August 17, 2021

Use of ARPA Funds a Step Forward, More to be Done to Build a Just Future

Everyone in Virginia deserves the opportunity to recover from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the Black and brown communities that have been hardest hit over the last two years. Coupled with generations of policy decisions that created racial inequities long before the COVID-19 pandemic, lawmakers must continue to center racial justice in funding decisions.

The final budget approved last week, which appropriated $3.5 billion in federal funding from the American Rescue Plan Act, advances a number of initiatives that begin to address inequities across Virginia. Still, more must be done in the upcoming 2022 regular legislative session to make sure everyone in Virginia has the opportunity to thrive. On Wednesday, August 18, Virginia’s Secretary of Finance will report on the state’s finances for the fiscal year that ended on June 30 and provide a preview of what we can expect for the current fiscal year and the following ones. As we look back on how Virginia policymakers used the bulk of the flexible ARPA funds, it’s important to also look forward to how Virginia can more fully meet the needs of communities in an ongoing way.

How are state policymakers using the American Rescue Plan Act funds?

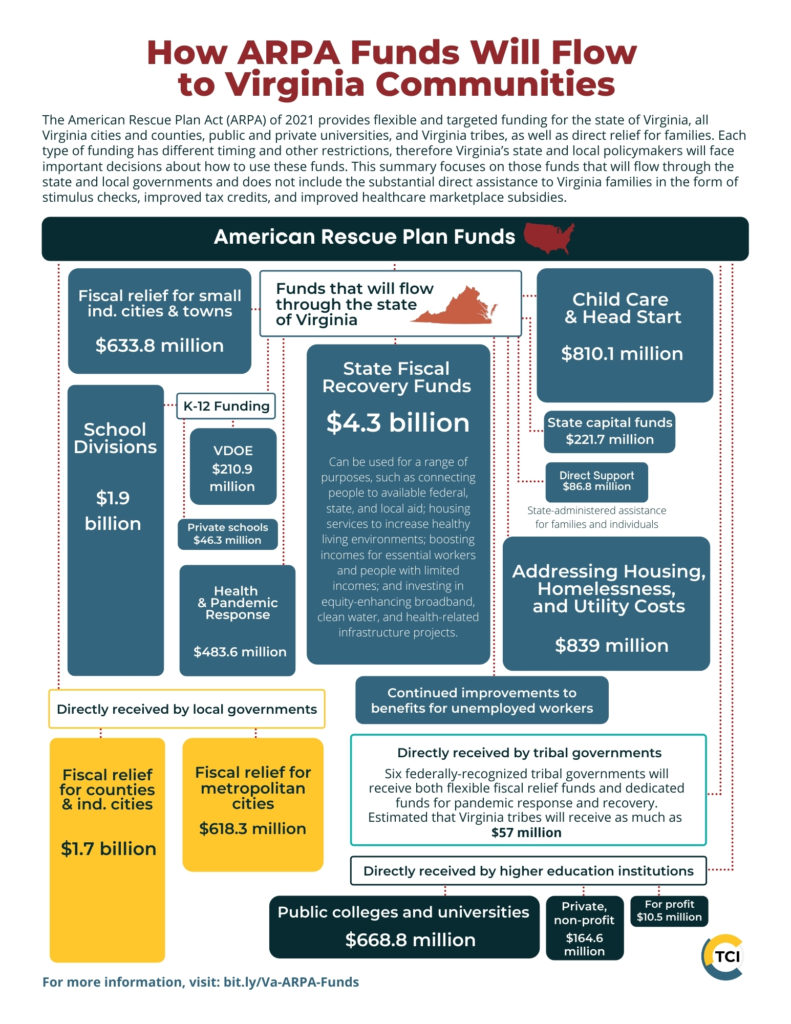

Virginia’s House of Delegates, Senate, and governor recently agreed on how to spend $3.5 billion of Virginia’s $4.3 billion of flexible funding provided by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Below is a summary of the major decisions on uses of the flexible funds and their racial equity impacts. Additionally, state policymakers appropriated $5.7 billion for stabilizing and improving child care services, supporting public education, helping local governments, investing in mental and behavioral health, and other services.

