September 1, 2022

State of Working Virginia

This is a joint report with Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy (VICPP).

Introduction

No matter what we do for a living, who we are, or what language we speak, we all work hard for our families and look to a better future. Although many leaders tout a strong economy and boast of Virginia as a top place for business, these accolades often ignore the experience and well-being of working people. Our economy is doing well only when people are doing well and have the resources to thrive as well as survive. Yet the data on how working people are doing today suggests that many still face barriers to economic security. Policymakers need to do more to support workers who earn low wages and who face barriers to policies and programs that support working families. Together, we can develop and improve systems that allow everyone — no matter what we look like or where we are from — the opportunity to thrive and to share in the prosperity that working people help to create.

Over the last five years, there have been some important policy strides centering issues of concern for workers, especially those being paid low wages. The minimum wage has been raised. Medicaid expansion helped workers employed in low-wage jobs without health care benefits to access affordable and comprehensive care. Wage theft protections have been strengthened. Virginia has invested heavily in job training opportunities and has raised wages for its own state employees. In June 2022, we improved Virginia’s Earned Income Tax Credit, which will provide an income boost to families with low incomes at tax time. These are important steps for working people, their families, and Virginia.

But more could and should be done to honor, support and strengthen working people in Virginia. Although many workers in high-paying jobs are doing quite well, too many others are being pushed further behind and unable to cover the basic costs of living. Inflation is exacerbating problems — particularly for people with low incomes who must spend a large share of their incomes on items subject to high inflation, such as food, gas, and rent — and wages have not kept pace.

The State of Working Virginia focuses on facts – what does the data tell us about how all workers in Virginia are faring. And we offer this report as a tool to center the conversations around business and our economy on the well-being of the very people who drive it — workers. Working people are the foundation of thriving communities, thriving business, and a thriving economy. Workers and how they are treated matter for Virginia. We hope the information in this report will be helpful as we strive to build a more just and welcoming Virginia.

Key Takeaways

- Over the last five years, there have been some important policy strides centering issues of concern for workers, especially those paid low wages.

- Yet the most recent data shows many workers are still facing barriers to economic stability, particularly for Black and Latinx Virginians who have faced long-standing racial discrimination in education, hiring, and wages. The wage gap for Virginia’s Black workers has barely shrunk since 1979. Black workers in Virginia were paid 72 cents for every dollar a white worker was paid in 1979 and 74 cents for every dollar a white worker made in 2021. The wage gap between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white workers has actually widened from 72 cents for every dollar in 2001 (the earliest data available) to 68 cents for every dollar in 2021.

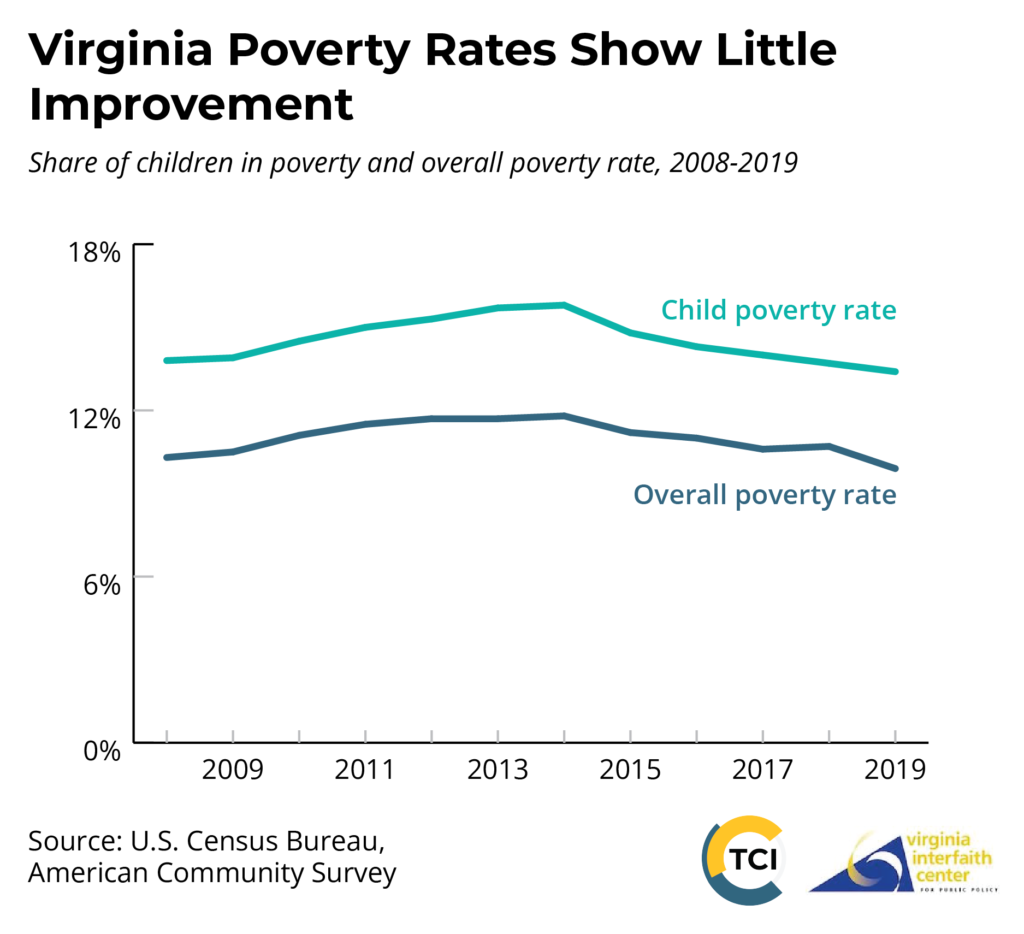

- While Virginia overall is often a top 10 state when it comes to median household income, available data shows that 9.9% of people overall and 13.4% of children in Virginia were in poverty in 2019.

- There is a lack of comprehensive and widespread supports for workers in Virginia — such as paid sick days or paid time off, affordable child care, and adequate employment benefits. Without careful planning and implementation, many may lose health care or fall victim to wage theft.

- Virginia has a strong history of labor organizing, and, as a result of these historical efforts, union workers in Virginia have consistently made more than their non-union counterparts. However, major challenges that limit workers’ right to organize in Virginia still exist and must be addressed.

- Together, we can develop and improve systems that allow everyone — no matter what we look like or where we are from — the opportunity to thrive and to share in the prosperity that working people help to create.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Bobo, Executive Director of Virginia Interfaith Center, for co-authoring this report and Emily Griffey, Chief Policy Officer of Voices for Virginia’s Children, for her helpful suggestions and technical assistance related to child care.

Working People in Virginia and Their Wages

Overview

No one should have to worry about whether they will bring home enough to feed their family and keep a roof overhead, and everyone in Virginia should get a fair return on their work. Virginia has made some important progress on income and wages for working families, particularly those who are paid minimum wage and people with incomes below the poverty line. However, the overall outlook on income and wage gains and disparities is bleak – especially for working people of color.

