July 13, 2020

Pandemic Exacerbates Health and Economic Concerns for LGBTQ People of Color

Everyone should be able to access health care and take needed time off to care for themselves or loved ones without fearing for their livelihood – the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored this need. Many people across the commonwealth are experiencing significant challenges in this moment, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trangender, and queer and/or questioning (LGBTQ) communities, particularly LGBTQ people of color, face additional barriers to critical supports such as income, health coverage, and paid leave. In recent months, policy victories at the state and federal level have made important strides toward equality for the LGBTQ community. Yet Virginia lawmakers must take additional steps to address both the basic and unique needs of LGBTQ people of color highlighted by the current health and economic crises.

Discrimination in hiring, health care, and housing place LGBTQ people of color at higher risk of serious complications from COVID and higher rates of economic instability due to lost jobs during the pandemic. In Virginia, LGBT people are more likely to be unemployed, uninsured, and food insecure, and are more likely to have income less than $24,000, compared to non-LGBT adults. Around 40% of LGBT individuals in Virginia are people of color, a group that has been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. While people of color make up just 39% of Virginia’s population, as of July 7, 72% of confirmed COVID-19 cases with race/ethnicity data are people of color. Unequal health and economic outcomes have long been an issue and may have been compounded by the economic and health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. And for those who face discrimination along multiple axes of inequality, such as LGBTQ people of color, these impacts can be even more severe.

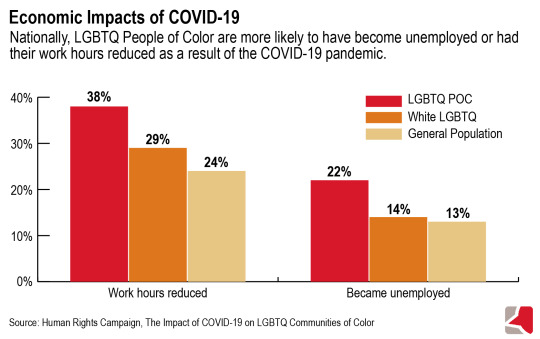

Nationally, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating economic impact on LGBTQ communities of color – 38% of LGBTQ people of color have had their work hours reduced, compared to 29% of white LGBTQ people and 24% of the general population, and 22% of LGBTQ people of color became unemployed, compared to 14% of white LGBTQ people and 13% of the general population. LGBTQ people of color are also more likely to have asked for delays in paying bills (19%, compared to 14% of white LGBTQ people and 12% of the general population) and rent (14%, compared to 8% of white LGBTQ people and 7% of the general population). This indicates that the pandemic has taken an immense economic toll on LGBTQ people of color.

This economic insecurity could be due in part to the fact that people who are LGBTQ are more likely to work in industries that have been highly impacted by efforts to stop the spread of COVID-19, such as food service or restaurants, and are at high risk of losing shifts or jobs. And a higher likelihood of LGBTQ people in Virginia earning below $24,000 annually could also result in living paycheck to paycheck and being unable to put away money to deal with reduced or loss of income due to COVID-19.

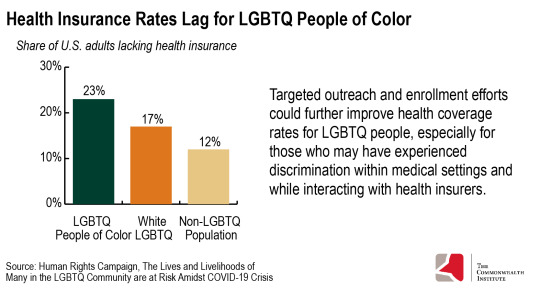

In addition to the economic burdens resulting from COVID-19, access to medical care is a significant concern. Nationally, one in five LGBTQ adults, including 23% of Black LGBTQ adults and 24% of Latinx LGBTQ adults, have not seen a doctor when needed because they couldn’t afford it. LGBTQ people, particularly LGBTQ people of color, also lack health insurance coverage at a higher rate (17%, including 23% of LGBTQ people of color) than the non-LGBTQ population (12%).

