September 27, 2019

Virginia COMPASS Program Leading State Down The Wrong Path for Health Care

Throughout, we use the term “work reporting requirement” rather than “work requirement,” which is commonly used to refer to the policy that is the focus of this brief. As we discuss in this document, most Medicaid enrollees are working, attending school, caring for a loved one, or are seriously ill. The decision to implement a large-scale bureaucratic program to oversee monthly compliance of these types of policies will certainly lead to coverage loss simply due to confusion or bureaucratic red tape. These policies largely require enrollees to navigate a system to report what they are already doing, leading to our choice in terminology.

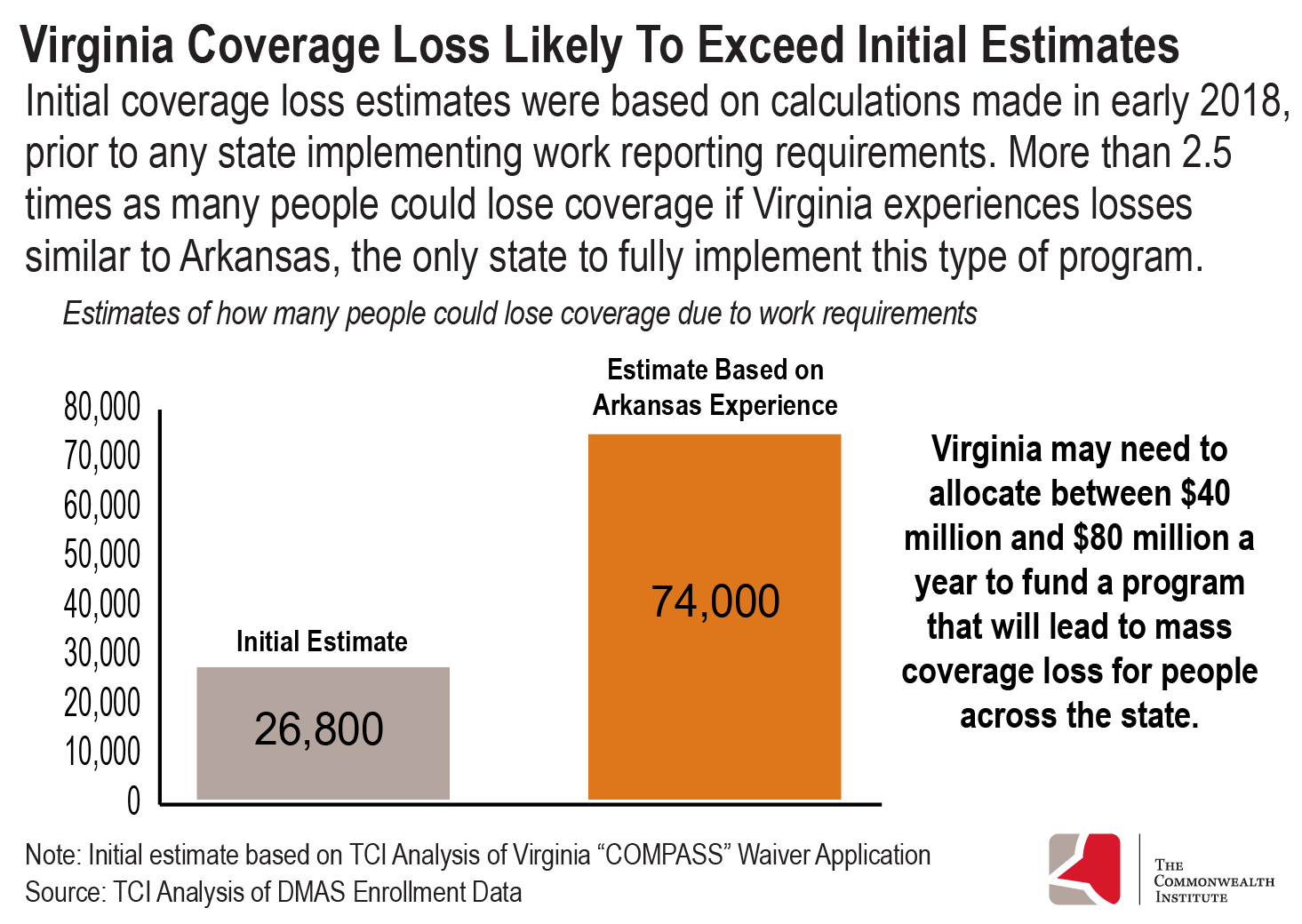

Close to 400,000 adults across Virginia now have access to comprehensive health coverage due to the state’s decision in 2018 to expand Medicaid. This marked an important step towards providing a health insurance option to families with low incomes throughout Virginia. However, the federal government could very well come to an agreement with state officials any day now that will lead to between 26,800 and 74,000 people losing health coverage in Virginia. The program, known as “Creating Opportunities for Medicaid Participants to Achieve Self-Sufficiency” (COMPASS), will negatively impact families with low incomes, especially those newly eligible for Medicaid. That is because, as part of the program, the state will soon be able to take away health coverage from people who do not meet the state’s work reporting requirement, including those who get caught up in the red tape of reporting their hours. The imposition of a work reporting requirement, along with monthly premiums for some of Virginia’s Medicaid expansion population, will cause substantial harm to the progress we have made.

