July 24, 2018

A Closer Look: The Contributions of Black Immigrants to Virginia’s Economy

Black immigrants living in Virginia are an important part of the state’s economy and future. A majority of working-age Black immigrants are employed; many have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and most have lived in the United States for many years. Taking a deeper dive, there are significant differences as well as shared experiences among Black immigrants from different regions, non-Black immigrant Virginians, and U.S.-born Black Virginians.

This paper takes that closer look and documents the significant cultural and economic contributions Black immigrants make to the commonwealth as well as the ongoing barriers they face.

The Diverse Origins of Black Immigrants

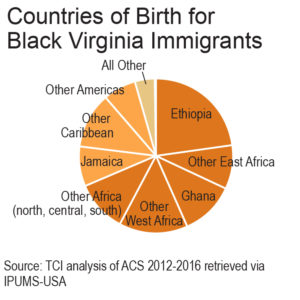

Black Virginians who are immigrants to the United States moved here from a wide range of countries. About 113,000 foreign-born Black individuals called Virginia home in 2016, up from about 86,000 in 2007. That is 11 percent of all foreign-born Virginians and 7 percent of all Black Virginians. Virginia is home to over 25,000 Black Ethiopian immigrants, who make up more than one in five of all Black immigrants in the state. Ghana is the next most common place of birth for Black immigrants in Virginia (12,800), followed by Jamaica (9,300). Between 3,000 and 5,000 Black immigrant Virginians were born in Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Haiti, Sudan, and Trinidad and Tobago (in descending size order). At the regional level, about one-third of Black immigrants in Virginia were born in East Africa, one-quarter in West Africa, and one in five in the Caribbean (including the West Indies).

This mix is very different from the United States as a whole, where the Caribbean is the place of birth for nearly half of Black-identified immigrants, and Jamaica and Haiti are the most common birthplaces.

More than two-thirds of the state’s Black immigrants live in Northern Virginia. Another 14 percent live in the Virginia Beach/Hampton Roads metro area, and 9 percent live in the Richmond metro area. Smaller numbers of Black immigrants also live in smaller metro areas in Virginia, particularly the Roanoke area, and in rural Virginia.

Long-term Residency Shows Commitment to Life in the U.S.

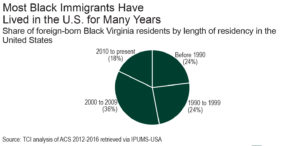

Many of Virginia’s Black immigrants have been living in the United States for a long time. One in four Black immigrants in Virginia have lived in the United States since at least the 1980s, and another one in four have resided here for since at least the 1990s. This means that half of Black Virginian immigrants have been living in the United States for two decades or more, providing the opportunity to put down roots and adapt their job skills to the needs of their communities. Immigrants from Jamaica and other Caribbean countries are particularly likely to have been in the United States for many years, with 46 percent of Black Virginians born in the Caribbean living in the United States since at least the 1980s.

The relatively long periods of time that many Black immigrant Virginians have been living in the United States means many have sufficient years of residency to become naturalized citizens, a process that usually requires many years of residence and passing a test on U.S. history, culture, and government. Almost six in ten foreign-born Black Virginians are naturalized U.S. citizens. Unsurprisingly, citizenship rates are highest for communities with the longest lengths of tenure in the United States, with two-thirds of Caribbean-born Black Virginians holding citizenship status. However, even among Black immigrants from Ghana, a community with many newer residents of the United States, more than half are naturalized U.S. citizens. Specific status information is not available in Census data for non-citizen immigrants, but it is likely that these Virginians hold a range of statuses, including lawful permanent residency, temporary visas, refugee and asylum status, temporary protected status, student visas, and individuals without authorization to remain in the country. Many Virginia families include individuals with a variety of immigration statuses, so public policies meant to target individuals with particular statuses can also harm their lawfully present family members, including U.S. citizens.

Economic Contributors

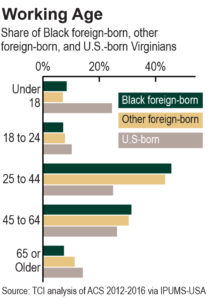

In addition to being committed members of Virginia communities, foreign-born Black Virginians make significant contributions to the state’s economy. Nearly three-quarters of all Black immigrant Virginians over the age of 16 are currently employed, a share that is somewhat higher than that of other immigrant Virginians and 13 percentage points higher than that of non-immigrant Virginians. (Among non-immigrant Virginians, Black adults have relatively high unemployment rates and therefore are less likely than their non-Black non-immigrant peers to be currently employed. This is not because they are not interested in working, but because they are actively seeking jobs and cannot obtain them.)