Income and Poverty Data

The median household income in Virginia in 2019 was $76,456, which counts everyone in the house and reflects the many single person households with lower-income young or older people. The median income for a four-person family was $93,497.1 Both of these are increases (5%) from the previous year. However, although more recent reliable income data is not available due to data collection problems during the pandemic, households’ and families’ buying power has likely eroded recently because inflation outpaced gains. In addition, there are significant differences in median household and family income between different parts of the state, with northern Virginia’s figures significantly higher than the rest of the state, especially south and southwest rural areas.2

While Virginia overall is often a top 10 state when it comes to median household income, not everyone is seeing these benefits and many are still living at or below the poverty line.

Some progress has been made on the economic well-being of adults and children in the state who live in poverty, though data limitations do not currently allow us to understand the full scope of the progress. Available data shows that Virginia’s overall poverty rate and childhood poverty rate in 2019 decreased from the year prior to 9.9% and 13.4%, respectively. This demonstrates little improvement over the course of the previous decade.

Thankfully, many working families with low incomes will now see an income boost at tax time. In a major recent win, Virginia lawmakers made the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) partially refundable starting in 2023 for tax year 2022, which will likely equate to a few hundred dollars in additional refunds per qualifying family. Around 600,000 working families with children in Virginia receive the federal EITC, and many of these families will benefit from the state’s improved credit. Collectively, these families will see an additional $160 million that they had been missing out on every year.3 This change also helps to address Virginia’s upside-down tax code. Historically, working families with low incomes in Virginia have paid more in state and local taxes as a share of their income than high-income Virginians. Future data on overall poverty and childhood poverty will be able to illustrate the full impact of a partially refundable EITC.

Median Wages

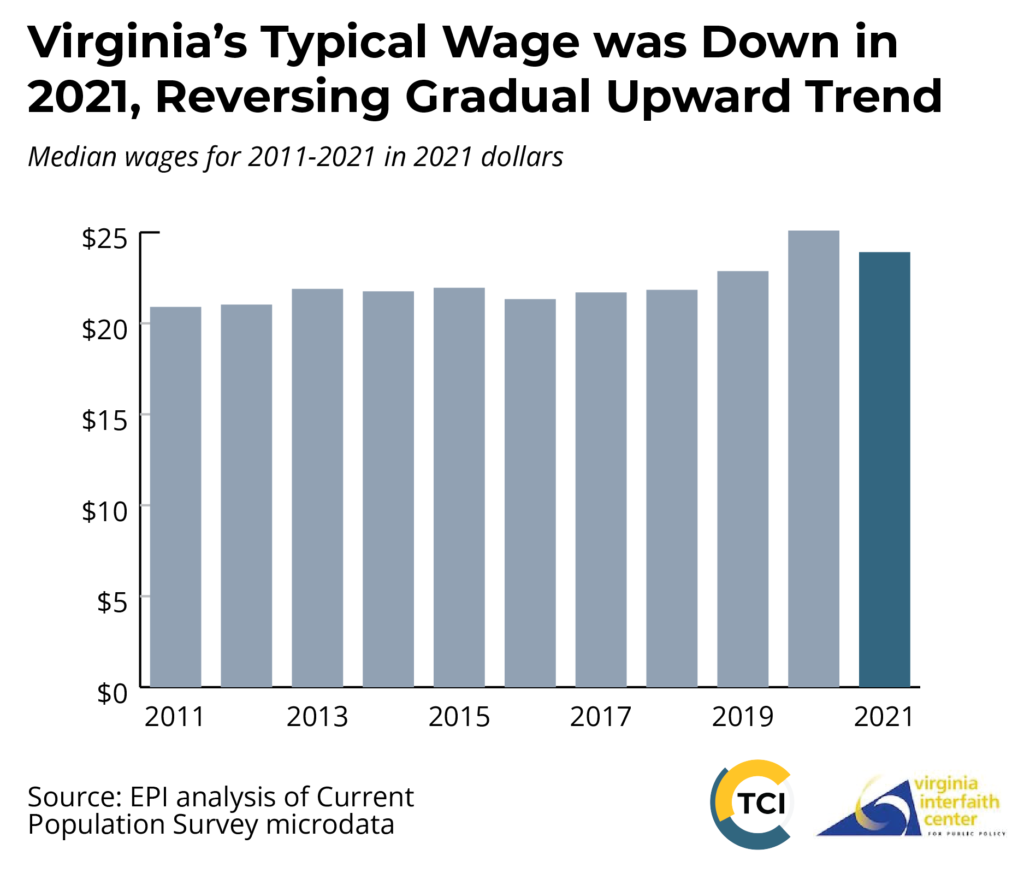

Virginia’s median wage in 2021 was $23.91, down compared to the prior year after adjusting for inflation.4 This reverses the gradual upward trend experienced for several years prior.

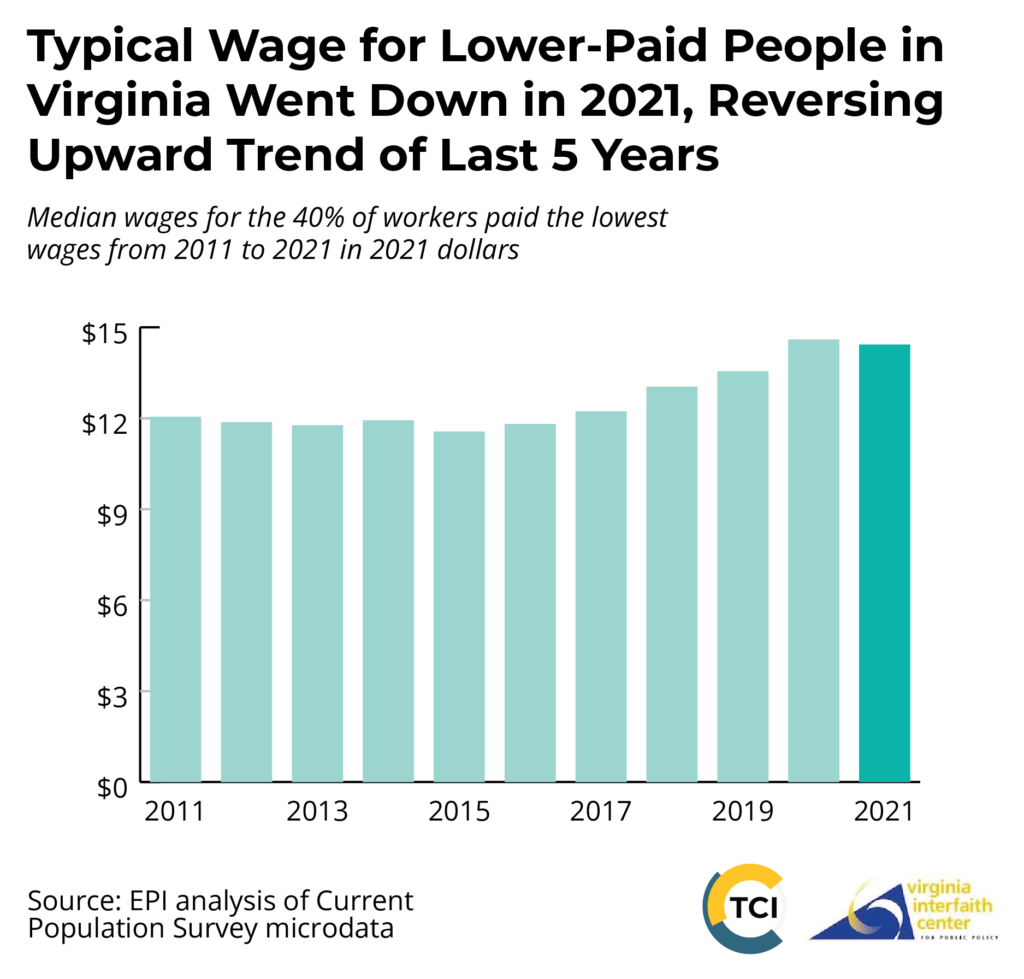

After adjusting for inflation, the median wage for lower-paid Virginians — the 40% of workers paid the lowest wages — also went down from $14.60 to $14.46 between 2020 and 2021, reversing the upward trend of the last 5 years.5 This data may reflect the impact of the 2020 pandemic,6 including lower-wage workers who were more likely to be put out of work during 2020 and therefore not be included in the calculation of median wages for low-wage workers.7