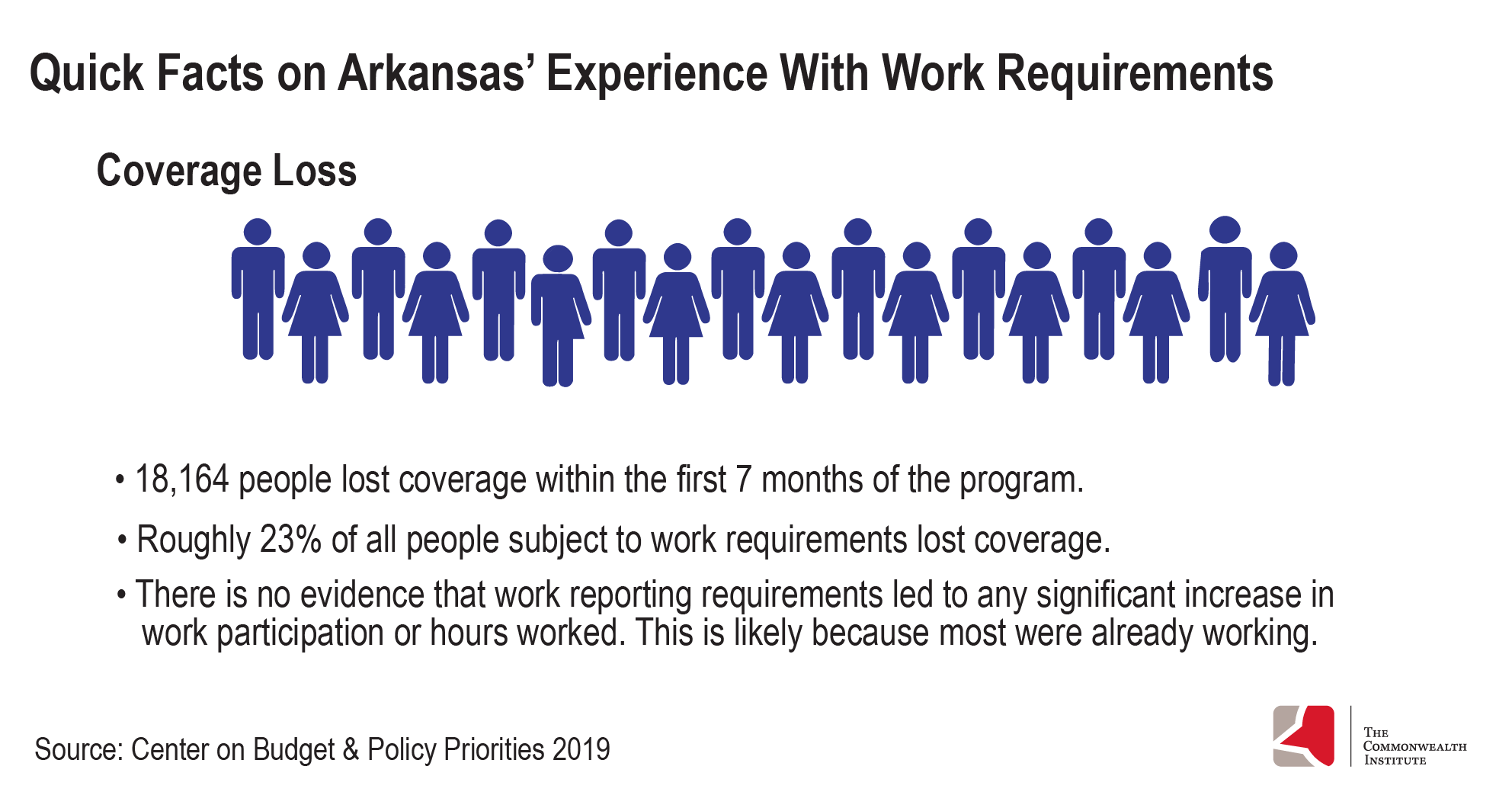

Arkansas was the first state to impose a work reporting requirement for Medicaid, which resulted in over 18,000 people — 23% of the population subject to the requirement — losing coverage in the span of just seven months.1 The policy, while not being enforced currently due to a recent court decision against it, drew fierce national criticism as stories of working individuals losing coverage as a result of Arkansas’ work reporting requirement made national news.

A growing body of evidence highlights the negative outcomes of these policies, and Virginia lawmakers should seriously reconsider moving forward with COMPASS, and instead, consider alternatives that maintain coverage and expand work supports for families with low incomes.

The Path to Expansion

At a political impasse regarding the state budget in June 2018, lawmakers who were initially resistant to expand health coverage through Medicaid agreed to move forward only if there was a work reporting requirement that accompanied it. As a result, corresponding language was added to the biennial budget as part of a deal to expand Medicaid.

Virginia first submitted an amendment to the state’s Medicaid plan to expand health coverage for adults with income up to 138% of the federal poverty level (roughly $29,400 for a family of three) within the allowable guidelines of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) approved this request within the required decision window of 90 days, with coverage to begin on January 1, 2019. At the same time, state budget language instructed the Department of Medical Assistance and Services (DMAS) to apply for an 1115 waiver to impose a work reporting requirement — which cannot be done through a state plan amendment — and monthly premiums on some of the state’s Medicaid population.

An 1115 waiver allows states to receive federal funds for experimental programs that are likely to “assist in promoting the objectives of [the Medicaid program].”2 In 2017, the Trump Administration issued new criteria by which it would evaluate whether 1115 waiver applications meet this statutory requirement. In January 2018, the Trump Administration took a step further, and issued unprecedented guidance that would allow states to impose a work reporting requirement as a condition of Medicaid coverage.

Before CMS could consider Virginia’s 1115 waiver, the ACA required a public comment period at both the state and federal level — roughly 1,700 and 1,800 public comments were submitted, respectively. The overwhelming majority of these comments raised concerns about creating additional barriers to health care and the coverage loss that would occur because of the work reporting requirement.

Success So Far

Virginia’s Medicaid expansion has had encouraging results. Over 320,000 adults have enrolled in Medicaid in the first 11 months of enrollment for those newly eligible, from November 1, 2018 through the end of September 2019.3 Many of these newly covered individuals were enrolled through strong initial outreach tactics. In addition to high public demand for health coverage, methods such as automatically enrolling or expediting the enrollment of certain people, such as parents of children already enrolled in Medicaid, by DMAS and outreach by partner organizations are credited with this success.

