October 13, 2021

Changing Gears: Addressing Virginia’s Persistent Lack of Support for English Learner Students

Executive Summary

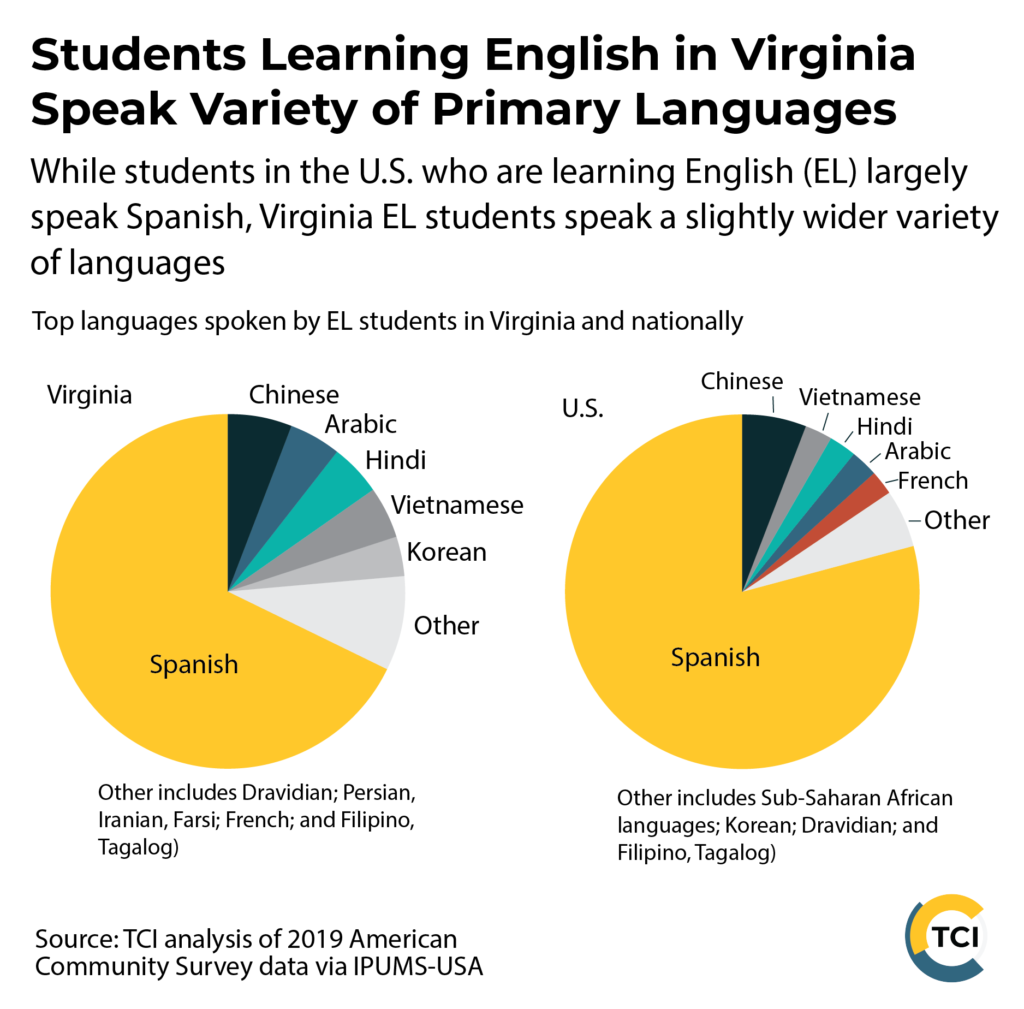

Every student should have access to a high-quality education. Yet new analysis finds that Virginia’s English Learner (EL) student population faces significant barriers to education and the state is falling short in providing adequate resources to assist students in overcoming these barriers. With around 1 in 10 Virginia K-12 school students classified as EL, Virginia is now on par with the national average for representation. EL students are diverse and are more likely to speak a language other than Spanish, compared to EL students nationally.

