April 23, 2019

New Study Shows Lack of Economic Mobility, Limiting Opportunity for Black, Hispanic, and American Indian Adults

We all want to live in a society where every child has a chance to reach their full potential and every parent can support their family with dignity. Yet, as shown in a new study of economic immobility, entrenched barriers mean too many families – particularly families of color – are left without those opportunities. The good news is that there are public policy tools we can use to take down barriers facing low-income families and communities of color and build a commonwealth with opportunity for all, no exceptions.

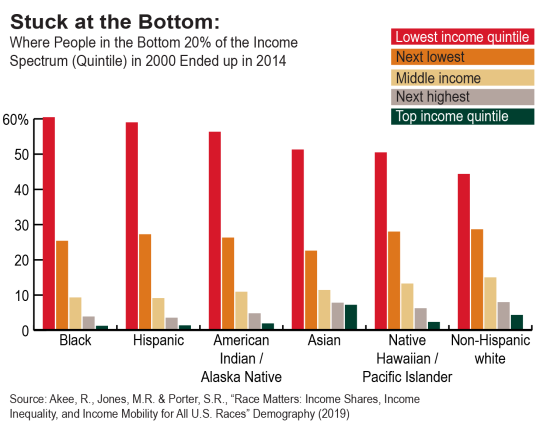

One of the great myths of the United States is the idea that we live in a relatively fluid society where individuals frequently move up (and down) the income scale. However, this is far less true than in the past, and economic mobility may actually be lower in the United States than in many other advanced economies. And a new study of working-age adults shows that Black, Hispanic, and American Indian working-age adults had the highest likelihoods of being stuck at the bottom of the income scale or experiencing downward mobility between 2000 and 2014, while white and Asian American adults who start in the top of the income scale were the most likely to retain that position. Pacific Islander adults generally fall in the middle of these two poles in terms of mobility. (The study adjusted household income to account for household size.)

The new study published in Demography this month “provides detailed evidence for an entrenchment in income across races and ethnicities in the United States for the past two decades. Not only is income disproportionately accruing to the top end of the income distribution, but it is also accruing disproportionately to a few racial groups.” The result, according to the researchers, is “a rigid income structure wherein [B]lacks, Hispanics, and American Indians may move within their own income distributions but still are stuck at the bottom overall.”

Lack of opportunity and economic mobility for Black, Hispanic, and American Indian adults didn’t come about by chance. They’re the result of both past and ongoing racial discrimination, including persistent discrimination in hiring, the shutting out of Black families from neighborhoods of opportunity even as white families received federal subsidies to enable wealth-building through movement to new suburban homeownership, the exclusion of mostly Black and Latinx farmworkers from the protections of labor laws and social security, the protection of almost all-white suburbs from being required to share resources and classrooms with nearby mostly-Black cities, and the attack on American Indian families and culture through coercive boarding schools that have all contributed to the present situation.

Even as many Black, Hispanic, and American Indian adults are stuck in the roughly 20 percent of the population (or quintile) with the lowest income, the quintiles themselves are moving farther apart. A number of studies have found widening inequality for the U.S. population as a whole since the 1970s, with more of the total income going to a small number of households at the top. The new Demography study adds to that literature by finding increasing within-race income inequality for working-age adults in the United States. Within each racial group, adults at the top of the income scale saw their income grow faster between 2000 and 2014 than those in the middle of the income scale. And, particularly among white people, those at the bottom fell even farther behind those in the middle. This means that, to the extent that adults measure their incomes against other people of the same race as themselves, lower-income people of all races, but especially white people, are likely to be experiencing increasing levels of anxiety about falling farther behind. It also means that, contrary to some assertions, rising inequality in the United States is not solely the result of increasing racial diversity.

There are a number of concrete steps policymakers could take here in Virginia to expand opportunity for communities of color and low-income families. Recently, legislators met for “reconvened session” to consider a set of amendments that included proposals to make Virginia’s one-time refund checks fairer for low-income working families, invest in affordable housing, restore access to driver’s licenses for individuals who faced suspensions due to unpaid court fines and fees, and make sure every Virginia community was fairly counted during the 2020 Census. While only a few of these proposals were agreed to by the majorities of both the House and Senate, they show that concrete steps forward can be taken.

And legislators can do more – today’s and tomorrow’s leaders can choose to make transformative investments in affordable housing in communities of opportunity and make sure families of color aren’t once again locked out of the new housing investments. We can fund programs for low-income homeowners to make improvements to their homes to reduce their energy bills, with a focus on providing jobs for returning citizens and individuals living in high-unemployment areas. We can pay state employees and employees of state contractors a living wage. We can invest in need-based financial aid for students at Virginia public colleges and universities. We can make sure every Virginia school has the resources it needs to give every child the opportunity to reach their full potential. We can provide resources to track and begin to understand and address the fiscal, equity, and justice impacts of Virginia’s youth and adult jails and prisons. And to fund this, we can ask those who are the economic winners to contribute their fair share in taxes.

Category:

Economic Opportunity