The significant cost increases in 2021 and 2022 for gas, groceries, rent, and other essentials mean that working Virginians will need significant increases in their wages and incomes just to keep up, let alone get ahead. When 2022 state-level wage and income data is released, it will be important to understand it in the context of the significant inflation that has been occurring.

A further breakdown of Virginia wage data has alarming implications for racial equity. Black Virginians and, more recently, Latinx Virginians have historically faced systemic barriers to advancement — including long-standing racial discrimination in education, hiring, and wages — and have been stuck in low-wage occupations with little ability to gain better pay. Black workers in Virginia were paid 72 cents for every dollar a white worker was paid in 1979 and 74 cents to every dollar a white worker made in 2021. While the wage gap for Virginia’s Black workers has barely shrunk, the wage gap between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white workers has actually widened from 72 cents for every dollar in 2001 (the earliest data available) to 68 cents for every dollar in 2021.8

The wage gap for women compared to men illustrates a more positive picture, but not an equitable one: from 1979 to 2021, women went from being paid 64 cents to 84 cents for every dollar made by men. Women of color – who are at the intersection of racism and sexism – are hit the hardest by wage inequality in Virginia, with Black women being paid just 59 cents for every dollar paid to white men and Latina women being paid just 52 cents.

The ability to join together in a union and put power in workers’ hands also has clear implications for wages. Union workers have made more than non-union workers in Virginia since at least 1979. In 2021, working people in a union were paid 20% more on average.9 More people being in unions would also benefit non-union workers, since when a high share of workers are in a union, they help raise the bar and increase wages for everyone in their industry.10

Minimum Wage vs. Living Wage

As the result of many years of organizing by advocates and working people in Virginia, lawmakers passed historic legislation in 2020, increasing Virginia’s minimum wage from $7.25 and charting a path to achieve $15 an hour by 2026.

People who are paid minimum wage saw an increase to $9.50 an hour in 2021 and $11.00 in 2022. But the minimum wage will be frozen at $12.00 an hour as of January 2023, unless the General Assembly agrees to let it continue on the path to $15.00 an hour.11 The law also tasks several state agencies with evaluating the feasibility of having a regional minimum wage, with a focus on employee benefits, income inequality, and farmworkers (who are currently excluded from the state minimum wage). By locking in existing lower pay in areas with many Black workers and by reducing the overall number of people who benefit from raising the wage, a lower minimum wage in some areas of the state could further cement wage inequality in Virginia, particularly for Black workers and women.

It is important to recognize that a significant cause of widening income disparity is because the federal minimum wage, which Virginia had previously tied its minimum wage to, has not increased relative to worker productivity. For the first 30 years after the minimum wage was created in 1938, the minimum wage rose as worker productivity increased, meaning that all workers shared in the nation’s prosperity. But for the last 55 years, the federal minimum wage has not increased as productivity increased. If it had, the minimum wage would have been $21.45 in 2020.12

Localized living wages in Harrisonburg, Charlottesville, Richmond, and Northern Virginia currently range from $15 to $17.50 per hour, according to The Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy’s Living Wage Certification program, but even these figures are too low given escalating costs for almost every expense category for workers and their families. The Virginia Living Wage Certification program is exploring partnering with Living Wage for Us (www.livingwageforus.org), a national organization that offers a sophisticated calculation for commuting regions that would better reflect real costs in Virginia.

Regardless of which calculation is used, it is clear that wages for workers in low-wage jobs are not earning enough to survive.

Advocacy and Organizing

- Continue the minimum wage increases for Virginia’s workers. By July 1, 2024, the General Assembly should enact the planned increases to $13.50 beginning January 1, 2025, and $15.00 beginning January 1, 2026, and maintain the automatic wage increases pegged to inflation.

- Encourage businesses to become living-wage certified and encourage people to patron living-wage businesses.

- Increase collective bargaining and unionization across Virginia. Union workers in Virginia have consistently made more than their non-union counterparts. And research shows that increased local unionization lifts wages for working people whether or not they are union members themselves. National data also indicates that collective bargaining particularly benefits Black and Latino workers.13 See Workers Rights to Organize in Virginia for more information about collective bargaining and unions in the commonwealth.

- Pass a strong Virginia Equal Pay Act to strengthen protections against gender-based pay discrimination in the workplace. Current Virginia code exempts employers covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and does not have any civil penalties attached to it.

- Push state and local leaders to lead the way with fairness actions on equal pay, including, but not limited to, laws that require employers to post salary ranges for job openings, limitations on employer reliance on salary history (which was already done in Virginia’s state agencies on July 1, 2019),14 and mandated employer reporting of pay data.15

Benefits and Supports for Working People in Virginia

Overview

Working people need to know that their economic security will not be threatened if they get sick, have a child, or need to care for a loved one. Current access to comprehensive paid leave and benefits in the commonwealth leaves much to be desired. Virginia must do more to expand paid sick days, paid leave, health care, and child care access and affordability.

Paid Sick Days

Every worker gets sick or will need to care for a family member at some point. Virginia has approximately 1.2 million workers without any paid sick days16 or even any paid time off (PTO) that can be used when a worker or the worker’s child is sick.

Most rich countries have a paid sick day standard.17 Currently, 127 countries provide at least one week of paid sick days.18 The United States has no paid sick day standard, which is why states, cities, and counties have increasingly been passing paid sick day standards to guarantee that all workers have a minimum number of paid sick days.

Paid sick time is important for all working people, but especially for workers in low-wage jobs. A low-wage worker who is paid $12 an hour who loses 3.5 days of wages ends up losing the month’s grocery budget.19 Given how close to the edge almost half of Virginia’s families live, not having paid sick days creates serious challenges for working people and their families. Consequently, studies show that workers without paid sick days go to work sick in order to avoid losing their income,20 potentially infecting their coworkers and customers. Workers without paid sick days are also more than twice as likely to send their children to school sick.21

Many of Virginia’s essential workers do not have paid sick days. For example, two-thirds of Virginia’s grocery store chain workers22 and 85% of chain pharmacy workers do not have paid sick days.23

In 2021, the Virginia General Assembly passed a bill to provide paid sick days to 30,000 home care workers.24 This was an important step forward, and this standard should be extended to all Virginia workers.