Virginia provides relatively low and inadequate support for EL students, and has among the lowest achievement levels nationally. Findings include:

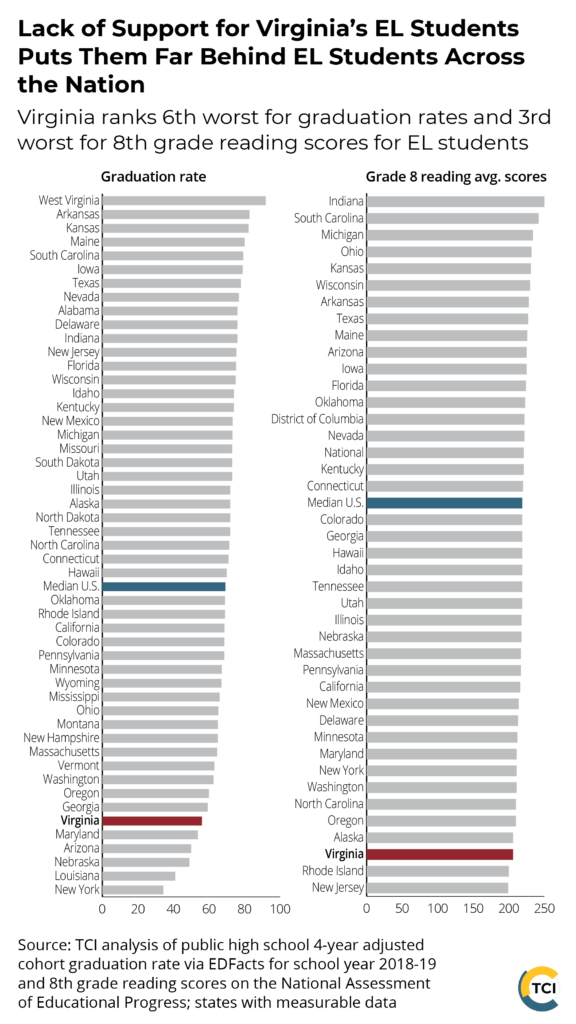

- Virginia ranks 6th worst in the nation for EL graduation rates, and 3rd worst on the 8th grade National Assessment for Educational Progress test.

