June 1, 2016

Weighing Support for Virginia’s Students

Virginia Lags in Providing Low-Income Students the Opportunity to Succeed in the Classroom

Virginia’s state support for students from families that struggle economically lags behind many other states and behind what research shows is needed to provide these students with the same opportunities to be successful in the classroom as their financially more secure peers.

In Virginia, the state provides about 14 to 19 percent more for each low-income student than for other students. That’s not as impressive as it might sound. Virginia’s support for low-income students is lower than the 29 percent boost provided on average by states with this support and is well behind some states that spend almost twice as much for each low-income student. Research shows it can cost two to two-and-a-half times as much to help low-income students reach similar levels of performance as students from wealthier families.

More money is needed for low-income students because they require additional services and supports, like early childhood learning so they enter kindergarten with basic skills, and additional instruction and remediation for struggling students. The schools serving these students also need to provide salaries that attract and retain the best teachers, which can be more expensive in high-poverty communities. These types of investments have been shown to be effective nationwide in improving test scores and graduation rates, and even improving adult earnings.

Many states have commissioned studies to determine how much more needs to be allocated to give all students similar educational opportunities. Virginia should review the additional cost of educating low-income students here, too. In the absence of such a study, Virginia should at least match other states. Boosting support for Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On, which provides school divisions additional money to help instruct low-income students, would put us more in line with other states and begin to bridge the divide in Virginia between the educational opportunities available to all kids, whether their families are rich or struggling to get by.

Growing Numbers of Low-Income Students in Virginia’s Public Schools

Virginia has over 512,000 economically disadvantaged students in its public schools. That’s more than four out of every 10 students. The number has been increasing dramatically in recent years – up almost 146,000 since 2008.

These students face serious challenges that can make success in the classroom more difficult. For instance, they are more likely to have distractions in their home life, such as moving frequently, hunger, and parents coping with substance abuse. Many do not have the luxury of outside resources, such as private tutoring, that students from higher-income families may receive. They are less likely to be involved in organized activities like music lessons, clubs, or sports teams that can lead to social and mental development.

The lack of resources and support puts these students on an uneven playing field when they enter the classroom. In Virginia, economically disadvantaged students underperform on standardized tests – scoring 24 to 31 percent lower on average – are less likely to graduate on time, and more likely to drop out.

To make matters more challenging, many of these students are highly concentrated in pockets of poverty within certain school divisions. For example, in Petersburg and Richmond City more than 40 percent of children are living in poverty. Similarly, in Franklin City, Danville, Martinsville, and Galax more than 35 percent of children are in poverty. This is true in the public schools as well, where upwards of 69 percent of students in these school divisions are from low-income families that qualify for free lunch.

High concentrations of low-income students is a concern because student success is highly influenced by who they are in school with. Low-income students that are in schools with mostly other low-income students don’t get the benefit of partnering with and learning from children from families with greater resources.

These schools also face challenges in attracting and retaining the best teachers. Some high-poverty schools have offered higher salaries than their neighbors to try to keep these teachers, but that strategy is not always effective because other factors such as working conditions influence teachers’ decisions. In addition, many schools can’t afford the higher salaries, since they are typically located in poor communities where local government has a more limited tax base to support schools.

All of these factors compound on one another to make it difficult for schools in high-poverty areas to provide their students with the resources they require to be successful.

Virginia Lags in its Support for Low-Income Students

The state can and should play a pivotal role in making sure all students have similar opportunity to reach their full potential. Virginia law states that “poor children are more at risk of educational failure than children from more affluent homes.” This statement acknowledges the need for targeted support. Most states, Virginia included, allocate some additional support for low-income students. Yet, the amount states provide varies drastically, and Virginia lags behind most states with this support and behind what research shows is needed.

A nationwide school finance survey found that 37 states provide additional funding for low-income students, and most of them use “weighted approaches” to allocate additional money for each low-income student enrolled in the school. On average, states with a poverty weight provided 29 percent more per low-income student, with most providing between 20 to 25 percent more. Some provide almost twice as much.

Virginia, however, falls below these numbers.

Virginia’s main school funding formula doesn’t have a single weight for the higher cost of students in poverty. Instead, the state provides a separate pool of support to compensate school divisions for the additional cost of educating low-income students. This program – called the At-Risk Add-On – provides school divisions between 1 to 13 percent more for every low-income student in their schools, based on the concentration of poverty.

This level of support is lower than what most states that take poverty levels into consideration provide.

Virginia’s support for low-income students is also spread across other initiatives, such as reducing class size, providing preschool, test preparation, and intervention and remediation for struggling students.