Not only has enrollment been strong, but research has shown that the use of health services by the expansion population is strong as well. As of September 6, 2019, more than 256,900 expansion enrollees had visited a health care provider, filled a prescription, or accessed some other health care service.4 Strong enrollment and high utilization make it clear: Medicaid expansion is working, and meeting the demand for high-quality, comprehensive health coverage for individuals and families across Virginia. Expanded access to coverage has also increased the ability to diagnose and manage long-term illnesses. Many new enrollees have chronic diseases for which they can now access treatment, including 32,000 enrollees with hypertension, 20,000 enrollees with diabetes, 18,000 enrollees with a substance use disorder, 30,000 with a serious mental illness, and 3,300 enrollees with cancer.5

Without enrollment data broken out by race, it remains to be seen how expansion is affecting communities of color. However, new national evidence shows that access to Medicaid, and Medicaid expansion in particular, can improve racial disparities in the care of cancer patients, for example. Black patients diagnosed with advanced cancer before the ACA were 4.8 percentage points less likely to start treatment within 30 days of being diagnosed. Now, in states that have expanded Medicaid, Black adults are accessing early treatment at nearly the same rate as their white counterparts.6

Women have greatly benefited from expansion. As of late September 2019, 59% of all expansion enrollees have been identified as female.7 This coverage is especially important for Black mothers, who are at higher risk of death during and after childbirth. With a statewide focus on closing maternal mortality disparities for Black mothers by 2025, Medicaid expansion could be a great asset in this initiative as more women will receive ongoing care prior to and after pregnancy.

Prior to expansion, pregnant women up to 205% of the federal poverty level (FPL) were only eligible for Medicaid coverage from pregnancy to two months after the end of pregnancy. Thanks to expansion, many new mothers will continue to have access to coverage even after their two-month postpartum coverage ends. Furthermore, DMAS and the Department of Social Services have implemented an expedited enrollment process for expecting mothers applying for Medicaid, which will result in more women receiving access to health care sooner.

Read more: Arkansas’ Experience with Work Reporting Requirements: A Cautionary Tale

What We Stand To Lose

Instituting a work reporting requirement threatens the success of Virginia’s expansion of Medicaid. Initial estimates from the state’s 1115 waiver application suggest that around 22,750 people stand to lose coverage8 due to implementing a work reporting requirement with additional coverage loss for roughly 4,100 people due to not paying monthly premiums.9 That is a projected 8.5% loss of coverage in the first year and beyond for the expansion population.10

Virginia’s original estimate is extremely conservative, because it is based on calculations made prior to any state having implemented a work reporting requirement to access health coverage through Medicaid. According to the waiver application, Virginia’s estimates mostly relied on state calculations from February 2018,11 yet Arkansas did not begin implementing its requirement until later that year, in June 2018. Incorporating the real world experience of Arkansas is a vital step toward understanding the full impact that a work reporting requirement would have on people in Virginia.

Virginia’s work reporting requirement shares many high-level similarities with Arkansas’, including an 80-hour monthly threshold and a three-month window before suspension of coverage. Given these factors, approximately 74,000 adults in Virginia could lose coverage if Virginia has a similar experience to Arkansas, in which 23% of the target population lost coverage.12 Even this high estimate could be conservative because it does not consider coverage loss due to monthly premiums and only considers coverage loss to people who gained coverage through expansion.

It appears that Arkansas’ experience is not an anomaly. New Hampshire recently put a halt to its work reporting requirement — one of the strictest proposed — after just one month, upon learning that 40% of the state’s total Medicaid expansion population was on track to lose coverage.13 So far, all experiences show that the policy is fundamentally broken and cannot be executed without thousands of people losing access to health coverage.

There is an increasingly likely scenario that the state of Virginia will have to pay tens of millions of dollars to implement the program, essentially using state funds to kick individuals off of health coverage. Recent reports suggest that Virginia state officials and CMS are at an impasse over federal funding for employment supports. Early estimates suggest that the state may need to allocate between $40 million and $80 million a year to execute the program to fidelity. Along with the state cost of implementing the program, increasing the number of uninsured people in the state would increase indigent care costs throughout the state. That money could be better spent on a non-punitive work support program that could assist families without the fear of coverage loss being held over them. Regardless of funding structure, work reporting requirement policies are fundamentally flawed and can not be executed without serious harm done to families with low incomes.

While it is difficult to say with certainty the exact impact a monthly work reporting requirement would have on coverage loss in Virginia, it is clear from not only the state’s own estimate but also from other states’ experiences, that tens of thousands will likely lose health insurance coverage in Virginia.

