September 1, 2021

Labor Day Reflections on Race, Power, and Organized Labor In Virginia

In the wake of a pandemic, an economic crisis that affected marginalized communities the hardest, and a global uprising that demanded racial justice and an end to the systemic racism that has governed our country for centuries, it’s essential that we examine this country’s labor history and the ways that racism has impeded its progression. Nearly a century ago, labor unions proved to be a vital element in reviving America’s economy from the Great Depression, but thanks to decades of strategic attacks against organized labor and workers’ rights, it will be harder for unions to help in the post-pandemic recovery. Virginia’s economy is making a strong recovery, and we continue to be the top state for business. But without the power of unions, corporations and big businesses may be able to recover from the pandemic, while working people are left even further behind. Virginia has recently expanded worker rights, allowing localities to decide whether or not public sector workers should have the right to collective bargaining, but there is still work to be done. It’s time that lawmakers come together to support workers by passing laws that strengthen collective bargaining rights.

Working people in Virginia have worked together to improve their lives, but this has been often undercut by policy barriers imposed by white elite legislators and courts.

Working people have a strong history of using labor organizing and collective bargaining to improve working conditions and the economic status of millions. From fighting for the 8-hour work day, to ending child labor, to pushing employers and government officials to make workplaces safer, organized labor has tremendously improved the quality of life for almost every working American. This is especially true when it comes to combating racial wage inequality. It was in heavily unionized sectors, such as railroads, that Black workers were able to organize both economically and politically to fight for a more equitable system. Here in Virginia, this history includes innovative labor-community partnerships, like when Richmond barrel-makers who were members of an integrated trade union organized a successful consumer boycott in 1885 of the Haxall-Crenshaw Flour Company to end their use of barrels made with convict labor, and when a council of Black community leaders in Charlottesville supported a group of 28 maids at the University of Virginia Hospital who walked out in 1943 in protest of inadequate wages.

Yet today, just 4.4% of wage and salary workers in Virginia are affiliated with a union, tying with Tennessee for fifth lowest union membership in the country and well below the 15.8% share in 1964, the first year for which state data is available. Nationally, 10.8% of workers are union members, down from nearly 36% of non-agricultural workers in 1945. Unionization rates in Virginia and the U.S. are also well below those of peer nations such as the U.K. (24%) and Canada (27%).

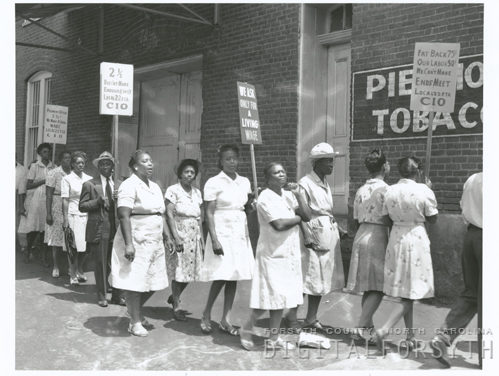

Credit: Jones, Frank. “Protest at Piedmont Leave Tobacco Company, 1946.” Photograph. 1946. Forsyth County Public Library: Digital Forsyth. https://www.digitalforsyth.org/photos/1022

Virginia’s decline in union membership is not a coincidence–– it’s the result of strategic attacks on organized labor and laws that systematically hinders workers’ ability to unionize. In 1888, just 3 years after the successful Richmond campaign, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals outlawed consumer boycotts, a ban that remained in effect until 1916. And as union strength and class solidarity began to spread across the country in the 1930s and 1940s, politicians in the South began to fear that an increase in union membership would pose a threat to the prevailing racial order, leading to anti-labor sentiments spreading amongst the Southern congressional delegation.

But this fear didn’t spread on its own. Beginning in the early 1940s, lobbyists and businessmen interested in preserving the old ways of the Jim Crow South began to collaborate in order to spread antisemetic, anti-Black, and anti-union rhetoric. Vance Muse and the Christian American Association (CAA) became the most ardent supporters of this messaging, arguing that unions would lead to power being ceded to Jewish Marxists and Black workers. Muse, an oil Industry lobbyist from Texas, founded the CAA with the backing of Southern oil companies and industrialists in the Northeast and began working to stifle union gains in the South.