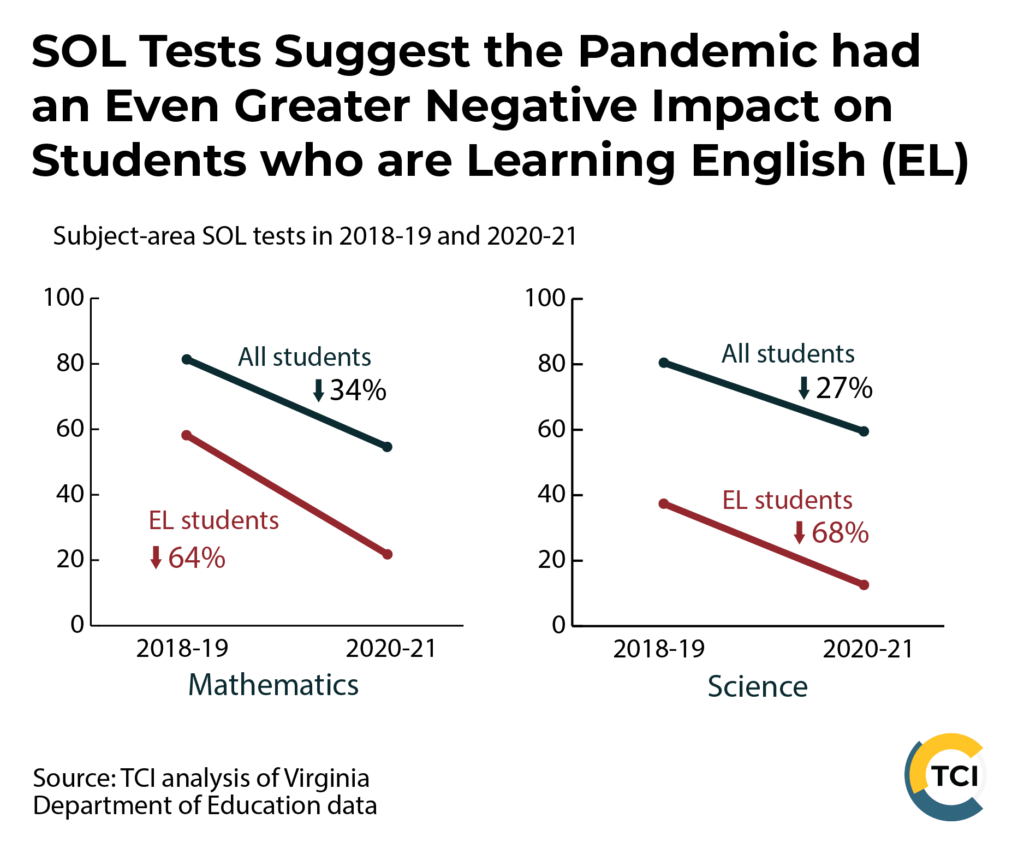

- EL students in Virginia have faced unique challenges during the pandemic and have had the most significant drop in state achievement scores of any student groups measured for state reading, math, and science tests.

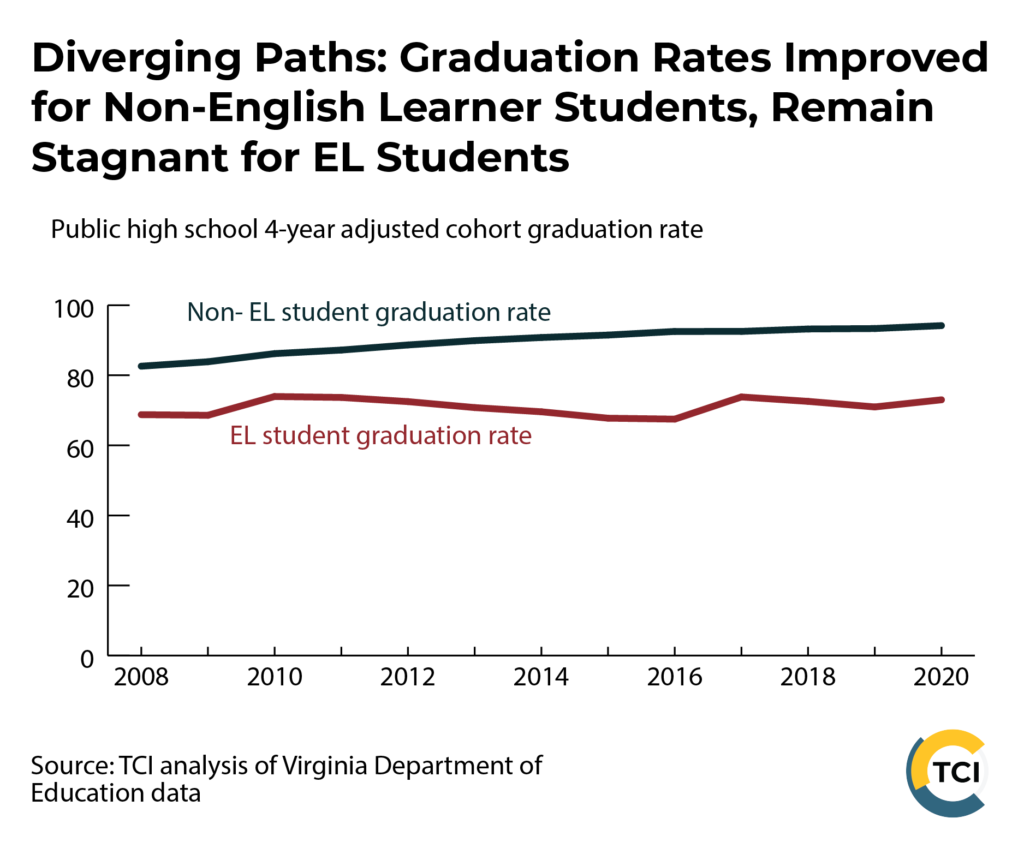

- Graduation rates for Virginia EL students have been stagnant for much of the past decade, while non-EL students have seen continual improvements.