- Utility assistance ($120 million). This is much-needed assistance that should help families who have faced financial hardship due to the pandemic and recession. Because low-income families and families of color often cannot afford to rent or buy energy-efficient homes (or pay to upgrade their existing homes to be more energy-efficient), many face high energy bills on top of already struggling to make ends meet. Data from before the pandemic showed that 2 out of every 3 low-income households faced a high energy burden, and Black, Hispanic, Native American, and older adult households face particularly high energy costs compared to their incomes.

- Sewer systems and other water quality improvements ($305.8 million). Much of this funding is dedicated to helping cities with aging infrastructure upgrade their systems, which will help the water quality of the state as a whole. Included is $50 million for Richmond City, $50 million for Alexandria, and $25 million for Lynchburg for combined sewer overflow control projects. Due to barriers to suburban homeownership for many Black families and ongoing barriers to housing options for families of color more generally, taken together these cities are home to a high number of residents of color compared to the population of the state as a whole.

- Broadband ($718.7 million, including $497 million of flexible ARPA funds and $221 million of ARPA capital funds). One of the largest investments made during the special legislative session was for increasing broadband services throughout the state. As more families have had to learn and work from home since the pandemic began, high speed and reliable internet access has become an essential resource. Of the more than $700 million appropriated for broadband, only $16 million of it is reserved to address affordability for families, while the rest is slated for expansion of service to places that currently lack high-speed access. While connecting families to high-speed internet is critical, Black and Hispanic households in Virginia are much more likely than white households to lack internet due to affordability challenges. In Virginia, 12% of all white households lack a subscription to the internet or any computing device. For Hispanic households, that number rises to 15%, while for Black households, the number is almost twice the amount as white households, at 22%. For households with computers, Black households are nearly twice as likely to lack access to broadband (higher speed) internet subscription than white households.

Overall, making broadband available in more areas of the state is one part of the equation for connecting families, but this budget fails to adequately account for the other part of the equation—affordability—and in doing so leaves too many Black and Hispanic households disconnected. Should Congress pass a federal infrastructure bill that includes funding for broadband, Virginia’s policymakers should use this new restricted funding to expand broadband infrastructure, and at the same time, free up and redirect the more flexible ARPA support to tackle affordability challenges. State lawmakers should also explore opportunities during the 2022 legislative session to find long-term solutions that ensure all Virginians can afford this essential service. - School infrastructure ($250 million). Since ARPA passed in March, state advocates have been calling for the equitable distribution of this funding to assist schools with urgent school infrastructure challenges. It’s well known that much of our school infrastructure in high-poverty areas is dilapidated, impacting student and staff outcomes, and represents an ideal investment opportunity for one-time federal aid. Unfortunately, state lawmakers took a narrower path and invested $250 million to upgrade school HVAC systems and added a contingency for a local one-to-one match of the funds. This approach diverges from typical state aid for K-12 schools, which usually applies formulas that account for student need and a locality’s ability to raise local funds. Consequently, school divisions with the fewest local resources and greatest student need are in the worst position to take advantage of this one-to-one state match program for upgrading their HVAC systems.

- Behavioral health ($246.6 million). The pandemic has taken a mental and emotional toll on many, straining an already inadequate and understaffed behavioral health system in Virginia. Deficiencies in Virginia’s mental health safety net have an outsized impact on Black individuals in Virginia with Black patients making up nearly 28% of all people serviced by Virginia’s mental health system. State mental health hospitals regularly surpassed capacity levels considered safe prior to the pandemic and increased need along with low staffing levels led five of the nine state mental health hospitals to halt new admissions in July 2021. Legislators dedicated $121.9 million to increasing wages of employees at state behavioral health facilities in the hopes of attracting and retaining qualified mental health professionals. Another $40 million was appropriated to expand community based mental health and substance abuse services in order to provide interventions prior to emergency situations that would require hospitalization. These long-needed investments are a step in the right direction, however more could have been done to ensure all Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services (DBHDS) staff are adequately trained to meet the needs of people of color in Virginia. The legislature failed to fund a $1 million request from DBHDS to fund ongoing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion training for its staff.

