July 19, 2023

Richmond’s Tradition of Black-led Labor Organizing: Then and Now

The City of Richmond is the heart of power and politics in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As the state capital and the former capital of the Confederacy, what happens in Richmond has been historically significant to the state and the nation. This holds true both for building worker power and the attempts by corporations and politicians, threatened by worker solidarity, to suppress that power. At a time when public support of unions has reached its highest levels in decades, it is worth chronicling Richmond’s remarkable history of worker organizing in the face of these power structures.

This history is rooted in Black-led organizing campaigns and interracial solidarity that sought to uplift people at the margins. Campaigns of the past and present show how important unions are for all working people, and the threads that run through this history are essential for informing our continued efforts into the future.

Jump to Section:

Richmond labor organizing in the 1880s

Working people in Richmond were active participants in the early modern labor movement in the 1880s, relying on interracial solidarity between Black and white workers and leveraging widespread boycotts of offending businesses to improve conditions. Given the time period and Richmond’s history as the former capital of the Confederacy, the historic nature of interracial solidarity during this period cannot be overstated. This solidarity was made possible in part by coordinated pressure campaigns from local trade unions and the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, the largest association of workers in 19th-century America.

Tradespeople in Richmond had been organizing before the local Knights of Labor chapter formed. For example, the first recorded use of a boycott in Richmond occurred in 1880, when workers at Liebermuth and Millhiser Cigar Co. instituted a boycott against their employer. While labor organizations historically limited themselves to a specific trade, such as ironworkers, cigar makers, barbers, etc., by allowing anyone to join regardless of trade, the Knights of Labor revolutionized the labor movement nationwide. A few years after the first recorded boycott, Black and white workers in Richmond organized under the umbrella of the Knights of Labor with the support of the Knights’ national leadership. Though structural divisions along racial lines in the union remained, Black and white workers exerted political pressure as one. Membership boomed, and the Knights deployed campaigns against offending businesses throughout the city.

We organize the colored workers into separate assemblies, working under the same laws and enjoying the same privileges as their white brethren… The politicians have kept the white and black men of the South apart, while crushing both. Our aim shall be to educate both and elevate them by bringing them together.

Terence Powderly, the General Master Workman of the Knights, “Richmond Story: The Knights of Labor,” the valentine

In the summer of 1885, Knights of Labor, District Assembly 84 and District Assembly No. 92 focused on ending “convict labor” in the barrel-making industry. They decided to take on one of the biggest purchasers in Richmond at the time: the Haxall-Crenshaw Flour Company. The campaign went beyond just the workers at the flour mill — it relied on a broader consumer boycott of Haxall-Crenshaw flour. At one point, the Richmond Dispatch published the following notice, attributed to the mills’ manager:

“WANTED, President and Secretary of the Knights of Labor, to STOP BOYCOTTING ME, or they must take the consequences. I mean business. No fooling.”

The boycott lasted nine months before the company relented and the barrel-makers won. The use of convict labor in barrel-making ceased in the City of Richmond.

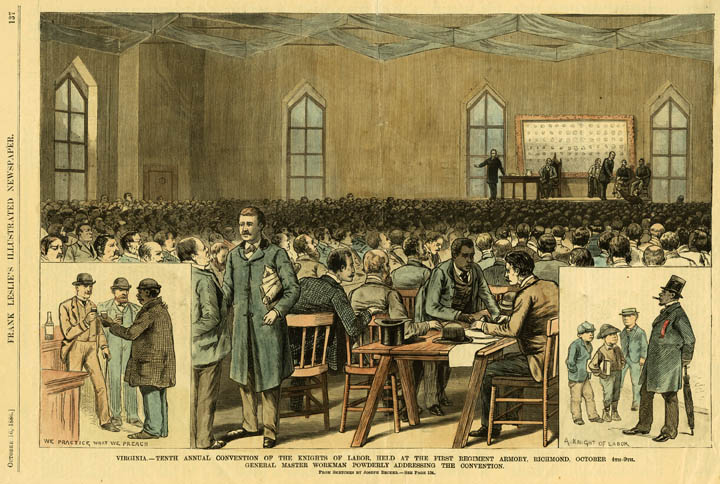

Tenth Annual Convention of the Knights of Labor held at the First Regiment Armory in Richmond, October 16, 1886 (Image: Public Domain)