- Virginia EL students are less likely than peers to be identified for gifted education programs, are similarly less likely to graduate with Advanced Studies Diplomas, and are among the least likely group of students to enroll in higher education opportunities beyond high school.

Evidence for these outcomes, particularly over the pandemic shows that EL students are not receiving adequate support to overcome barriers they face. Parents and guardians of EL students are less likely to have easy access to school information in their native language. EL students were also more likely to have experienced economic, health, and emotional hardship over the pandemic, along with regression in language proficiency and will need additional support in school settings to navigate these challenges.

Several policy solutions are available to improve EL student outcomes in Virginia, including new estimates on adequate state-level supplemental support. For the 2021-2022 school year, the state provided an additional $725 per EL student, which represents a 13.5% state supplement — a low level of support compared to the national average of 39%. Based on adequacy studies from other states, which range from 35% to 41% of supplemental support, offering comparable lower-bound estimates of similar levels in Virginia would provide an additional $132 million to $169 million a year in support for EL students. Virginia EL students would significantly benefit from the state increasing targeted support to more adequate levels and making it more flexible. The state should take the next step and commission a review to determine the higher and more appropriate level of support needed to adequately fund EL services.

A number of other solutions will address barriers to learning, including:

- fully funding the revised Standards of Quality, as recommended by the Virginia Board of Education, which include a number of investments from additional EL instructors, to support staff such as social workers, nurses, mental health practitioners and reading specialists;

- scaling services for EL students rapidly by investing in community-based organizations that serve EL students and immigrant families;

- providing state funding to support community school models, which provide holistic support at the school site. This comprehensive approach helps meet the basic needs of students and families, allowing them to better focus on education and succeed in school.

The state could also advance policies that help to identify and nourish the strengths and abilities of EL students, and stem troubling trends, including the lack of EL students earning Advanced diplomas and teacher pipeline challenges. For example, automatically enrolling qualified students in advanced courses with an opt-out option, an approach that is in use across the country, has been shown to reduce tracking and selection bias, and get more qualified students on advanced studies tracks. In addition, the state could invest in dual language instruction and out-of-school programming that is shown to improve EL student academic outcomes. Core to EL students succeeding in any of these classes or programs are trained staff to work with students learning English. The state could do much more to incentivize a pipeline of diverse teachers by offering direct support to education and certification programs to lower the barrier to entry.

English learner (EL) students are officially designated within schools as students who are not fully proficient in English and need additional services. Students can place out of the EL designation once they demonstrate proficiency.

Introduction

Every child should have access to an excellent education, and in Virginia, it is written into the state constitution that the legislature will seek to ensure “an educational program of high quality.” Year after year, the state underfunds EL students, resulting in lower achievement in graduation, testing, and higher education enrollment outcomes for this fast growing segment of the student population. And while EL students face significant barriers to learning in other states, Virginia fares poorly on a national scale for EL student achievement. The barriers that EL students face have been exacerbated by the pandemic, and data suggests they have been hardest hit by the disruptions.

Increased funding alone will not solve all of these alarming outcomes, but it is an essential part of the equation. Comprehensive research on school funding over the past decade has led to the inescapable conclusion that funding makes a significant difference over time for achievement, graduation, and higher education enrollment outcomes.1 It is time for state leaders to make significant changes in how Virginia funds staffing and services for EL students to reverse recent increases in dropout rates, meet the promise of providing a high-quality education to all students, and move us out of the bottom tier nationally for EL student outcomes. Other states have gone through the process of determining adequate support levels for EL students and have made changes. Virginia should follow suit.