Paid Leave

Paid parental leave is associated with improved health, development, economic, and social outcomes for families.2526 Job-protected medical leave ensures that workers do not have to worry about losing their employment or wages while they or a loved one experience an illness or injury that keeps them out of work for an extended period. And access to paid family leave has a positive effect on job searching and employment for women around the time of childbirth and reduces a mother’s risk of poverty after childbirth.27 Despite these critical benefits, Virginia’s working families currently have remarkably low access to paid family leave.

About 3 million working people in Virginia — 79% of civilian non-federal workers — do not have paid family leave through their employer.28 Furthermore, unpaid leave under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) is inaccessible for 55% of Virginians.29 Due to historic and present-day barriers to wealth and economic mobility, Black and Latinx families tend to experience higher rates of poverty and lower pay, making unpaid leave even more impractical and inaccessible. In Virginia, 67% and 57% of Latinx and Black workers, respectively, are either ineligible or cannot afford to take unpaid leave through the protections provided by the FMLA leave.30

Virginia residents working for the federal government did gain access to 12 weeks of paid family leave in October 2020.31 Due to effective worker organizing and advocacy campaigns, Fairfax County provides six weeks of a comprehensive paid family leave program.32 But these are not statewide programs. While comprehensive statewide paid family leave legislation was introduced in the 2022 legislative session, the bill did not pass into law. The lack of statewide paid leave has devastating costs for Virginians of all backgrounds, their families, public health, and the economy.33 Lawmakers should continue to pursue statewide 12-week paid family and medical leave to build a stronger economy, healthier families and businesses, and greater equality for all women and families.

Health Care

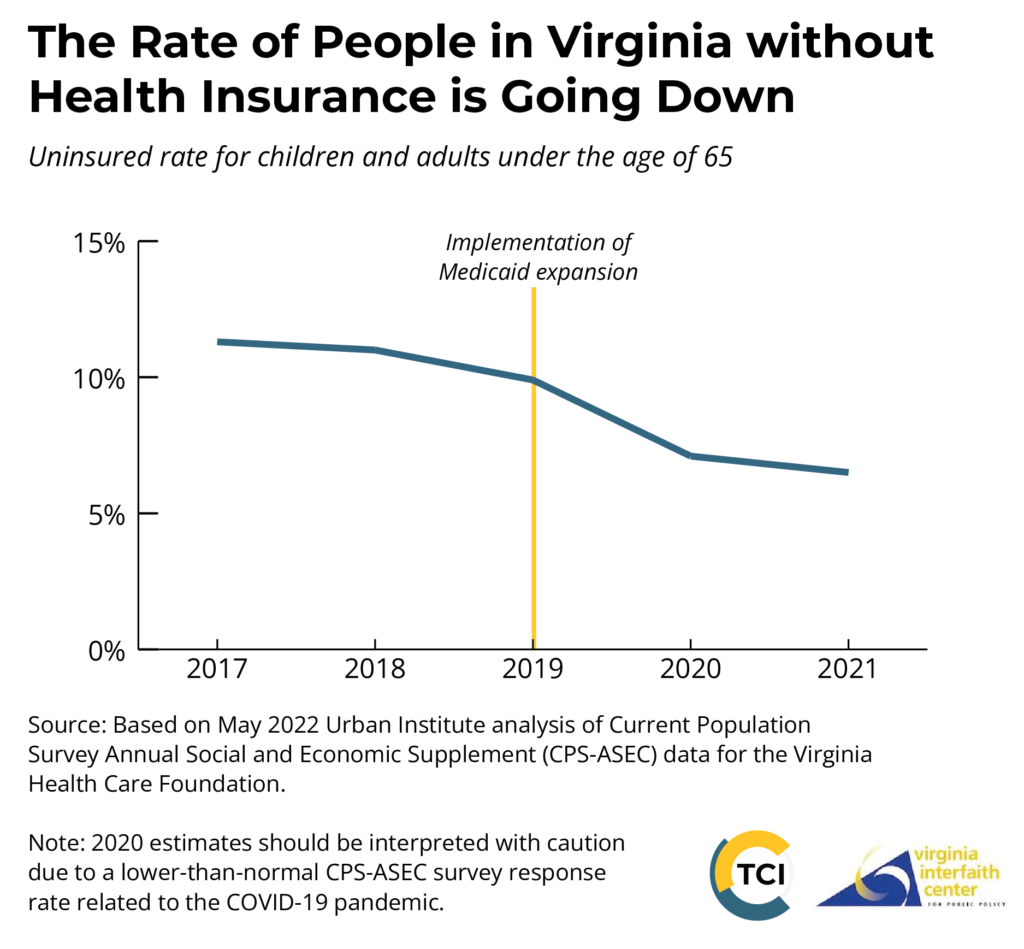

In 2018, after many years of advocacy and public support, Virginia lawmakers provided greater access to health care for adults earning up to 138% of the federal poverty limit by expanding Medicaid.34 This decision and subsequent successful implementation of Medicaid expansion has given workers with low incomes throughout Virginia another health coverage option. This is important for many low-wage workers who often do not have access to health coverage through their source of employment or are offered health coverage that costs a large share of their income.

Medicaid has always been critical to working families in the commonwealth, and now that it provides health care coverage to 1 in every 5 Virginians it is more important than ever before.35 As of August 2022, more than 675,000 adults under the age of 65 have enrolled in Medicaid coverage.36 And the uninsured rate for adults under 65 has dropped from 12.7% in 2018 to 8.2% in 2021, according to Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC) data.37 This suggests that many individuals were previously without health insurance before becoming eligible for Medicaid.

Virginia workers have also benefited from changes at the federal level. As part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021, individuals purchasing health coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) individual marketplace have received additional financial assistance through enhanced advanced premium tax subsidies, which have lowered out-of-pocket premium costs for coverage. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, nearly 308,000 Virginians signed up for marketplace coverage for 2022 — an increase of more than 17% over 2021 that was due in large measure to the premium subsidy expansion.38 These subsidies were recently extended through 2025, meaning continued access to affordable coverage for hundreds of thousands of people in Virginia.39 Additionally, current federal rules put in place during the pandemic protect people who receive health insurance through Medicaid from losing that coverage.

However, without appropriate planning and action for future events, some of the progress we have enjoyed in recent years could be undone.

Resuming Medicaid Eligibility Redeterminations

Millions of people could lose health coverage nationally when the federal COVID-19 public health emergency ends and states resume their regular eligibility review of everyone who Medicaid currently covers. A provision in the 2020 federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act allowed states to receive more federal funding for Medicaid if they agreed to deem current and newly enrolled individuals eligible for Medicaid until the end of the month in which the public health emergency ends.40 Once that occurs, the state and local agencies will need to redetermine if people enrolled in Medicaid are still eligible.

Making sure that people enrolled in Medicaid coverage have updated their contact information and are aware of eligibility redeterminations that will likely occur in the coming months will be critical to ensuring eligible people remain on Medicaid. State agencies should work closely with stakeholders — including people who are impacted and their advocates — during the planning and redetermination periods to identify any issues before disenrolling individuals. For people who are no longer eligible for Medicaid, connecting them to other forms of comprehensive coverage such as through an employer or the ACA marketplace will be vital to making sure that uninsured rates for working adults do not spike in the state.

