January 14, 2020

State Tax Proposals Would Make Virginia’s Tax System More Fair

The 2020 General Assembly session offers an opportunity for state lawmakers to substantially boost investments into critical areas while also making Virginia’s tax system more fair. That includes legislation to support working families throughout the state through a stronger Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) as well as a proposal to automatically adjust the state tax code for inflation. Several proposals would also shore up the state’s tax base to make sure the wealthiest households and large corporations pay more of their share in state taxes.

Public investments help to support communities across our state. State resources provide funding for public schools, health care, transportation, and more. However, Virginia’s current state and local tax system has two major challenges. First, the current revenue system is inadequate, which means it’s not generating the revenues necessary for public investments. For example, the state’s K-12 public schools, colleges, and universities continue to face funding challenges despite ongoing growth in the economy. Second, Virginia’s state and local tax system is upside-down. On average, the highest-income people in the state pay the lowest in state and local taxes as a share of their income. To address both issues, lawmakers should design tax policies that reduce taxes on families with low and moderate incomes, while asking the wealthiest households and large corporations to pay their fair share – including by closing some loopholes in the current tax system.

Refundable Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

One proposal in the House (HB 1435) would strengthen Virginia’s existing EITC by making it refundable. The EITC is a commonsense policy tool to support working families with low to moderate incomes. Over 600,000 working families in Virginia currently receive the federal EITC, which helps families to put food on the table, keep up with utility bills, and afford other necessities. Research shows the federal EITC is one of the most successful tools at lifting families above the poverty line, which is about $21,300 for a family of three.

Thirty states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have created their own versions of the EITC to supplement the federal credit. Working families in Virginia who claim the federal EITC can also claim a state EITC that equals 20% of the value of their federal EITC.

However, Virginia’s EITC is “nonrefundable,” which means the state imposes restrictions that prevent many families from receiving the full value of their state EITC. The restriction adds up to over $200 million that working families across Virginia miss out on each year, and these limits particularly impact Black and Latinx families.

Adopting combined reporting

Two proposals in the House (HB 739 and HB 1109) and one in the Senate (SB 756) would adopt a corporate tax reform known as unitary combined reporting. This policy would end an unfair advantage that allows large corporations to reduce their state tax bills.

Under Virginia’s current system, large multi-state corporations can use accounting maneuvers and exploit weaknesses in the tax structure to reduce their state taxes. Corporations can shift profits to states that tax those profits at lower rates – or not at all. For example, a manufacturing corporation could set up subsidiary companies in low-tax states as suppliers of their factory inputs. The parent company could then pay their subsidiaries an artificially high price for those inputs, which would then get deducted as a business expense. The end result would be a reduced tax bill.

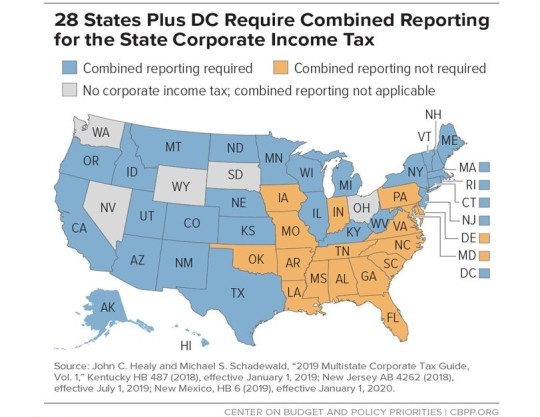

In response, 28 states and D.C. have passed combined reporting laws to require corporations to add up all of the income from the parent company and most or all of its subsidiaries. Many common tax avoidance strategies are negated.

This reform would also end a tax advantage that locally-based corporations without out-of-state subsidiaries do not get. In terms of tax fairness, this policy places businesses on a more level playing field and makes sure large corporations pay more of their fair share in taxes. In addition, for many of these large corporations, they already adhere to combined reporting requirements when filing taxes in one of the other states that has adopted this policy, so this will not be a new practice for them.

The official “Fiscal Impact Statement” has not yet been published for these three bills. According to previous estimates, Virginia likely would gain between $80 million and $165 million a year in additional revenue from this reform.

Restoring Virginia’s estate tax

HB 736 and SB 637 would restore Virginia’s estate tax and make sure that the wealthiest estates pay their share of state taxes.