Virginia EL Students are Diverse, Speak Many Languages, and Live Across the State

Diverse learning environments are beneficial to all students, and spoken languages contribute to that diversity. Virginia is home to speakers of many languages, and English learners (EL), sometimes referred to as multilingual learners or English language learners, are a rapidly growing group of K-12 students in Virginia. Ten percent of students in the state are identified as English Learners, having caught up with the percentage of EL students in the nation.2

However, the density of students across the state differs significantly. The five divisions with the most EL students are all in Northern Virginia: Fairfax County, Prince William County, Loudoun County, Arlington County, and Alexandria City. Fairfax County has the greatest number of EL students out of all school divisions, with around 37,000 EL students enrolled in the 2019-2020 school year, out of 116,000 statewide.3

Looking at EL students by share of total student enrollment, the top five localities are still concentrated in the Northern Virginia region, with the exception of Harrisonburg City. Manassas Park City has the highest share of EL students (34%) out of all localities, followed by Harrisonburg City (33%), Manassas City (33%), Alexandria City (31%), and Winchester City (21%).4

It is important to note a wide variety of school divisions all across the state have relatively high shares of EL students as parts of their student bodies. For example, 15% of Accomack County’s student population are EL students, as well as 13% of Richmond City’s and 11% of Charlottesville City’s student population.5 Policy solutions, including funding, should take into account the dispersion of EL students throughout the state.

Race & Ethnicity

Similar to national trends, Virginia’s student population has diversified considerably over the past 15 years, and students of color make up a majority (52%) of all students statewide. EL students are equally diverse as a group. Although these students have learning a new language in common, they come from a variety of backgrounds, have diverse experiences and needs, and a wealth of cultural and social resources to share with peers. Students of color make up the large majority of EL students (around 90%).6

While the share of EL students who are students of color remains unchanged over the last decade, the race and ethnicity of EL students has changed somewhat. Today, Latinx students make up the majority of EL students (70%), up from 61% in the 2008-2009 school year. Asian American students make up the second largest share of EL students at 14%, and white students make up 9%.7

Languages Spoken

Because race and ethnicity do not always correlate to a specific language spoken at home, it is important to recognize that EL students speak a variety of languages. For some students, English may not even be their second language.

Spanish is the top language (60%) spoken by public school students in Virginia who speak English “less than very well,” according to Census data. Compared to the United States overall, EL students in Virginia are more likely to speak a language other than Spanish — nationally, 71% of EL students speak Spanish. Around 25% of Virginia EL students speak a variety of Asian languages with Chinese, Arabic, Hindi, Vietnamese, and Korean being the top languages spoken after Spanish. Around 14% of students nationally speak Asian languages, with the most common being Chinese, Vietnamese, and Hindi.8

While the diversity of languages spoken may present challenges in meeting every student’s needs, making sure that instruction as well as outreach to families is as accessible as possible allows for richer participation and engagement.

Virginia EL Student Outcomes in Context

Many factors contribute to an EL student’s achievements or challenges in school, including state and local funding, diversity of language, density of EL students within school divisions, state support services provided for immigrant families, school structures and available courses, and strength of community-based organizations to name a few. Developing a deeper understanding of the barriers that EL students face is essential before considering state policy solutions. This report does not seek to provide an exhaustive review of all potential barriers impacting EL student outcomes, but rather focuses on selected measures that are most likely to inform state policy conversations and solutions.

National Comparisons Show Virginia Does Little to Help EL Students Overcome Barriers to Education

EL students come to Virginia schools with a wide range of educational and cultural backgrounds, English fluency, and household resources and responsibilities, along with individual hopes and aspirations. Yet it is clear based on state data that a majority of EL students are not receiving the support they need to overcome unique barriers to education.

While this trend is not unique nationally, Virginia fares particularly poorly compared to other states — ranking 6th worst for EL graduation rates,9 third worst out of all states with measurable data for 8th grade EL student reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), and below average for math scores.10 Virginia has seen among the largest drops in academic achievement on the NAEP across both math and reading over the past decade of any state.11

There are many likely contributing factors that influence Virginia’s low achievement scores for EL students. General state funding likely plays a large role, with Virginia providing significantly lower targeted support for EL students than the national average (discussed in detail in Solutions section). Also, the state of Virginia covers few of the additional costs to provide a high-quality education for EL students beyond the state share of salaries for a limited number of EL specialist instructors. This leaves it up to school divisions to fund professional development for general education teachers who work most with EL students and procure educational resources in multiple languages or that are specifically designed for students learning English. Funding alone can not explain the full picture of why Virginia’s EL students consistently rank in the bottom tier on national academic assessments, yet it remains a critical place to start.