Even with these additional programs, the state’s estimated poverty weight still trails other states. In 2014, the total additional support Virginia provided to school divisions for low-income students ranged from 14 to 19 percent. That’s well below the average of 29 percent provided by states that make a poverty adjustment in their school-funding formulas – and these states may have additional programs to support low-income students. The difference has a tremendous impact on how much support schools receive to help low-income students. If Virginia used the average poverty adjustment, school divisions would have received $196 million to $299 million more from the state in 2014 to support the education of low-income students.

And some states allocate substantially more than the national average. Maryland provides 97 percent more per student living in poverty than for other students, a level arrived at after the state commissioned a panel of experts to estimate the additional cost of educating low-income students.

The fact is it costs substantially more to help low-income students reach similar levels of performance as students from wealthier families. Studies in New York and Wisconsin find it can cost two to two-and-a-half times as much to educate lower-income students. Other studies in California, Kansas, and Missouri find costs ranging between 55 to 64 percent more.

The bottom line is Virginia is not targeting additional support to high-poverty schools as much as other states or as much as the research shows is needed. These additional funds are essential to offer early childhood learning programs such as preschool, to attract and keep high-quality teachers in the classroom, and to provide additional instruction to help struggling students catch-up with their peers.

But there are steps policymakers can take.

Boosting Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On

One of the main programs Virginia has for supporting the educational needs of low-income students is the At-Risk Add-On, and lawmakers should increase support for it to reflect what research shows is needed.

The At-Risk Add-On was created in 1992 following the recommendations of a state commission that found the cost of educating low-income students exceeds the amount provided by the state’s basic funding formula, called the Standards of Quality (SOQ). The state created the add-on to compensate schools for this higher cost.

In the recently enacted budget, Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On provides school divisions between 1 to 13 percent more funding for every low-income student in their schools depending on the concentration of low-income students in the school division. This means Petersburg City Schools – which has the highest percentage of free-lunch students in the state – receives 13 percent more for every low-income student and Falls Church – which has the lowest percentage of free-lunch students – receives 1 percent more for every low-income student.

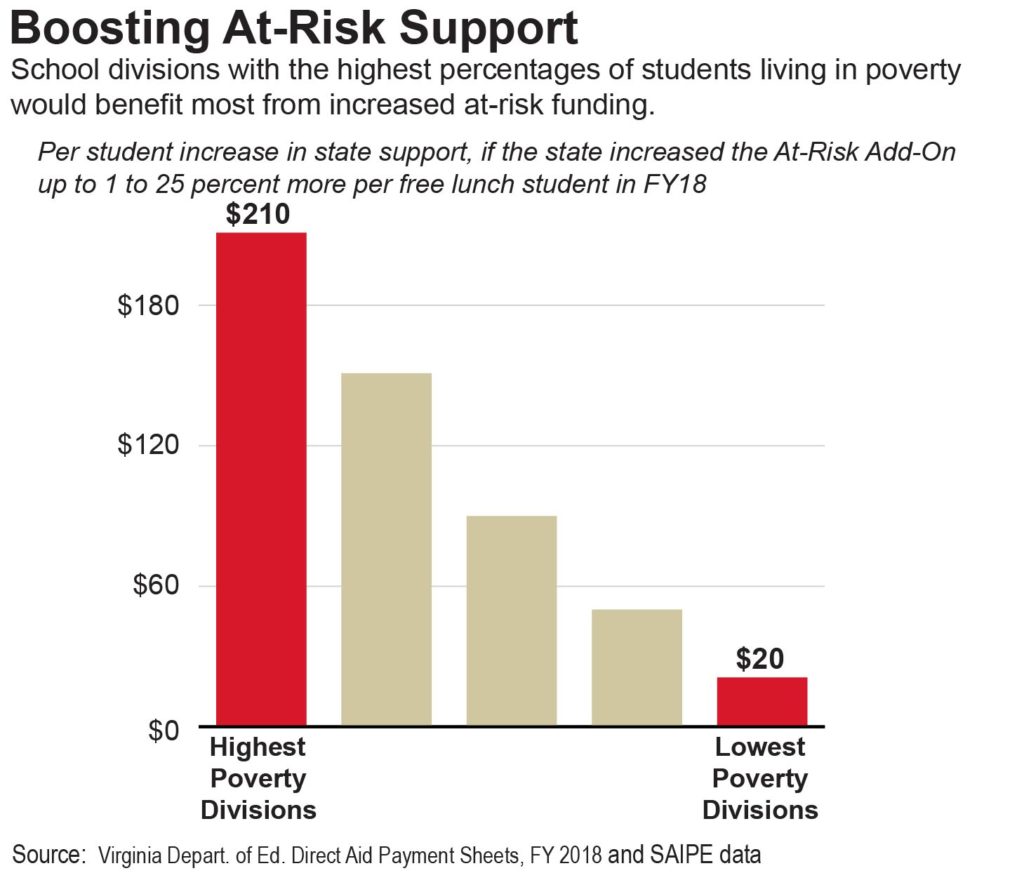

A significant improvement lawmakers could make would be to increase the range of support for Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On. For example, increasing the add-on to 1 to 25 percent more per low-income student would continue to target support to school divisions with the highest concentrations of poverty and would adjust it to be more in line with other states. Making this adjustment would almost double the state’s share of add-on funding and would increase state support in Virginia’s highest poverty schools by more than $200 per student. It also would not take away from school divisions in better off communities.