Read more: Virginia’s COMPASS Program, A Misguided Solution

A Work Reporting Requirement Impacts Real People

People who receive health coverage through Medicaid already face many barriers to employment. These barriers can include lack of educational attainment, lack of access to job opportunities and resources to find jobs, and greater incidence of physical and mental health concerns. Adults enrolled in Medicaid and likely to be subject to a work reporting requirement were more likely than those who were exempt and those who were privately insured to report multiple chronic health conditions, lack of household internet access, and limited transportation access, according to a 2019 study by the Urban Institute.14 These barriers may be the reason that, while most nonexempt enrollees (61.6%) worked during the year prior to the study, fewer than 1 in 6 worked at least 20 hours per week for all or nearly all weeks. Issues related to the labor market or nature of employment (e.g., difficulty finding work, restricted work schedules) and health issues were the most common reasons nonexempt enrollees reported for not working more. These factors may be particularly true for people living in rural areas of Virginia where reliable cell phone and internet coverage can be difficult to come by.

Although we do not have Medicaid expansion enrollment numbers broken out by race, we can assume that Black and Latinx communities in particular will be harmed by these policies. Due to historical and present-day factors such as systemic racism, educational inequities, and barriers to generational wealth, Black and Latinx individuals in Virginia are overrepresented in poverty and, therefore, more likely to be eligible for programs such as Medicaid. As a result, this group may be more likely to be subjected to a work reporting requirement.15 Coverage loss in communities of color due to a work reporting requirement will increase current inequities in health care access, coverage, and outcomes.

These systemic barriers to work cannot be addressed without well-funded and thoughtful approaches to supporting Virginia’s families with low incomes — and health coverage without additional barriers is critical to that support. Having health coverage has been found to bolster employment. A University of Michigan study (conducted prior to Michigan receiving approval to implement a work reporting requirement) found that 69% of enrollees reported doing better at their job due to Medicaid’s health coverage, and 55% of enrollees who were out of work at the time of the survey reported that Medicaid coverage made it easier to search for employment.16 Taking away coverage from individuals who are underemployed or meeting the hourly threshold during a given month, but may have difficulty reporting their hours, can make it much more difficult for individuals to prosper.

An Opportunity…

Despite the advanced negotiations with CMS regarding the COMPASS program, lawmakers should consider the following opportunities in the upcoming legislative session:

- End the work reporting requirement. There is still an opportunity to do away with the work reporting requirement completely through budget or legislative action. Members of Virginia’s legislature could consider removing the budget language requiring Virginia to implement a work reporting requirement for Medicaid enrollees. Michigan’s 1115 waiver to impose work reporting requirements — which has already been approved by CMS — includes specific instructions on how the state can terminate its work reporting requirement. Virginia would not be the first state to not move forward with a work reporting requirement despite advanced negotiations with CMS. For example, Maine rejected the terms of its work requirement waiver, and is therefore not implementing it. In a letter to CMS announcing the decision, the governor noted that, “Maine believes that providing appropriate education opportunities and vocational training along with critical health care, is the most effective way to lift people out of poverty.”17

- Expand employment supports. If the intention of Virginia’s legislature is to help connect individuals with low incomes to employment, there are ways to design a program to be non-punitive and, instead, invest more in job and education supports. Behavioral science research finds that such programs can empower and support families during hard times by providing well-funded supports without the risk of losing crucial health coverage. This is particularly important for people who may work seasonally or in the “gig” economy without set hours. Hiring and positioning program staff to be a supportive ally instead of a punitive figure is not possible if health coverage is contingent on meeting a certain threshold for work. Any work support that is provided should be easily accessible, especially for people of color, with targeted outreach provided by program staff. False narratives or stereotypes about individuals who receive assistance can be a deterrent to accessing these supports and are further complicated by other cultural narratives, specifically racism. Communities of color may have experiences with federal and state programming, such as previous application denial or fear of the federal public charge regulations, that may deter them from pursuing these supports. Thus a thoughtful program design sensitive to these experiences could increase enrollment, use of supports, and positive outcomes.