The Knights also collaborated with trade-specific unions in the city. One example of this collaboration is the 1886 Baughman Brothers strike and ensuing boycotts. By 1886, the Richmond Typographical Union, No. 90 was the strongest local in the city and worked closely with the Knights of Labor. They wanted to organize against the Baughmen Brothers, the only city printing office that had not yet unionized its workforce. On February 1, union members walked out of the printing office. Four days later, the Typographical Union voted to formally boycott Baughman Brothers, and they also organized a secondary boycott of anyone dealing with the printing office. The Executive Council of the Richmond Knights of Labor District Assembly, No. 84 immediately endorsed the boycott and offered the services of its weekly newspaper, the Labor Herald.

After a brief break, the Typographical Union resumed their secondary boycott on March 5, with the Richmond Cigar Maker’s Union, No. 133 pledging their support of the action. During the initial stages of the boycott, membership in Typographical Union, No. 90 increased by 38%. As a result of the boycott, Baughman Brothers defaulted on its government contract to print the documents and proceedings of the Virginia House and Senate, after which they essentially lost their big contracts and were limited to much smaller orders. (The Typographical Union would later turn its attention to printers in Alexandria, Lynchburg, and Petersburg, helping them to organize local unions.)

Consistent with Virginia’s labor history, white elites continued to find ways to deny people their rights and suppress labor organizing. For example, white newspapers in Richmond and throughout the South continued to use racial fears to divide working people and undermine the labor movement. When the Knights of Labor held their National Convention in Richmond in October 1886, hostile newspapers focused on the actions of some racially integrated delegations – including deliberate attempts by one delegation to test the exclusion of Black people from many Richmond venues. The resulting focus by the convention delegates on the question of racial integration of public spaces meant they did not address most major planned topics, and some commentators have argued that this convention led to a loss of white southern members in the Knights. And in 1888, in response to successful labor actions like the Haxall-Crenshaw flour boycott, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals declared “that the right to boycott was ‘incompatible with the prosperity, peace, and civilization of the Country.’” Herein lies a prime example of how elite actors used their power to take away the tools of working people – particularly Black working people – who were successfully organizing to improve their lives and those of their neighbors.

Richmond’s Black labor organizing wins of the 1930s & 1940s

Richmond’s labor history rests not only on solidarity between working-class Black and white people, it also includes active solidarity among Black people across class lines, with Black college students supporting organizing by working-class tobacco workers. In 1937, young people who had attended the National Negro Congress (NNC) in Chicago the year prior formed the First Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). Among these activists were veteran organizers such as James Jackson, Helen Gray, Esther Cooper, and Edward Strong. On February 13 and 14, 1937, SNYC held their first conference in Richmond, attended by over 534 delegates from across the South representing nearly every historically Black college or university (HBCU) in the country as well as the YMCA, Girl Scouts, and Boy Scouts. SNYC’s first successful campaign organized workers in Richmond tobacco factories.

With the support of SNYC, 300 tobacco stemmers in the Carrington and Michaux plant held a strike against their employer in the spring of 1937. The workers won a wage increase, an eight-hour-day/40-hour-week, and collective bargaining recognition. After a successful first action, SNYC would later help organize anti-lynching campaigns across the South and move its headquarters to Alabama. Their successful organizing in Richmond would spark change across the city’s tobacco industry.