Discrimination also acts as a barrier to health care access for the LGBTQ community. Nationally, 16% of LGBTQ respondents say they have been discriminated against by a doctor or health clinic based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, and 18% say they have avoided going to a doctor or seeking health care because they were afraid of discrimination. These factors can lead to avoidance of medical care and the worsening of health concerns that affect LGBTQ people and Black people at higher rates, such as asthma, and put them at an increased risk of complications related to COVID-19.

Finally, lack of access to paid medical leave is a problem for many working adults, and presents a particular challenge to LGBTQ workers, many of whom have low incomes and therefore may not have the savings to weather an unpaid absence from work. In a 2018 survey, only 29% of LGBTQ respondents reported having access to a paid leave program through their workplace for personal medical reasons. Access to paid leave is crucial for families with low wealth who may not have the resources to take extended unpaid time off. The status quo forces too many working people to choose between their health or taking care of a loved one and paying for essentials like housing and food. No one should be forced to make that decision.

During the 2020 session, the Virginia General Assembly passed Senate Bill 868, prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations, housing, and employment on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Additional legislation provided protections against discrimination in state-regulated health insurance plans and other important areas. And in June, the United States Supreme Court decided that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects employees from being fired for being gay, lesbian, or transgender. While these choices may be significant in moving Virginia toward being a more inclusive state, as communities of color well know, formally prohibiting discrimination does not end it, nor does it undo the harms of past discrimination. Virginia lawmakers must do more to meet both the basic and unique needs of LGBTQ people of color.

Similarly, although progress has been made in extending health insurance access to more LGBTQ people in Virginia, additional work remains. The Affordable Care Act included important coverage expansions for low-income people – a group that includes many LGBTQ people – and also provided new non-discrimination rules. Since its implementation, the rates of health insurance coverage for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals has increased at the national level, including through increased enrollment in Medicaid. (The most recent Virginia data on health coverage for LGBTQ people is prior to the state’s implementation of Medicaid expansion in January 2019.)

However, targeted outreach and enrollment efforts could further improve health coverage rates for LGBTQ people, especially for those who may have experienced discrimination in medical settings and while interacting with health insurers. Key strategies such as partnering with LGBTQ community organizations, developing LGBTQ-specific materials and messages, and distributing information at LGBTQ community events could help Virginia to connect more members of the community with coverage options.

Cultural competency and cultural humility training are also necessary steps toward providing equitable medical care for LGBTQ people of color. Together with cultural competence, which emphasizes awareness of and being responsive to cultural differences, cultural humility calls on health care professionals to self-evaluate, recognize their own biases, and to address the power imbalance of the provider-patient relationship. This approach could help to better treat patients from diverse backgrounds and reduce disparities in care. Virginia should take a step in this direction and join the 10 states that already require cultural competency training for physicians, surgeons, physician assistants, nurses, and/or therapists in order to provide essential care that centers the lived experiences of people and communities.

Additionally, members of the LGBTQ community need access to paid time off to care for themselves and loved ones, both during and beyond the threat of the pandemic. The federal government implemented a temporary paid sick program and a paid child care leave program through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA). Lawmakers in Virginia should go further by enacting a statewide paid family and medical leave program. Such a program would provide workers with low incomes and workers of color – groups with historically less access to paid leave – the opportunity to take the necessary time off to care without having to worry about losing their jobs or income. Such a program should recognize and include a variety of family structures, including the familial relationships that LGBTQ people often form in the face of loss of bonds with parents and other birth family members.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exhibited the ways societal and interpersonal discrimination impacts the economic and health outcomes of marginalized communities such as LGBTQ communities of color. In their response to COVID-19, state lawmakers must actively acknowledge and work to address the systemic barriers which place LGBTQ people of color at greater risk of detrimental economic and health outcomes and move Virginia toward becoming a more inclusive and equitable place to call home.

Categories:

Economic Opportunity, Health Care