- Unemployment Insurance ($862 million trust fund deposit to offset future employer taxes; $91 million for information technology modernization, call center improvements, security, and claims adjudication). Many families continue to struggle financially with the effects of the pandemic and recession, given the number of unemployed workers and indicators of family hardship—such as not having enough to eat—remain high. Job losses remain greatest in low-wage industries, concentrating the hardship among those who were already most financially vulnerable, and nationally, 8.2% of Black workers and 6.6% of Latino workers were unemployed in July. The overall unemployment rate was 5.4%, up from 3.5% before the pandemic. Unfortunately, Virginia’s use of flexible funds for the unemployment insurance system is mostly dedicated to offsetting employer taxes, rather than improving benefits or the still-troubled benefit administration system.

- Support for businesses ($250 million for Rebuild VA; $110 million for tourism and other economic development support). Despite historically facing barriers to accumulating wealth and borrowing, both of which are important to starting and sustaining businesses, people of color owned 32% of businesses in Virginia in 2017, only slightly below the share of Virginia’s overall population that is people of color. Unfortunately, Black-, Latinx-, and Asian American-owned businesses are highly concentrated in the industries that faced the largest job losses from the pandemic. The pandemic was particularly challenging for Black-owned businesses. The five most vulnerable sectors – including leisure, hospitality, and retail – make up 25% of the revenues of all U.S. businesses, but 40% of the revenues of Black-owned businesses. While the number of active business owners in the U.S. dropped by 22% from February to April 2020, the number of Black business owners dropped by 41%. Furthermore, a lack of preexisting banking relationships barred or delayed many Black business owners from accessing funds from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). The Rebuild VA program has a priority of reaching small businesses and nonprofits. Currently, the state reports that 32% of Rebuild VA funds have supported businesses owned by people of color, similar to the share of Virginia businesses owned by people of color. It’s not clear if the ARPA money for the tourism industry and other business development has the same prioritization of smaller businesses, and Black and brown Virginians are less likely to own larger businesses (those with employees). Nearly 80% of Virginia businesses with employees are owned by non-Hispanic white people.

For generations, support systems that lifted us all up—like our schools, social service programs, and more—have been underfunded. But a new future is possible.

- Legal representation for people facing eviction ($2.5 million). Policymakers provided a small amount of money to increase access to legal representation for people facing eviction. Black and Latinx families are most at risk of eviction and foreclosure. This is due to both past and present discrimination leading to lower incomes and lower wealth, as well as ongoing direct discrimination on the part of landlords and lenders. Most landlords are represented by lawyers in eviction proceedings, but tenants rarely have representation, leaving them at a disadvantage. This funding will help a slightly larger proportion of tenants have access to counsel. Additionally, the budget renewed until June 30, 2022 Virginia’s requirement that before filing for eviction, landlords take certain reasonable steps to access the rent relief program before evicting a tenant for not paying rent.

- Language access ($0.5 million). Policymakers provided $500,000 for the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion to contract consulting services for their report on how Virginia can expand language access across state agencies. This is a good first step to completing a comprehensive report so that the estimated 212,000 people in Virginia who report having limited English proficiency (LEP) can meaningfully access state services and information. LEP individuals in Virginia have faced substantial obstacles during the COVID-19 pandemic, with many unable to understand the constantly updated policies regarding unemployment insurance, workplace safety, education, and more. The final report is due to the governor and General Assembly by November 1, 2021. Lawmakers should take the recommendations of the report to establish strong language access policies across state agencies and provide the necessary funding to ensure meaningful access for LEP families in Virginia. Thousands of Latinx and Asian American and Pacific Islander residents who have had limited access to important COVID-19 related information are relying on lawmakers to act boldly and quickly.

- Law enforcement bonuses and raises ($40 million for state police; $33 million for state-supported sworn officers of Sheriff’s Departments and Regional Jails; $24 million for state prison staff). State policymakers included $97 million of ARPA money for bonuses and, in the case of state police, ongoing raises for a variety of state and local law enforcement personnel. People of color are under-represented in law enforcement and therefore will be less likely to benefit from these raises.

- Appropriation of Dedicated Funds: State lawmakers appropriated about $5.7 billion that the state will receive from ARPA for particular purposes identified in the federal legislation. This includes $2.1 billion in emergency relief funds for K-12 public schools, $807 million for child care, $667 million for emergency relief funds for public and nonprofit higher education institutions, $557 million in implementation grants for the unemployment system, $465 million for emergency rental assistance, and $90 million for low-income home energy assistance.