Improving Racial Equity in Health Coverage

Virginia has taken several positive steps to break down barriers to health coverage, including covering people enrolled in Medicaid for a year after childbirth. This choice is expected to improve maternal health outcomes, particularly for Black mothers who face a myriad of systemic issues, including racism and sexism, that impact their health.41 As part of the initiative, coverage has also been expanded to include doulas — who play a vital supporting role during pregnancy. However, there are continued barriers to health coverage for people with low incomes as well as non-citizen adults under the age of 65 who are uninsured at a rate over 5 times higher than their citizen counterparts (26.6% compared to 5%).42 Workers with undocumented status are barred from enrolling in comprehensive health coverage through Medicaid or the ACA marketplace unless they are pregnant. Undocumented workers may be eligible for Emergency Medicaid; however, that only covers life-threatening and serious emergencies. Recent efforts to expand health coverage to all workers regardless of immigration status, such as what occurred in California, should be explored to make sure all working people in Virginia have the opportunity to access comprehensive and affordable coverage.43

Child Care

Child care is incredibly expensive for nearly all working Virginians, and families with infants or multiple young children bear an even greater financial burden. Virginia is ranked 10 out of 50 states and the District of Columbia for most expensive infant care. The average annual cost of child care in Virginia is $906 for 4-year-olds and $1,172 per month for infants, equal to $10,867 to $14,063 per year. Currently, a minimum-wage worker with an infant in Virginia would need to work full time for 32 weeks just to pay for one infant’s child care.44 Working families need affordable child care assistance.

Despite these costs, Virginia’s child care workers (also known as early educators) themselves struggle to get by: With a median income of $22,210, a child care worker in Virginia would have to spend over three-fifths of their earnings on infant care for their own child.45 Because of low pay, child care workers also have a high rate of participation in public assistance benefits.46 It is critical that child care workers receive better compensation to remain in the field and provide a stable source of care for families.

Virginia’s child care practices are changing to address the financial burden on families and child care workers. Through Virginia’s expanded Child Care Subsidy Program, families can apply for financial help if their income is below 85% of the state median income ($74,712 for a family of three)47 and meet other criteria. The state pays a portion of the child care costs directly to the provider, though the maximum rate varies for different regions of the state.48 Virginia expanded eligibility for the subsidy program through June 30, 2024,49 allowing more families to access financial assistance.

As a result of these improvements, Virginia is one of eight states that reduced the number of children and families on waiting lists for child care assistance in 2021 (out of 13 states that had a waiting list or frozen intake),50 and was one of 23 states that increased at least some of their base or tiered payment rates for child care providers from 2020 to 2021.51 Most importantly, Virginia also plans to adopt voluntary wage scales to help make sure child care workers see the benefit of increased state reimbursement rates, implement new reduced parent co-payments (the amount parents pay to supplement the state payments) in January 2023, and increase payments to address the true cost of care.52

Advocacy and Organizing

- Ensure that people enrolled in Medicaid coverage have updated their contact information and are aware of eligibility redeterminations that will likely occur in 2023.

- Connect those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid to other forms of comprehensive coverage such as through an employer or the Affordable Care Act Marketplace, which will be vital to making sure that uninsured rates for working adults do not spike in the state.

- Create a requirement for employers to offer at least five paid sick days to all employees.

- Support a 12-week paid family and medical leave program that provides wage-replacement payments to workers who need to take periods of time off longer than ordinary sick days would cover. A 2020 study found that 84% of registered voters in Virginia support a 12-week paid family and medical leave policy accessible to all working people.

- Recognize that affordable, accessible child care relies on attracting and retaining high-quality early childhood educators by establishing fair wages for the field and providing necessary public funds so that additional costs do not fall on parents.

- Maintain and continue to build on recent improvements in income eligibility, parent co-pay obligations and provider reimbursement to provide maximum benefit to families and increase compensation for child care providers. These initiatives have been supported using COVID response funds (ARPA) that will end in the coming years.

- Join other parents and providers in advocating for more affordable child care by joining the Virginia Promise Partnership. https://www.vapromisepartnership.com/

- Continue the expanded support offered through the Child Care Subsidy Program.

Wage Theft and Worker Protections for Virginians

Overview

Wage theft is when employers break the law and do not provide workers all their legally owed wages. This happens in a variety of ways. Examples of wage theft include not paying the minimum wage, not paying overtime wages when eligible workers work more than 40 hours per week, not paying workers for all the hours worked, refusing to provide workers’ last paychecks, taking illegal deductions from workers’ paychecks, or calling workers independent contractors when they are really employers, thereby cheating them of employer-provided taxes and protections.

Wage theft is common practice in many sectors of the economy, such as restaurants, retail establishments, construction, landscaping, nursing homes, child care centers, and many others.53 Most of the sectors are ones that pay low wages. Consequently, many low-wage workers who are already struggling to make ends meet are also more likely to have some of their wages stolen.54

Wage theft occurs for several reasons including:

- The laws preventing wage theft are weak.

- Employers do not know the law or intentionally violate the law to enhance their own profits.

- There is little enforcement of wage laws that serve as deterrents against wage theft.

- Workers do not know their rights or are afraid to exercise their rights for fear of firing or retaliation.

- There are not enough unions in Virginia. Unions ensure that wage theft doesn’t happen in their workplaces and help provide legal compliance for the sectors.

Although wage theft can happen to all workers — men and women; young and old; Black, white, and Latinx — it happens the most when workers are vulnerable. Two categories of workers that are particularly vulnerable are immigrants without documentation and people who were formerly incarcerated. Both groups of workers deserve extra support and education. The U.S. Department of Labor has just released a new process that would allow workers without immigration documentation to file employment complaints (acknowledging wage theft) and get support from the Department of Homeland Security. This could give undocumented workers a reprieve from immigration enforcement, and thus encourage them to file complaints about wage theft.55

Wage Laws and Immigrants

The easiest workers to exploit are ones who are already vulnerable. This means the undocumented community in particular is always facing a higher risk of wage theft and exploitation. Carmen* was employed by a small cleaning company. She worked for the company at an agreed-upon rate of $13 per hour, but wasn’t always paid for all her hours. One time, her paycheck bounced and was never refunded. Carmen reached out to Virginia Interfaith Center’s wage theft website (wagetheftva.org) and was connected to an attorney who helped her recover her unpaid wages under Virginia’s new wage theft laws. She recovered more than $2,000 in unpaid wages.

*Name changed to protect privacy

Recent Improvements

In the last four years, Virginia has done a great deal to strengthen its laws designed to protect workers against wage theft. The Virginia General Assembly:

- Removed many of the racist exemptions from the state minimum wage, so more workers were protected. (Virginia continues to exempt farmworkers, which is the last significant racist exemption that needs to be changed.)

- Removed the exclusion of workers paid by the piece from the minimum wage (Virginia was one of only two states that still had this exclusion).

- Established a paystub requirement so workers would know how much they are paid and how many hours they are being paid for.

- Created a private cause of action so private attorneys could represent workers in court and get paid for handling the cases. Given that most labor law enforcement is actually done by the private bar and not government agencies, this law is critical.

- Created a state overtime provision.