Most Black immigrants living in Virginia are of prime working age, which helps contribute to their high rates of employment. Over three-quarters of foreign-born Black residents of Virginia are between the ages of 25 and 64, even more than the 74 percent of other foreign-born residents of Virginia and significantly more than the 51 percent of non-immigrant Virginians.

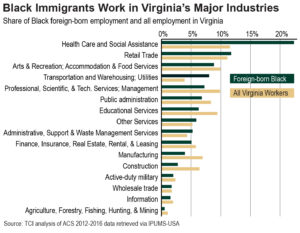

Black immigrants work in every major Virginia industry but are particularly important for Virginia’s health care and social services sector. More than one in five Black immigrant workers in Virginia is employed in this critical sector, compared to about one in nine U.S.-born Virginians. Ghanaian- and other west African-born Black Virginians are particularly likely to work in the health care and social services sectors. Black immigrants are also more likely than other Virginians to work in the transportation and warehousing sector, while being less likely than other Virginians to work in construction or the educational sector.

In addition to working in all of Virginia’s major industries, Black immigrants are also important members of Virginia’s small business community. Over 2,300 self-employed Black immigrant Virginians own incorporated businesses. That is just over 1 in every 50 Black immigrants — slightly higher than the rate for U.S.-born Virginians but lower than that of non-Black immigrants.

Big Obstacles: Income, Language, Housing Affordability, and Health Insurance

Despite the important economic contributions made by Black immigrants to Virginia, these individuals and their families face significant economic barriers.

Foreign-born Black Virginians typically have high levels of educational attainment, yet many are paid less than other Virginians with similar levels of education. More than one-third of foreign-born Black adults over the age of 24 has a bachelor’s degree or higher, while just 12 percent have less than a high school education. These rates are very similar to those of U.S.-born Virginians and appear relatively similar across Virginia’s major Black immigrant communities. But college-educated Black immigrant Virginians have lower individual incomes than other college-educated Virginians. If we look at adults in their prime working years (age 25-64) who have a bachelor’s degree but no graduate degree, just 10 percent of Black immigrant Virginians have personal incomes above $100,000 compared to 13 percent of U.S.-born Black Virginians, 18 percent of non-Black immigrant Virginians, and 23 percent of U.S.-born non-Black Virginians. And 60 percent of Black immigrants with bachelor’s degrees have personal incomes under $50,000 compared to just 45 percent of U.S.-born non-Black Virginians.

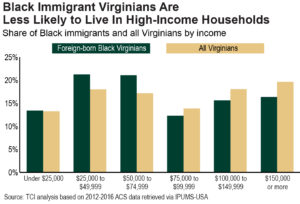

As a result of lower individual incomes despite high educational attainment levels, foreign-born Black Virginians tend to live in households with lower incomes than other Virginia households. This fact is particularly striking given that most Black immigrants in Virginia reside in the high-cost Northern Virginia area. Just 32 percent of Black immigrants live in households with incomes above $100,000, compared to 37 percent of all U.S.-born Virginians and 61 percent of U.S.-born Virginians living in Northern Virginia. Immigrants who were born in Jamaica or elsewhere in the Caribbean are somewhat more likely than other Black immigrants to have high household incomes (over $100,000), and immigrants from Ethiopia and elsewhere in east Africa appear to most frequently have relatively low household incomes (under $50,000 a year). At the lower end of the income spectrum, one in eight Black immigrants lives in a family whose income is below the poverty line, slightly higher than the share of other Virginia immigrants or U.S.-born Virginians — although significantly lower than the rate for U.S.-born Black Virginians.

Several factors likely contribute to Black immigrant Virginians’ lower returns on education. Language is a factor for some though far from all Black immigrants, as is trouble getting overseas professional credentials recognized and possibly more limited social and business networks. However, it is hard to discount the role racial discrimination plays in the American labor market. The existence of discrimination against African-Americans is well-documented, and it is likely that this discrimination also extends to Black immigrants. For example, research using matched-pair tests shows employers strongly favor non-Hispanic white applicants over Black applicants, and actually favor white applicants who had recently been released from prison over Black applicants who were not incarcerated. Black and Latino applicants were also more likely to be channeled to jobs that had less customer interaction and more manual labor. Other research shows that Black workers are paid less than non-Hispanic white workers even within the same private-sector occupations and that these differences remain even after controlling for education, experience, region, and marital status.