Beyond lack of funding, with such low achievement on a national scale, it is reasonable to ask whether families of Virginia EL students are uniquely disadvantaged compared to peer families in other states — Census data suggests this is not the case. While not a perfect proxy for families with EL students, the most recent five-year aggregated Census data shows that Virginia foreign-born headed households with children under 18 have among the lowest poverty rates of all other states, and foreign-born residents over 25 are more likely than their peers in most other states to have attained a high school diploma.12 These statistics fall short of perfectly capturing the circumstances of families with EL students, but do indicate that Virginia’s uniquely low EL student achievement can not be explained by the poverty status of likely families with EL students or the educational attainment of their parents. The lack of adequate resources and supports within Virginia schools likely plays a more significant role in contributing to the relatively low national standing.

Low Graduation Rates and Other Measures Show Urgency of Improving Services for EL Students

At the state level, EL students consistently have the lowest pass rates on state tests for reading and science of any student subgroups that are measured, including students experiencing homelessness, students with disabilities, and students from households with low incomes. They normally have the lowest or next to the lowest pass rates for mathematics. Between the last two implemented state Standards of Learning (SOL) exams given in 2019 and 2021 (exams were not required in 2020 due to the pandemic), EL students saw the largest percentage drop of all recorded student groups in reading, math and science exams.13

It should be noted that up to a quarter of students opted out of various SOL tests in 2021 and there were increased logistical challenges for completing these exams since they had to be done in person. The sample size of students taking the tests was still a substantial share of Virginia’s student population, however, there might be assumed selection bias in some of the results based on students from households that were more or less likely to allow their children to take these assessments in person.

The 2021 SOL declines were in line with other statewide assessments, such as the PALS reading assessment, implemented in almost all divisions in grades K-2.14 The PALS results show that as of 2021, a majority of EL students in each of the three early grades measured are now at risk for persistent reading difficulties moving forward. Even before the pandemic, young Virginia EL students had among the highest likelihood to be at risk of ongoing reading difficulties. For years, education experts appointed to the Virginia Board of Education (VBOE) have recommended increasing the number of reading specialists in Virginia schools and setting a minimum ratio to students.

Lawmakers have yet to meaningfully consider proposals that act on this recommendation, despite the consistent barriers that EL students and other student groups face to higher achievement in reading. The VBOE as of fall 2021 is considering going further in their recommendation to increase reading specialists in schools, making this one of their top recommendations and suggesting these specialists focus support on students that fail their third-grade reading diagnostic. Since EL outcomes in the PALS assessment indicate need for additional reading support, this VBOE recommendation would provide much-needed assistance. Without intervention, the long-term implications of the worsening PALS reading results for EL students is troubling, especially since early literacy rates are a strong predictor of long-term academic achievement.15

Virginia EL students in high school also face unique barriers. Lack of school counselors who speak multiple languages, accessible school resources for parents and guardians who may have limited English fluency, and overall inadequate academic support likely all contribute to low graduation rates for Virginia EL students. Dropout rates have remained stubbornly high in Virginia, particularly for EL male students (around 29% in 2020),16 with some reasoning that this is due to a need to find employment to help support themselves and their families. Many immigrant households may not qualify for public benefits, even if they are experiencing poverty, and that could place additional pressure on working age children to help make ends meet for the family.

Education researchers who focus on EL students have raised concerns that with increased economic hardship over the pandemic, there is a heightened risk that more EL students may drop out to support their families.17 The limited scope of state support for EL students, focusing nearly exclusively on EL teacher to student ratios, prevents this funding from going to other staff positions such as multilingual school counselors and social workers who could help students navigate options to balance school and work responsibilities and, more broadly, support students to remain in school and on a graduation track.