- Prohibited employer retaliation for workers filing complaints against wage theft.

- Created a private cause of action for intentional misclassification of workers.

- Enabled collaboration between the Department of Labor and Industries and the Department of Taxation in order to crack down on employers misclassifying workers.

- Prohibited non-compete agreements for workers in low-wage jobs.

Recent Setbacks

In the 2022 legislative session, there were several efforts to roll back worker protections, with one in particular gaining support. The year prior, lawmakers passed a law that strengthened Virginia’s overtime protections, going beyond the minimum set forth in the Fair Labor Standards Act to protect workers’ wages. In 2022, lawmakers dialed back these protections to conform Virginia’s new overtime provision with federal law. As a result, reforms to the state overtime law changed how fluctuating work weeks are handled and overtime coverage for farmworkers and domestic workers was removed.

Enforcement Concerns

Laws are only effective if they are enforced. Virginia’s Department of Labor and Industries (DOLI) is woefully under-resourced and understaffed and thus cannot effectively enforce wage theft laws. All of the enforcement is done based on complaints, which is generally acknowledged as an ineffective way for garnering widespread sector compliance. Effective state labor agencies target sectors that are egregious violators of wage laws, and seek to garner compliance throughout the sector through targeted investigations and enforcement. Although DOLI has gotten modest budget increases, it still has only a handful of staff dedicated to fighting wage theft.

Advocacy and Organizing

- Advocate DOLI budget increases focused on wage and hour enforcement.

- Authorize DOLI to conduct targeted investigations into sectors that routinely steal wages.

- Educate workers about their rights in the workplace.

- Connect workers who have been victims of wage theft with attorneys that can represent them. See www.wagetheftva.org for how to do this.

- Strengthen wage theft laws, including removing the farmworker exemption from minimum wage and restoring the stronger provisions of the Virginia Overtime Act.

- Encourage the formation of workers centers as another structure for supporting workers against wage theft.

Unemployment and the Virginia Employment Commission

Overview

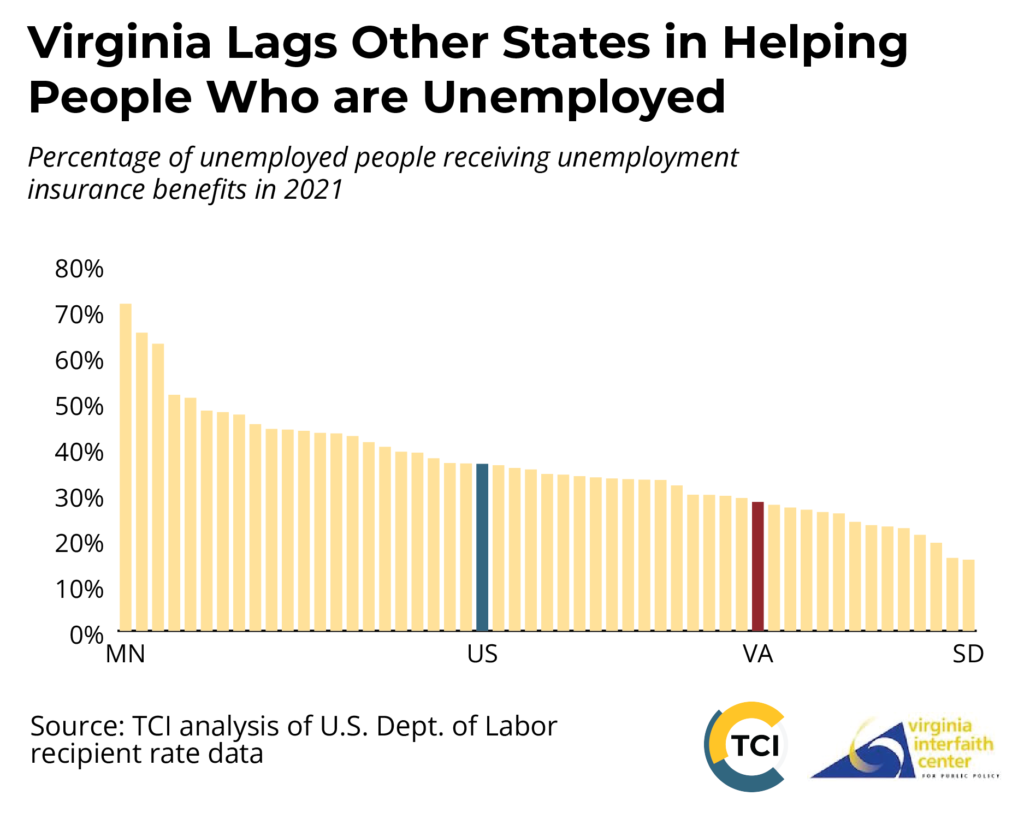

One of the basic promises to U.S. workers and families since the Great Depression of the 1930s is that, when hard times hit and you are laid off, there will be help from the unemployment insurance system. For too many Virginia workers, that promise has proven hollow. The fallout from the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic revealed not only the historic issues with the Virginia Employment Commission, but just how critical a robust unemployment insurance program is to allow workers to keep food on the table and a roof over their heads.

Historic Problems

Unemployment insurance (UI) is a core part of how we make sure that we never have another Great Depression – by ramping up help during economic downturns, the unemployment insurance system is designed to act as an “automatic stabilizer” for communities facing hard times and the economy as a whole.56 Unfortunately, the system has never worked as promised for every worker in Virginia, with many Black workers excluded from the beginning due to a compromise designed to appease racist southern congressmen by excluding agricultural workers and domestic workers,57 and, more recently, low benefits and high barriers to accessing unemployment creating challenges for Virginia families. Every year for at least the last 46 years – the extent of the available data – a smaller share of unemployed Virginia workers receive help from the unemployment insurance system than is typical in the U.S. as a whole.58 In other words, unemployed workers in Virginia are more likely to be left with no help from the unemployment insurance system. And as JLARC noted in a recent report, “Virginia’s standard state UI benefits cover less than half of basic food, housing, and transportation costs for many individuals, particularly those who qualify for lower benefits, live in expensive areas, or have dependents” and both average and maximum benefits in Virginia are below typical levels in other states,59 despite Virginia being a relatively high income and high-cost state.

The significant administrative problems that were revealed during the 2020 recession are a result of a systematically struggling unemployment insurance system in Virginia.60 Beyond the problems of unemployment insurance benefits that are very low compared to the cost of living, the Virginia Employment Commission was unprepared to meet the need for unemployment insurance due to internal problems, including significant barriers to applying for unemployment insurance for people who do not speak and read English, mistakes and delays in benefit approval, and an outdated benefit management system due to long delays in a planned upgrade. This has ongoing consequences, with many Virginians still facing demands for repayment of benefits from 2020 and 2021 even when it was VEC who made a mistake.61

Virginia’s inadequate unemployment insurance program is allowed to exist due to weak federal rules that allow states to keep benefit levels far below what is needed to replace workers’ wages and pay the bills and restrict eligibility, particularly harming Black workers.62 Additionally, insufficient federal administrative funding contributed to the inability of Virginia’s unemployment system to respond to the pandemic. To fix these problems, Virginia and the federal government need improvements not only in administrative processes but also program rules and benefit levels to make the unemployment insurance system fulfill its promise as a stabilizer for individuals, families, communities, and the economy as a whole.