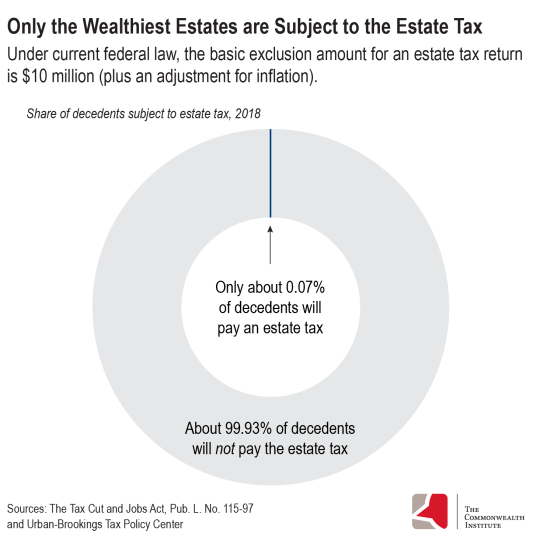

State taxes on inherited wealth are a powerful tool to build shared prosperity. These taxes often take the form of estate taxes modeled on the federal estate tax and include large exemptions so the tax only applies to the wealthiest estates. (An estate is the value of a deceased individual’s cash, securities, real estate, business interests, and other assets, minus the value of mortgages and other debts, estate administration expenses, and property passed to surviving spouses and qualified charities.) Under the 2017 federal tax law, only estates valued at more than $10 million (plus an inflation adjustment) would be subject to the estate tax. For 2020, an estate tax filing is required for estates with combined gross assets and prior taxable gifts in excess of $11.58 million. According to estimates from the Tax Policy Center, estate tax returns will only need to be filed for 0.15% of decedents, and only about 0.07% will result in any federal estate tax. The state estate tax proposals also include additional exemptions for closely held businesses or working farms.

Before July 2007, Virginia had its own estate tax. By eliminating the tax, state policymakers have decided to allow substantial amounts of investment income to escape state taxation entirely. That’s because investment income from “capital gains” is only taxed when the gain is “realized” (e.g., selling a stock or other investment). However, one big exception applies to inherited assets, where decedents’ gains are “stepped up,” which in practice allows wealthy people to pass on assets to their heirs free of capital gains tax. A state estate tax would partially counteract this loophole for large estates when assets are passed onto heirs.

Taxing wealth would also address the racial wealth divide. Recent data show that white households have an average net worth of $127,390, compared to $19,790 for households of color. The divide has emerged after years of violence, exclusion, and racist policies against Black, Latinx, Native American, and Asian American communities, as well as other communities of color. Inheritance and wealth are linked, and for white households, their higher likelihood of receiving an inheritance and the larger average value of inheritances received may explain part of these gaps. Taxing a portion of the wealth of the largest estates and boosting funding for public investments would help to build greater opportunity more broadly.

Similar proposals from recent legislative sessions were estimated to increase state revenues by about $69 million per year. HB 736 and SB 637 specify that the revenues would be used on health care funding.

Indexing key tax provisions to inflation

HB 735 would automatically adjust the state standard deduction, personal exemptions, and tax brackets each year to account for changes in inflation.

Major provisions of Virginia’s individual income tax system hadn’t been substantially updated in many years until last year’s increase to the state standard deduction. For example, the state’s personal exemption has been set at $930 since 2008, and the additional exemption for blind or elderly taxpayers has been $800 since 1988. In addition, the state’s income tax brackets were set in legislation enacted in 1987 and phased in through 1990. The top bracket begins at taxable incomes over $17,000. That means a person with taxable income of $17,050 would pay the same marginal state income tax rate as a person with $1 million in taxable income.

By indexing these provisions to inflation, these state tax features would be automatically updated without the need for repeated legislative action. Under the status quo, a larger and larger share of income becomes subject to higher state tax rates, simply through inflation, which can have a significant impact on the ability of families with low and moderate incomes to provide for their families. Many states with an income tax have provisions to make these automatic adjustments to their state standard deductions or state personal exemptions.

Virginia’s state tax system needs to be updated so that the state has sufficient revenues to meet its funding commitments. At the same time, Virginia lawmakers also have policy tools available to increase public investments while also addressing our upside-down tax system. The legislation summarized above would represent a meaningful step toward these goals.

Category:

Budget & Revenue