Looking ahead to the 2022 legislative session and beyond

Virginia’s next set of critical decisions will be about how to use Virginia’s own resources — the money we currently raise through income and sales taxes and fees, and the money we could raise from fixing our upside-down tax system — to invest in a more equitable and prosperous commonwealth.

The pandemic has underscored the indispensable role that schools play in our communities. Virginia made some progress in 2021, giving a conditional 2-5% pay boost to teachers and staff, maintaining funding for divisions that had temporary enrollment losses, and making use of the earlier federal aid packages to provide need-based academic aid to schools. These investments might keep schools functioning and provide remediation services to students in the short term, but policy makers must also address larger scale structural problems that Virginia faces, including having the least competitive teacher pay in the country, being 41st for state per pupil P-12 investment, and potentially needing nearly $25 billion of upgrades to school infrastructure. These have become perennial issues in Virginia, made worse by the fact that lawmakers never fully restored funding that was cut a decade ago during the Great Recession. Transcending these challenges will require bold and sustained investments across the board in P-12 education in the 2022 legislative session and beyond.

The pandemic and recession has also raised attention to the longstanding barriers to affordable and stable housing. Public policy decisions in the past opened the door to homeownership for many white families in Virginia through access to affordable federally-backed mortgages and building highways that allowed new suburban residents to quickly get to jobs. Those doors were closed to most Black Virginians, however, and growing numbers of Virginians of all races are facing rising rent and home prices that consumes an unaffordable share of income for families. More than 380,000 Virginia families pay more than half their income for housing costs, and almost 900,000 — or 1 in 4 Virginia households — pays more than 30% of their income toward housing, a level that the US Department of Housing and Urban Development considers unaffordable. It’s past time for Virginia to do its part to open homeownership opportunities for Virginians and their children who were deliberately excluded through past policy choices, while also supporting the development of affordable rental housing in communities of opportunity and repairing some of the damage of past transportation policy decisions.

While smart federal policy decisions are contributing to a jobs recovery, returning to baseline isn’t good enough.

And while smart federal policy decisions are contributing to a jobs recovery, returning to baseline isn’t good enough. Before the pandemic, too many working adults in Virginia were stuck in low-paid, unstable jobs without a meaningful pathway to a more secure future. And too many young people who have made the decision to pursue higher education have been left with high levels of debt due to college costs growing faster than incomes. Virginia has begun investing more in higher education affordability, including community colleges. These investments could be supplemented by programs, such as summer jobs programs for teens and energy-efficiency upgrades to homes, that invest in our communities while creating good jobs that provide a meaningful path into or back into the labor market, particularly for workers who face extra barriers even in good times.

The state can also help families thrive through smart use of refundable tax credits for low- and moderate-income families. The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC) are proven tools to boost family incomes. Virginia provides a state EITC up to 20% of a family’s federal EITC. Unlike the federal EITC and nearly all state EITCs, Virginia’s EITC is “nonrefundable” and a family’s credit is capped at the amount of state income tax owed. Removing this limit would boost incomes of qualifying families by several hundred dollars on average, and would be one step toward a more equitable tax system. Refundability would help to increase incomes for working families across the state, particularly Black and Latinx families, and would help to address long-standing wage gaps that persist for Black and Latinx working people. Virginia could also enact a refundable CTC to boost family incomes even further and help families better afford basics like childcare, transportation, and food.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only put a direct spotlight on the already existing inequities that have disproportionately hurt Black and brown families across Virginia, it drastically widened racial inequality. For generations, support systems that lifted us all up—like our schools, social service programs, and more—have been underfunded. The weakening of these support systems meant that families with means could more easily navigate the public health pandemic, while those without were pushed further behind. But a new future is possible. The General Assembly can continue the progress made to advance racial justice through the budget by fully investing in programs that will give everyone in Virginia the opportunity to thrive. That will only be possible if lawmakers center those most impacted by racial inequities and boldly raise new sustainable revenue to continue these transformative investments.

Categories:

Budget & Revenue, Economic Opportunity, Education, Health Care