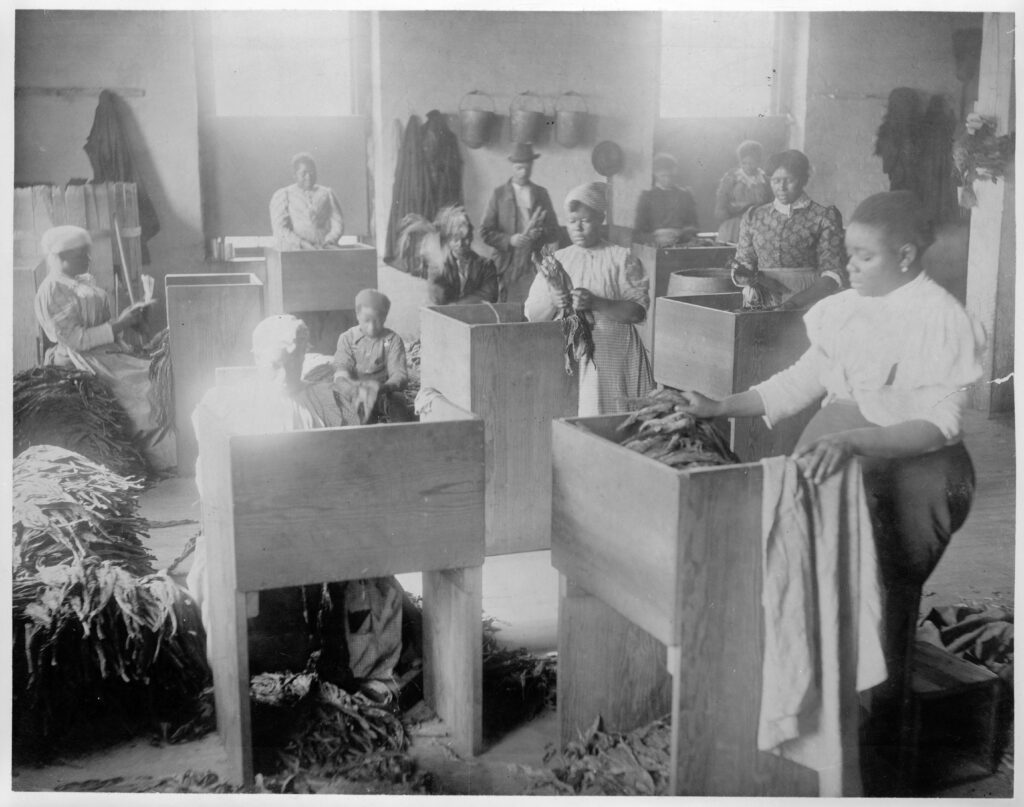

Sorting tobacco at the T. C. Williams & Co., tobacco, Richmond, Virginia. Richmond, Virginia, 1899 (Image: Public Domain)

On the heels of the Carrington and Michaux settlement, 400 Black women tobacco stemmers went on strike on May 6, 1937, at I.N. Vaughan Export Leaf Tobacco Company (herein referred to as “Export”). The workers were primarily concerned over meager wages and lousy working conditions. Thanks to past worker organizing, they could leverage a pre-established bargaining apparatus. Workers ultimately secured a contract with higher wages and reduced hours.

Later that same year, in August 1937, workers went on strike at Tobacco By-Products and Chemical Corporation. Tobacco By-Products was a major employer in the Richmond area and employed about 200 Black workers. The strike, which lasted several weeks, was successful – resulting in the formal recognition of the workers and their skill. The win also came with wage increases, paid vacation time, a 40-hour work week, and guaranteed overtime pay.

In 1938, organized workers at Export achieved the hardest-won victory yet of Richmond’s tobacco unions. Like most Black women in the tobacco industry nationwide, the Black women stemmers who worked at Export were among Richmond’s lowest paid – earning about $3 a week and often working more than 90 hours a week in terrible conditions. In addition to being cramped and working in a dirty environment, they had to wrap themselves in tobacco burlap to keep themselves from freezing during the winter months.

…preachers don’t know nothing about Hell. They ain’t worked in no tobacco factory.