Other states are recognizing the harm that monthly work reporting can have. In Montana and New Hampshire, lawmakers instituted guardrails that give the state a chance to review and evaluate the impact work reporting requirements are having on coverage. Through legislation, Montana lawmakers declared that if more than 5% of those currently enrolled in Medicaid lose coverage due to the work requirement, an audit will be conducted to consider how the work reporting requirement is being implemented. In New Hampshire, state law allows the Medicaid agency to suspend its work reporting requirement if the state had “the inability to communicate verbally and in writing and directly counsel all members who are mandatory for the requirement and not already exempted.”18 In July, New Hampshire’s Medicaid agency suspended its requirement, a month before nearly 20,000 beneficiaries would have lost coverage. Despite its various outreach activities, New Hampshire’s Medicaid agency failed to reach 20,000 out of the 50,000 people potentially subject to the work reporting requirement.

Still, these are attempts to lessen the impact of what has been proven to be bad public policy. Virginia deserves a proactive solution to ending the threat of these policies.

Ongoing Legal Issues of Work Reporting Requirements

Legal battles have halted the implementation of work reporting requirements in Kentucky, New Hampshire, and Arkansas. U.S. District Judge James E. Boasberg ruled that the approval of these work reporting requirement policies were “arbitrary and capricious,” with the federal government failing to adequately consider how people accessing health coverage through Medicaid would be impacted by these policies.1 It appears that any state considering a work reporting requirement is likely to face litigation on the same grounds and with the same judge. This process would likely cost the taxpayers in order to litigate.

Conclusion

Despite the ongoing setbacks for the implementation of work reporting requirements in court, Virginia is currently moving forward with its own iteration. Virginia’s work reporting requirement will likely result in anywhere from 26,800 people to 74,000 people losing coverage, if we have an experience similar to Arkansas. The research and findings from other states makes clear that work reporting requirements have fundamental flaws that cannot be fixed, and will not result in increased employment opportunities. The purpose of the Medicaid program is to provide comprehensive health care to families and individuals with low incomes. A work reporting requirement runs counter to this goal, and this has been the basis of court decisions which halted work reporting requirements in other states. State leaders should reject the imposition of a work reporting requirement on people in Virginia’s Medicaid program. If the state continues down the path of implementing the COMPASS program, the health — both mental and physical — and financial stability of thousands of families with low incomes in Virginia will be in greater jeopardy.

More from this report:

Appendix: Potential Loss of Coverage by Locality (table)

Arkansas’ Experience with Work Reporting Requirements: A Cautionary Tale

Virginia’s COMPASS Program: A Misguided Solution

Endnotes

- Wagner, J., “Commentary: As Predicted, Arkansas’ Medicaid Waiver Is Taking Coverage Away From Eligible People,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), Jun 2019

- 42 U.S. Code § 1315. Demonstration projects, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1315

- “Expansion Dashboard,” as of Sep 20, 2019, Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS)

- “DMAS Update,” from Director of Virginia DMAS presentation to House Appropriations Committee, Sep 2019

- Ibid.

- Adamson, B.J.S., Cohen, A.B., Estevez, M, et al., “Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion impact on racial disparities in time to cancer treatment,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2019

- “Expansion Dashboard,” as of Sep 20, 2019, Virginia DMAS

- TCI Analysis of “Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services 1115 Demonstration Extension Application,” Table 8 & 9, Virginia DMAS, Sep 2018

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, “Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services 1115 Demonstration Extension Application,” Footnote 7, Sep 2018

- TCI Analysis of “Expansion Dashboard,” as of Sep 20, 2019, Virginia DMAS

- Meyer, H., “New Hampshire delays, alters its Medicaid work requirement,” Modern Healthcare, Jul 2019

- Karpman, M., “Many Adults Targeted by Medicaid Work Requirements Face Barriers to Sustained Employment,” KFF, May 2019

- TCI analysis of 2017 ACS Data via IPUMS

- Tipirneni, R., Kullgren, J.T., Ayanian, J.Z., et al., “Changes in Health and Ability to Work Among Medicaid Expansion Enrollees: a Mixed Methods Study,“ Feb 2019

- Mills, J.T., “Letter to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,” Jan 2019

- “SB 290 Final Version,” Section X, Jul 2019