Most Black immigrants in Virginia have high levels of English fluency, but language access is still a significant barrier to full participation for some in this population. Three-fourths of Black immigrants in Virginia report speaking only English or speaking English “very well,” and another 17 percent report speaking English “well.” However, for the one in four Black immigrants in Virginia who do not speak English at least very well, about 27,000 Virginians, language access is a significant barrier. To the extent that non-English materials and interpreters are widely available in Virginia, these services are most readily available in Spanish, and many Black immigrants were born in non-Spanish speaking countries. About one-third of the 27,000 Black immigrants who are less than proficient in English were born in Ethiopia, where Amharic and Oromo are the most common languages, but over 100 languages are spoken.

One way to make it more likely that everyone can find a job that matches their skills and abilities would be to make sure immigrant workers who do not speak English “very well” have access to language training or language sensitive work programs. Virginia should structure workforce development and adult education programs in ways that make them more accessible to workers with less proficiency in English. Virginia can also use tools like interpretation lines to make sure everyone, including those who speak less common languages, can navigate community and public services.

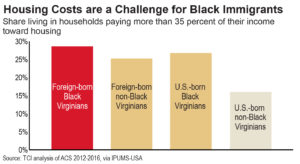

Low incomes present particular challenges for Black immigrant workers and families in Virginia because so many live in the high-cost Northern Virginia area, where rent, child care, and other living costs far outpace national averages. As a result, almost three in ten Black immigrants live in a household that pays more than 35 percent of their income toward housing costs, which means they’re paying a higher share of their income toward housing than most experts consider affordable. By comparison, just 19 percent of all Virginians and 25 percent of non-Black immigrants live in households that pay that high a share. Together, relatively low incomes, high housing costs, and being less likely to have inherited a property in Virginia may explain why only four in 10 foreign-born Black Virginians live in owner-occupied homes, compared to two thirds of all Virginians.

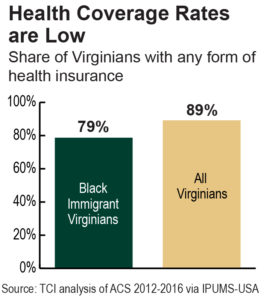

Another significant challenge is that, despite high employment levels, one in five foreign-born Black Virginians have no form of health insurance, lower than the one in four rate for other immigrants but much higher than the one in ten U.S.-born Virginians who have no health insurance. This problem is particularly acute among African-born Black immigrants in Virginia. More than one in four Ethiopian- or Ghanaian-born Black Virginians lacks health insurance, with similarly high rates among Black immigrants who were born elsewhere in Africa. Meanwhile, about one in seven Black immigrants who was born in Jamaica or elsewhere in the Caribbean has no health insurance.

Black immigrants experience very low levels of health coverage in part because Virginia imposes higher limits than the federal government on access to public coverage for legal immigrants. Although this data was gathered during the implementation of the major coverage expansions of the Affordable Care Act and, therefore, does not capture the full benefits of those coverage expansions, the magnitude of uninsured non-citizens likely remains unchanged as of 2018. Effectively implementing Virginia’s Medicaid expansion should expand access to health insurance for foreign-born Black Virginians who are naturalized U.S. citizens. However, unauthorized immigrants are ineligible for essentially all of the coverage expansions, and even lawfully present non-citizens face significant barriers to coverage. As a result, many non-citizens are likely still to be uninsured.

While obstacles exist, Black immigrants living in Virginia are critical to the economic health and vitality of the state. But the challenges they face hinder their economic success and abilities to contribute to their communities. Lawmakers at the state and local levels — in partnership with Virginia’s diverse Black immigrant communities–should consider the ways in which we can use public policy to make sure all of Virginia’s Black immigrants have the opportunity to succeed and fully contribute to building the types of thriving communities we all want to live in. This discussion should include policies that dismantle barriers by supporting language assistance and civic engagement, more effective nondiscrimination and racial justice initiatives, and improving access to health coverage and affordable housing. Expanding opportunity for new Virginians, including Virginia’s diverse Black immigrant communities, is the right thing to do not just for these workers and families, but for all of our communities.

The Commonwealth Institute thanks Amaha Kassa of African Communities Together, Mohamed Gula of EmgageUSA, and Jonathan Jayes-Green of the UndocuBlack Network for their invaluable assistance and advice as we began this project.

Related Analysis:

Virginia Immigrants in the Economy (April 2017)

A Closer Look: The Contributions of Hispanic and Latino Immigrants to Virginia’s Economy (pdf; released June 2015)

A Closer Look: The Contributions of Asian and Pacific Islander Immigrants to Virginia’s Economy (pdf; released June 2015)