Beginning in 1944, Muse and the CAA began a campaign to spread so-called right-to-work (RTW) laws across the country. By the end of 1947, 11 states had passed RTW laws, including Virginia. And, in 1946, when the only group of state employees in Virginia who were formally organized through a labor union was Black hospital workers, the General Assembly passed a resolution banning recognition of public sector unions. At the federal level, the Taft-Hartley Act ensured that no worker could be forced to join a union as a condition of employment. RTW legislation went further, granting workers the benefits of a union contract without paying the costs of dues or maintenance fees.

Today, 27 states and Guam have RTW laws. These laws have been effective in serving the purpose that Muse wanted them to–– wages in RTW states are approximately 3.2% lower than those in non-RTW states, and workers in RTW states are less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance or pension coverage, regardless of whether or not they are members of unions. It’s no coincidence that today 8 of the 10 states with the highest percentage of Black residents also have RTW laws, especially when considering the fact that Black and Latinx workers who belong to unions tend to receive higher wages, have wages that are closer to their white peers, and receive better benefits than their non-unionized counterparts.

Unions have also often excluded or sidelined Black and brown workers, harming the very workers they seek to support

It’s important to acknowledge that unions, like all institutions in America, have a history of racially discriminating against Black and brown workers. From refusing admission, to segregating local chapters, to excluding people of color from elected and appointed policy-making positions, unions of the past and present have done a less than stellar job of ensuring that all workers are protected. Many of the gains brought about by the New Deal were meant to be experienced by white workers, and any benefits felt by workers of color were a side effect. Farmworkers and domestic workers were barred from unionizing in the 1930s for the same reason that RTW laws gained popularity in the 1940s––New Dealers feared that they would upset Southern elites by empowering Black and brown workers who occupied these jobs. Working people of all races have been harmed as white laborers have too often allowed themselves to be pitted against workers of color who wished to join them to fight for better working conditions. But we know that when workers join together, great progress can be made. In 2008, for example, Black and Latinx workers in North Carolina overcame intimidation, firings, and immigration raids to organize the largest Smithfield Food hog slaughterhouse. Together, Smithfield workers secured better working conditions for all of their workers––regardless of race. In remembering labor history, it’s important to remember who has typically been sidelined from experiencing the progress that unions have made, and make sure that today’s and tomorrow’s organizing is not repeating the errors of the past.

Today, we can dismantle policy barriers and allow working people to join together in unions to build more equitable workplaces and communities

Credit: Vertical Sandbox

As we remember this history on Labor Day, it’s important that we also look ahead to ways that policymakers can dismantle the barriers facing working people, especially working people of color, that were imposed through past policy choices. Virginia has already made progress. Beginning in May of this year, localities were given the opportunity to pass ordinances to allow local public employees to engage in collective bargaining over wages and working conditions. Currently, local public employees in Virginia are paid 29.9% less than private-sector peers with similar levels of education and experience—a pay penalty that more often hits Black workers and women, who are more likely to be employed in local public service. States where public employees are allowed to collectively bargain have smaller pay penalties, and clear standards provided by unionization particularly help Black and Latinx workers. It’s time that localities allow their workers to collectively bargain, should they choose to do so.

On a statewide level there is also still work to do. Virginia is a place for innovation and economic prosperity, but as the law is written today not all Virginians get to experience this. Looking forward, Virginia policymakers should continue moving the state toward the “high road” for working people, including allowing state employees to engage in collective bargaining and address restrictive RTW laws. Evidence suggests that all workers, not just union members, benefit from strong unions that advocate for better working conditions and higher wages. Policymakers should also end the exclusion of farmworkers from basic labor protections such as the minimum wage and provide them with the ability to collectively bargain. Removing labor exemptions that exclude some of the most essential workers in the economy would allow for the most vulnerable workers to come together and organize. As we move towards an economy that works for everyone, it’s time to give workers a voice by recognizing their rights and strengthening their bargaining tools.

Category:

Economic Opportunity