary services and health care outcomes for Medicaid enrollees. Even copayments as low as $1 have been shown to deter the types of preventative health behaviors that reduce long term costs. Families that would be subjected to these premiums and copayments (those living just above the poverty line) have been found to cut back on necessities and go into debt to pay for medical care.

In addition, families that are most affected by the new cost requirements are more likely to need health coverage the most. A period of illness or injury, whether short or long, can increase medical visits and prescriptions, leading to significant copayments. Thus, the costs of Medicaid copayments are likely to increase most when a person is most in need of care and could even result in a lapse in care. Losing health coverage while ill would not help a person’s prospects of maintaining employment and could lead to additional debt that may make it difficult to re-enter the program to access health coverage again. In fact, research by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that premiums and copayments tied to Medicaid are associated with increased employee absences and reduced business productivity.

Driving Up Costs for Enrollees and the State

Copayments and deductibles are sometimes grouped into a category referred to as cost-sharing, which refers to the health care costs that individuals share with another entity at the point of service. Cost-sharing usually seeks to encourage people to be cost-conscious about when and how they use health services. A common assumption among some is that Medicaid enrollees drive up health care costs by using ER services inappropriately. The Virginia budget lays out that one of the intended outcomes of imposing premiums and copayments on Medicaid enrollees is to “encourage personal responsibility and accountability related to the utilization of health care services such as the appropriate use of emergency room services.” However, numerous studies have shown that inappropriate ER visits occur at the same rate for Medicaid enrollees and people with private insurance.

Medicaid copayments alone have been shown by most studies to have little to no effect on the utilization of emergency room services. Some states have even found that collecting Medicaid copayments for non-emergency visits to the ER is more expensive to administer than the revenue collected. All of these research findings indicate that copayments will not encourage the types of health care behaviors Virginia lawmakers want to see, and will actually lead to worse health decisions and additional costs for all parties.

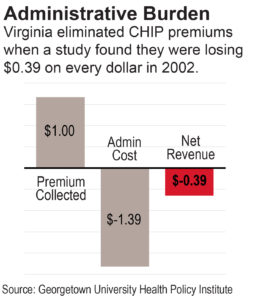

Waiver Provisions Will Increase State Administrative Costs

States have found also that premiums and copayments for Medicaid tend to generate insignificant amounts of revenue, often not even enough to outweigh the significant administrative costs. Adding premium and copayment requirements create more work and complexity for those in charge of implementing Medicaid. Updating systems to require and track premiums and copayments, along with hiring staff to monitor these systems is expensive. Other states have spent tens of millions of dollars to implement tracking systems for Medicaid premiums and copayments. Because Medicaid premiums in Virginia will vary based on each person’s income, tracking the payments and updating requirements as incomes change will be an intensive process that will require significant resources.

The cost of building the infrastructure to track premium payments may very likely exceed the amount collected. In 2002, Virginia abandoned the implementation of premiums in its Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), known as FAMIS in Virginia, due to the high costs of administration relative to the revenues collected.

In Arizona, the state found that administrative programs would cost four times the amount the state could potentially collect from premiums on Medicaid. Arizona further calculated the cost of tracking Medicaid copayments and deductibles, and found it would cost the state at least double the amount it would take in from these payments to simply track them. This shows that cost-sharing schemes tied to Medicaid are not about low-income people paying a share of their health care — these efforts turn out to be much more like punitive measure that end up restricting access to care.

There will likely also be other costs for Virginia’s state budget. When people don’t access care through Medicaid, that doesn’t mean they disappear from the health system or that there are budget savings to the state. In fact, higher Medicaid enrollment is expected to reduce the number of state dollars needed for health care by bringing more federal dollars into the system. Virginia state agencies estimate that covering more than 300,000 Virginians under Medicaid expansion will save the state $355 million in the first two years alone by reducing state-paid costs such as care for low-income uninsured people by state teaching hospitals and stop-gap services for individuals with mental illness. Yet these savings may be lower if Virginia imposes premium and copayments on near-poor families. Premiums and copayments have been shown to prevent Medicaid enrollees from accessing prescription medication and preventative care, which then leads to higher costs later when an enrollee’s health deteriorates and they need more expensive services. When Oregon increased Medicaid cost-sharing, use of services declined, but cost did not. People stopped seeking as much preventative services and expensive hospital services increased.

Moving Forward

The General Assembly has directed the state to apply for a waiver to impose new cost requirements on Medicaid enrollees, so Virginia has moved forward with a waiver that includes these lose-lose premium and copayment conditions. As we move forward, however, the state should make sure that it has a neutral evaluator of the program, makes the administrative costs and burdens of the program transparent and accessible for everyone to see, and documents the impact on consumers closely so that clear eyed assessments can be made as to whether these new requirements are meeting their stated goals of improving health care access and outcomes for more Virginians.