Louise “Mama” Harris, The New Republic, November 4, 1940

Labor activist Louise “Mama” Harris was one of these women. Harris’ impact on labor organizing in Richmond is remarkable, especially because she was not a lifetime labor leader – formerly a child care worker, she started labor organizing in her late thirties after she entered the tobacco industry. In addition to experiencing the terrible conditions at Export, Harris had been harassed by a colleague since the day she started working at the stemmery. In 1937, six years into her employment, she heard about a union that started organizing Export earlier that week. She jumped at the opportunity to organize her workplace and brought 60 fellow Black women stemmers to the first union meeting she attended. Soon after, she helped organize hundreds of workers at Export and participated in the August 1, 1938, strike.

When they asked for volunteers to organize Export, I can’t get to my feet quick enough…And then on the first of August, 1938, we let ‘em have it. We called our strike and closed up Export tight as a bass drum…Then this scab came up with a couple hundred others and tried to break our line [of five hundred], but we wasn’t giving… a dog a bone.

Louise “Mama” Harris, The New Republic, November 4, 1940

Their 18-day strike was met with intense resistance by management and police, but public support was on the side of the workers. In a historic first in Richmond’s labor history, hundreds of white women from the local Richmond Garment Worker Union (GWU) joined the picket line. Many other Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO)-affiliated unions donated to the cause, including the Newspaper Guild, American Federation of Teachers (AFT), and the Clothing Workers of America (CWA). This show of interracial solidarity challenged the color barrier in the city.

Them cops jump salty as hell. ‘White women,’ they say, ‘white women out here parading for [Black people].’ But they don’t do nothing. Because we ain’t taking no stuff from nobody.

Bennie Harris (Louise Harris’ husband and picket captain of the August strike), The New Republic, November 4, 1940

Management even threatened to move the plant outside of the city altogether. But the union’s demands were ultimately met: higher wages, paid vacations, seniority rights, and a more streamlined dues collection system. Louise Harris contributed to the success of the action at Export in multiple ways, including securing the support of multiple labor CIOs for the strike. Her labor activism earned her the reputation as “Missus CIO” of Richmond.

Richmond labor organizing in the modern day

Successful labor organizing continues today in the City of Richmond, uplifting workers of all racial and ethnic backgrounds in both the public and private sector. The last few years have been especially active due to the General Assembly repealing Virginia’s ban on public-sector bargaining at the local level in 2020.

Crowd gathered outside MLK Middle School before a school board meeting to support collective bargaining rights for Richmond Public Schools staff, December 6, 2021 (Photo credit: Richmond Times-Dispatch)

On December 6, 2021, Richmond Public Schools staff, with the assistance of the Virginia Education Association, organized successfully to become the first school district in the state to win a collective bargaining ordinance. A year later, in another historic first, the Richmond Education Association’s four bargaining units (teachers, instructional assistants, care and safety, and food and nutrition employees) became the first in the state to ratify union contracts in December 2022. The contracts provided significant pay raises for each unit and other needed benefits such as a minimum of three unencumbered planning periods per week. The Richmond School Board still has to approve the contracts.

This moment in time is a time that we can all look at and say finally… the education profession in Richmond is getting the respect that is due to [it].

Charlotte Hayer, teacher at Richmond Community High School, Richmond Times-Dispatch, december 15, 2022

On January 13, 2022, The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported that Richmond City public workers began organizing with the assistance of Service Employees International Union (SEIU) 512 to pass a broad and inclusive collective bargaining ordinance through City Council. After months of public hearings and meetings with city leaders, they won their collective bargaining ordinance that summer. The ordinance passed by the council formed five different bargaining units: police, fire and emergency services, labor and trades, professional, and administrative/technical workers. On February 16, 2023, the administrative and technical city employees as well as professional workers announced their union election filing to join SEIU 512 Virginia. In a united press conference with SEIU 512, the workers from the labor and trades unit also announced their election filing to join Teamsters Local 322 that same day. Together, the three units make up about half the city’s workforce.