If these changes had been made during this past legislative session, Richmond City Public Schools would get over $10 million in additional state funding for fiscal years 2017 and 2018 to better support low-income students. Other high-poverty school systems would also have seen significant increases: Norfolk would have received $11 million, Newport News $10 million, and Petersburg $3 million.

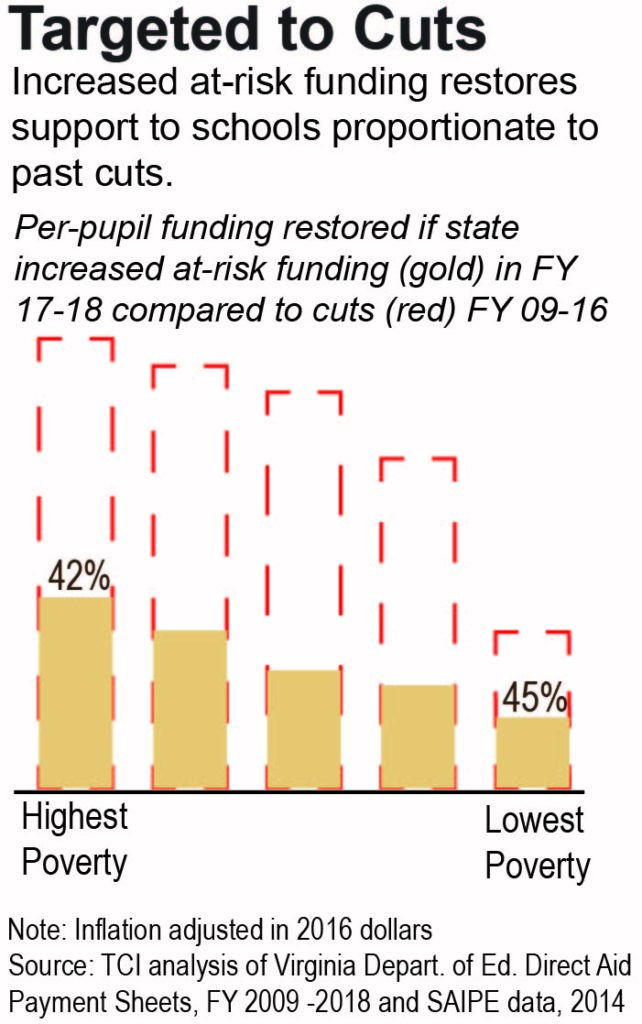

In addition, boosting the At-Risk Add-On would begin to restore support for schools in Virginia more in proportion to how they were cut during the recession. The adopted two-year budget will restore just 26 percent of the cuts in Virginia’s highest poverty school divisions on a per student basis after adjusting for inflation, while restoring 40 percent of the cuts for the wealthiest school divisions. If lawmakers had increased the At-Risk Add-On up to 1 to 25 percent per student, the restorations would be much more comparable. The highest poverty school divisions would have gotten 42 percent of their funding back and the wealthiest school division would get 45 percent back.

It seems only fair that schools should get money back similar to their cuts.

Increased Support Helps Low-Income Student Succeed

Providing support for low-income students is important because it’s in these schools where money can make the most difference. Several recent studies show that increased K-12 funding in many states during the 1970s through 2000s resulted in notably improved achievement by low-income students.

For example, a working paper released by the National Bureau of Economic Research found higher graduation rates and adult earnings for low-income students after an increase in state spending. The study found that a 20 percent increase in per pupil spending for low-income students across the 12-year period would increase graduation rates by 23 percentage points and would result in 25 percent higher earnings as an adult. A study by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth found that increased state investments in schools raised both the absolute and the relative achievement of students in low-income districts, meaning these students improved and started to catch up to students in wealthier districts.

In both studies, the effects were much less pronounced or non-existent for either non-poor students or students in wealthier school divisions. This suggests that money matters the most in education when it’s directed to high-poverty areas.

Next Steps

All of Virginia’s children deserve a high quality education, and today some kids are being left behind because of their families’ economic situation. As the state strives to build a New Virginia Economy, effectively targeting support for schools serving large numbers of low-income students would put us on a path toward greatly improving the skills of our workforce.

Instead, we are lagging behind other states and what the research shows is needed. It’s high time for lawmakers to look at the state’s funding for the At-Risk Add-On and boost support to be closer to other states so that Virginia’s education system leads the way in educating all its students, not just those living in the neighborhoods with the largest homes and highest incomes.