Advocacy and Organizing

- Remove barriers to unemployment eligibility (through a state-only program if necessary).

- Raise unemployment benefit levels to address the problems of too-low benefits identified by JLARC.63 To do so without risking the stability of the trust fund that pays unemployment insurance benefits, Virginia should increase the taxable wage base. Currently, whether a person makes $25,000 or $225,000, only the first $8,00064 of an individual’s annual income is taxed for the unemployment insurance trust fund. Raising the taxable wage base would increase the stability of the trust fund and address the regressivity caused by the current very low threshold.

- Fix language access issues to expand access to Virginians who do not speak English as their primary language.

- Protect workers from mistakes by the Virginia Employment Commission.

- Create systems to ensure that workers’ calls are answered and inquiries are handled promptly.

Workers’ Rights to Organize in Virginia

Overview

The commonwealth has a strong history of labor organizing by working people in Virginia. Workers have organized in the mines of Southwest Virginia, the shipyards in Newport News, Starbucks locations in Leesburg, hospitals in Charlottesville, textile factories in Danville, and more.65 The last several years have seen an acceleration of that trend, with significant gains made for local-level public-sector workers and private-sector workers all over the commonwealth. As a result of these historical efforts, union workers in Virginia have consistently made more than their non-union counterparts.66 By joining together in a union and putting power in workers’ hands, Virginians of all backgrounds are working to ensure that every one of us can care for our families, earn a fair return on our work, have improved benefits, and make our voices heard.

Recent Progress

Since 2020, public-sector workers in Virginia have seen historic gains in both overall organizing efforts and their right to collectively bargain. Virginia’s 2020 repeal of the prior ban on local-level public-sector collective bargaining means local governments are now permitted to bargain collectively with their employees upon the approval of a collective bargaining ordinance or resolution. Since the repeal took effect in May 2021, multiple Virginia localities have seen remarkable organizing efforts by and for public-sector workers to pass strong collective bargaining ordinances.67 Between May 2021 and July 2022,68 Virginia has seen over 15 active local campaigns to ensure collective bargaining for public employees — several of which have already secured victories.

Virginia has also seen overall momentum in union formation at various public and private workplaces across the state in 2021 and 2022, which may reflect national data indicating that a large and growing majority of workers want union representation.69 These successful union efforts include the aforementioned local-level public-sector campaigns, union formation by Starbucks workers in 11 localities across the state, several Virginia-based nonprofits, and workforces at multiple Virginia universities. There are also ongoing organizing campaigns by workers who are already unionized, such as shipbuilders in United Steelworkers (USW) pushing for a better contract at Newport News Shipbuilding, workers at Kroger stores demanding pandemic protections through United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), and workers at Dulles and National Airport seeking paid sick days and employer-provided health care (SEIU 32BJ).

Current Challenges

Major challenges that limit workers’ right to organize in Virginia still exist. Primarily, Virginia is still a “right-to-work” (RTW) state. Often misunderstood in terms of personal freedom by its supporters, right-to-work laws (which allow a person to opt out of paying union dues despite a majority of their coworkers voting to have a union and ratifying a contract) actually make it extremely difficult for workers to unionize at all. As a result, right-to-work diminishes the power and membership of unions over time. The harm from this decline in worker power is most intensely felt by workers who would otherwise be well-situated to make up the middle class.70 The negative impacts of this legislation are especially obvious when comparing right-to-work states with states that do not have such laws: Right-to-work states have lower wages and fewer benefits for individual workers,71 a higher percentage of low-wage jobs as compared to high-wage jobs, and higher levels of workplace discrimination.72 Additionally, Virginia still prohibits public-sector bargaining at the state level. This prohibition was first put in place in 1946 in response to Black hospital workers at the University of Virginia unionizing for better pay and working conditions.

In our glorious fight for civil rights, we must guard against being fooled by false slogans, such as ‘right to work.’ It is a law to rob us of our civil rights and job rights. Its purpose is to destroy labor unions and collective bargaining…

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Advocacy and Organizing

- Support broad and inclusive collective bargaining ordinances at the city or county level and the school board level.

- Grant the right to collective bargaining to all state public-sector workers.

- Repeal such anti-union legislation as right-to-work.

- Increase unionization across all sectors of Virginia’s workforce.

- Engage religious and community leaders in supporting workers who choose to organize so they can organize and engage in collective bargaining without fear of being fired or harassed.

Progress in the Face of Challenges

Although the continued unionization of individual workplaces is essential to advancing worker rights, workers may find significant legal and policy barriers to unionization – especially at the state level. Virginia’s workers must be creative and strategic about organizing their workplaces to form unions. One promising organizing model is that of United Campus Workers at the University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University. Intentionally a wall-to-wall union (meaning that anyone who works for the university can join), UCW members have managed to make gains collectively despite restrictions on state-level public-sector bargaining.

Conclusion

The State of Working Virginia is a complicated one. In the last few years, Virginia has made great strides in improving its laws and worker program supports, such as expanding Medicaid and improving the state’s EITC. But much more needs to be done if workers and their families are truly going to share in the commonwealth’s prosperity.

Virginia’s religious, community, and political leaders need to focus on the concerns of people who are paid lower wages and whose incomes lag greatly behind inflation, who are overwhelmed with childcare costs, who are the ones most likely to not have paid sick days or paid leave, and are most likely to be laid off or victims of wage theft. Additionally, continued worker organizing and increased unionization pose significant opportunities for working people of all backgrounds to better their economic situation at the grassroots level. Virginia’s leaders have long touted that it is a great place for businesses. As other states have demonstrated, we can be great for businesses and the workers who make them successful.

Endnotes

- TCI analysis of 2019 Economic Policy Institute “State of Working X” Income Data. (EPI data is from the Current Population Survey Microdata. 2021 and 2022 income data are not yet available.)

- American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, 2019

- “Governor Northam’s Proposed 2022-2024 Budget,” Virginia Secretary of Finance presentation to the House Appropriations, House Finance, and Senate Finance & Appropriations Committees, Dec 2021; and “Key Features – House Bill 30 As Amended by the Conference Committee,” Va House Approps Committee, May 2022

- TCI analysis of 2019 EPI “State of Working X” Wage Data.

- Ibid.

- Bateman, N. and Ross, M., “The pandemic hurt low-wage workers the most—and so far, the recovery has helped them the least,” Brookings Institute, Jul 2021

- Gould, E. and Kandra, J., “State of Working America: Measuring wages in the pandemic labor market,” EPI, Apr 2022

- TCI analysis of EPI “State of Working X” Wage Data from 1979 to 2021.

- Ibid.

- “Unions help reduce disparities and strengthen our democracy,” EPI, Apr 2021

- (Under existing law, minimum wage will have automatic increases pegged to inflation starting January 2025.)