Public-sector workers employed by state universities are organizing as well. On April 26, 2021, despite the prohibition on state-level collective bargaining still in place, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) student workers and staff formed a wall-to-wall union under the umbrella of United Campus Workers (UCW). Two days later, the VCU Provost emailed the deans of all colleges with instructions to cut adjunct hours immediately. UCW-VCU quickly responded by engaging with the VCU Faculty Senate, which resulted in a shift away from the intended cuts and instead increased benefits for staff. One of the union’s newest campaigns, #NoVCULayoffs, seeks to protect educators in the Department of Focused Inquiry from potential layoffs, arguing that the department is supposed to teach students core skills. And as recently as July 13, 2023, VCU cleaners, organized under 32BJ SEIU, announced the ratification of a new contract containing multiple wins, including a $4 hourly wage increase and 12 paid days off.

How many 58-year-olds do you know making $12.24 an hour? I had to rob Peter to pay Paul, but now I can improve my credit score so I can try to get a mortgage. I can also now pay for health insurance and not lose pay to see the doctor…

Angela Arrington, VCU cleaner, discussing the 32BJ SEIU contract win

Significant organizing is also happening in the private sector in Richmond and the broader region, including factory workers, baristas, hotel workers, and call center employees. On August 10, 2021, Nabisco/Mondelez factory workers, organized under the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (BCTGM), joined their colleagues across the country in a strike against changes to pensions, outsourcing, overtime pay. Workers also expressed frustration over changes to the “Gold 80” rule, which allowed employees to retire based on age and year worked.

I was one of those people affected by [Golden 80 Rule]… I’m 50 now. I’ll be 51 next month. I would’ve been able to retire at 54. They’ve already taken one thing from me where I can’t retire now until I’m 65. So guess, what? This fight, it means a whole lot to me.

Tacella Thornton, snack-packing technician who has worked at the Richmond Nabisco plant for 22 years,

VPM, September 16, 2021

Nabisco’s parent company Mondelez announced that they reached a tentative agreement on new contracts with BCTGM on September 16, 2021. Workers voted overwhelmingly in favor of the new contract and announced the end of their strike on September 18, 2021.

In early 2022, as part of a national wave of Starbucks worker organizing, employees at five Richmond stores (Willow Lawn, Forest Hill, Huguenot Village Shopping Center, Westchester Commons, and Midlothian and Carmia Way) filed for union elections with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and won the subsequent elections. Since then, they’ve been joined by workers at the stores on Arthur Ashe Boulevard and in Carytown.

In August 2022 employees of the federal government’s largest call center contractor, Maximus, staged a picket at its Chester location in protest of low compensation and poor working conditions, including unfair attendance and bathroom break policies. The following year, on June 5, 2023, the call center employees formally went on strike. With the support of the Communication Workers of America (CWA), the workers are calling for $25 per hour, protection from unfair layoffs, and career advancement opportunities. According to the Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charges filed against Maximus by the CWA, the call center allegedly laid off workers in retaliation for speaking out about their working conditions and offered workers unlawful severance agreements.

And in September 2022, Richmond workers at the Hampton Inn Richmond-West Innsbrook hotel also announced their plans to unionize.

We are not peons. We are human beings…We need to be respected — and that doesn’t just go for me or [the people who work at] this hotel — it should be a global thing.

Marty Barnett, 72, hotel employee of 26 years, Richmond times-dispatch, September 9, 2022

Where Richmond goes from here

As Richmond residents look toward the future, it is important to remember that labor organizing is not a new or niche activity confined to a particular workplace. People who are fighting for labor rights today are continuing the tradition set forth generations ago. Richmond’s strong history of labor organizing in the face of incredibly hostile conditions helped uplift the city’s most marginalized workers and changed their communities for the better. These campaigns, driven by Black workers in different industries, relied on interracial solidarity to uplift the city’s working people and improve working conditions.

This history shows that broad support of worker organizing – whether in the public or private sector – is critical to transforming the lives of city residents who need it most. Workers then and now want the same timeless things: to be paid a living wage, to have quality working conditions, and to be heard on the job. By supporting worker organizing in the city, Richmond can help deliver exactly that and model for the state what it means to be a great place to work.

Category:

Economic Opportunity