- Baker, D., “This Is What Minimum Wage Would Be If It Kept Pace with Productivity,” Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), Jan 2020

- Shierholz, H., Poydock, M., Schmitt, J., and McNicholas, C., “Latest data release on unionization is a wake-up call to lawmakers,” EPI, Jan 2022

- Albiges, M., “To reduce pay discrimination, Virginia will stop asking for applicants’ salary history,” Daily Press, Jun 2019

- Bleiweis, R., Frye, J., Khattar, R., “Women of Color and the Wage Gap,” Center for American Progress, Nov 2021

- “Workers’ Access to Paid Sick Days in the States,” National Partnership for Women and Families, May 2015

- Heymann, J., Jin Rho, H., Schmitt, J., and Earle, A., “Contagion Nation: A Comparison of Paid Sick Day Policies in 22 Countries,” CEPR, May 2009

- “Countries with the Best Sick Leave,” IRIS FMP, Jun 2020

- TCI analysis of 2011 EPI “Average monthly expenditures with two working parents each earning $10 an hour.” (EPI data is from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2010. TCI analysis is updated for 2020 consumer expenditures and $12/hour wages.)

- Piper, K., Youk, A., James III, E., and Kumar, S., “Paid sick days and stay-at-home behavior for influenza,” PLOS, Feb 2017; and DeRigne, L., Stoddard-Dare, P., and Quinn, L., “Workers Without Paid Sick Leave Less Likely To Take Time Off For Illness Or Injury Compared To Those With Paid Sick Leave,” Health Affairs, Mar 2016

- “Paid Sick Days Benefit Children’s Health,” National Partnership for Women & Families, Apr 2013

- Schneider, D., and Harknett, K. “Paid Sick Leave in Virginia: Evidence from the Shift Project,” Harvard Shift Project, Dec 2020

- Ibid.

- Schneider, G., “Virginia legislature approves paid sick leave for home health care workers under Medicaid,” Washington Post, Feb 2021

- Burtle, A., and Bezruchka S., “Population Health and Paid Parental Leave: What the United States Can Learn from Two Decades of Research,” Healthcare (Basel), Jun 2016

- “Paternity Leave: Why Parental Leave For Fathers Is So Important For Working Families,” U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL), 2012

- Mejia, F. and Denny, J., “The Time to Care: The Need For a Paid Family and Medical Leave Policy,” TCI, Jul 2019

- “Paid Leave Means a Stronger Virginia,” National Partnership for Women & Families, Feb 2022; and TCI analysis of Census Data from 2011 to 2021; and “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States [Table 33],” USDOL, Mar 2021

- “Working adults who are eligible and can afford FMLA unpaid leave (percent) by race/ethnicity,” diversitydatakids.org, 2022. Workers are considered unable to take unpaid FMLA leave because they are either ineligible based on employer size or job tenure requirements or because 32.3 days of lost wages from unpaid leave, the average length of FMLA leave, would result in their family income dropping to or below 200% of the federal poverty level.

- Joshi, P., Baldiga, M., and Huber, R., “Unequal access to FMLA leave persists,” diversitydatakids.org, Jan 2020

- “Paid Parental Leave for Federal Employees,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Human Resources Management

- Antonio-Vila, L., “Fairfax County passes six weeks of paid family leave,” Fairfax County Times, Jul 2020

- Mejia, F., “Statewide PFML: A Critical Step Toward Racial, Economic, and Health Equity,” TCI, Aug 2020

- Goodnough, A., “After Years of Trying, Virginia Finally Will Expand Medicaid,” The New York Times, May 2018

- Shadowen, H., Pierre-Louis, S., and Barnes, A., “Member Experiences after the First Year of Medicaid Enrollment: Medicaid Expansion Survey,” VCU, Jan 2022

- “Medicaid Expansion Enrollment,” Department of Medical Assistance Services

- Shartzer, A. and Karpman, M., “A Profile of Virginia’s Uninsured in 2021,” Urban Institute, May 2022

- “Marketplace Enrollment, 2014-2022,” Kaiser Family Foundation

- Cox, C., Amin, K., and Ortaliza, J. “Five Things to Know about the Renewal of Extra Affordable Care Act Subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act,” KFF, Aug 2022

- Wagner, J. and Erzouki, F., “Time to Get It Right: State Actions Now Can Preserve Medicaid Coverage When Public Health Emergency Ends,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 2022

- Wikle, S., “Expanding Medicaid Postpartum Care is Critical for Black Maternal Health,” Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), Apr 2021

- Shartzer, A. and Karpman, M., “A Profile of Virginia’s Uninsured in 2021,” Urban Institute, May 2022

- Miranda, M., “California to become first state offering health care to all undocumented residents,” The Sacramento Bee, Jun 2022

- TCI analysis of adjusted childcare costs from the Economic Policy Institute

- “Child care costs in the United States,” EPI, Oct 2020

- Milli, J., “Why Investing in Child Care Providers is Essential for Providers, Children, and Families,” CLASP, May 2022

- “Temporary Changes to Eligibility for the Child Care Subsidy Program: Am I Eligible?” Virginia Department of Education

- “Become a Child Care Subsidy Program Vendor,” VDOE

- “Expanded eligibility for Virginia’s child care subsidy extended through June 2024,” Virginia Tech, Jun 2022

- Schulman, K., “At the Crossroads: State Child Care Assistance Policies 2021,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2022

- Ibid.

- Griffey, E., “Voices Supports Proposed Changes To Child Care Payment Rates And Parent Co-Pays,” Voices for Virginia’s Children, Jul 2022

- “Low Wage, High Violation Industries,” USDOL Wage and Hour Division

- Cooper, D., “Employers steal billions from workers’ paychecks each year,” EPI, May 2017

- “Frequently Asked Questions: Complaints and the Investigation Process,” USDOL Wage and Hour Division

- Rejda, G., “Unemployment Insurance as an Automatic Stabilizer,” The Journal of Risk and Insurance, Jun 1966

- Traub, A. and Diehl, K., “Reforming Unemployment Insurance Is a Racial Justice Imperative,” National Employment Law Project (NELP), Feb 2022

- TCI analysis of USDOL recipient rate data

- “Operations and Performance of the Virginia Employment Commission,” JLARC, Nov 2021

- Ibid.

- Avellino, K., “VEC to begin collecting benefit overpayments July 1, even if it wasn’t your fault,” NBC12, Jun 2022

- “Reforming Unemployment Insurance Is an Economic and Racial Justice Imperative,” NELP, Apr 2022

- “Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws [Table 3-5],” Office of Unemployment Insurance (OUI) Division of Legislation, USDOL, 2021

- “Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws [Table 2-1],” USDOL, 2021

- Mortoo, F., and Borja, M., “History of Labor in Virginia: An Interactive Timeline and Map,” TCI, Aug 2022

- TCI analysis of wage data from EPI from 1979 to 2021

- Borja, M., “How public-sector workers are building power in Virginia,” EPI, Feb 2022

- Sharma, R., “Where can public sector employees collectively bargain in Virginia?” Virginia Mercury, Jul 2022

- Shierholz, H., Poydock, M., Schmitt, J., and McNicholas, C., “Latest data release on unionization is a wake-up call to lawmakers,” EPI, Jan 2022

- Jones, J. and Shierholz, H., “Right-to-work is wrong for Missouri,” EPI, Jul 2018

- Gould, E. and Kimball, W., “‘Right-to-Work’ States Still Have Lower Wages,” Economic Policy Institute, Apr 2015

- “Right to Work,” AFL-CIO