While non-EL students in Virginia have seen their graduation rates improve every year from 2008 to 2020 — increasing from nearly 83% to over 94% — EL student graduation rates have remained largely stagnant, oscillating between roughly 68% to 74%.18 At the school division level, differences between non-EL and EL student graduation rates can be even more stark. Disruptions caused by the pandemic may lead to more EL students not graduating on time over the coming year. Newcomer EL students in high school face major challenges in meeting high school graduation requirements, and were already at high risk of dropping out before the pandemic. Disruptions to education for EL students in high school can be particularly challenging to recover from given age-out restrictions.

Beyond simple graduation rates, we also see large differences in the types of degrees earned by EL students, who are significantly less likely to graduate with an Advanced Studies Diploma. According to research sponsored by the Virginia Department of Education, students who graduate with an Advanced diploma are nearly twice as likely to graduate or stay in higher education after four years compared to those who earn a Standard Diploma.19 Attaining an Advanced diploma entails taking advanced coursework, which may not always be available depending on the school. It is well documented that teachers struggle to identify the strengths and abilities of EL students, particularly when they have less training to work with these students, and are less likely to recommend them to advanced track and gifted programs. Indeed, Virginia recommends a lower share of EL students to gifted programs than the national average — EL students make up only 2% of Virginia’s gifted student population, even though they make up nearly 10% of the student population.20

With fewer opportunities to attain Advanced diplomas, it is no surprise that EL students are significantly less likely than their peers to enroll in educational opportunities beyond high school. Advanced coursework both prepares students better for the rigor of higher education and places students among a cohort of peers that are more likely tracked for postsecondary education. As the share of EL students graduating with Advanced diplomas has declined over the past few years, we have seen a corresponding decline in postsecondary enrollment for EL students. This has not been the case for Virginia graduates at large. This troubling trend points to the need for additional types of staff in schools to support EL student advancement and to institute policies that make it more likely for EL students to be placed on advanced studies tracks (discussed in detail in Solutions section).

“Hardest Hit”: EL Challenges Underscored and Exacerbated during Pandemic

In June 2021, the U.S. Department of Education (DOE) released an extensive report on how the pandemic has affected student well-being and outcomes.21 The DOE found that “English learners have been among the students hardest hit by COVID-19’s disruptions to in-person learning” and “for many English learners, access to adequate supports can be frustratingly elusive”. The findings reaffirm national research and fit within recent state data trends outlined earlier in this report. Current research and survey data helps us make sense of why the DOE considers EL students to be among the hardest hit students during the pandemic period.

Guiding Online Learning Was Particularly Challenging for Parents Who Are Not Fluent in English

Immigrant parents of students learning English already had unique challenges navigating the public school system before the pandemic. Federal policies and court cases since the middle of the 20th century recognized that all school-aged children have a right to a free public education, regardless of their immigration status, and parents with limited English proficiency must be provided translated communications to meaningfully participate in their child’s education.22 Yet interpretations of these rules can vary from school to school, and it’s not uncommon for parents with limited English to feel like they are not provided clear communication to best assist their children. During the pandemic, when students had to switch to remote learning, parents and guardians in many regards were expected to take a more involved role in their children’s educational process.

School divisions making the transition to virtual instruction may not have had comparable virtual resources offered in multiple languages on-hand, nor the ability to quickly transcend the digital divide. General education and EL teachers also have relatively less digital expertise to assist EL students. General education teachers are significantly less likely to be trained in providing digital resources to EL students, and EL teachers report fewer hours than their colleagues in trainings to provide digital learning resources.23 Taken together, EL students were much less likely than their peers to have support for online learning over the pandemic, which could become an ongoing challenge with more remote learning in schools.

Reduced Peer Interaction May Have Set Back English Learning

The reduction of in-person education time with peers and adults that speak English during the pandemic also raises some specific concerns around regression in language proficiency. Time during school practicing speaking English with peers, sometimes referred to as “productive talk”, has been shown to be important for fluency progression.24 At home, EL students are likely to speak their native language and may be less likely to practice as much English. Research indicates that EL students often lose ground over the summer break in their English proficiency skills,25 and remote learning may have similar impacts. A regression in English proficiency may extend how long a student is classified as an English Learner, and research shows that students who linger in EL status are less likely to graduate.26 There’s also risk for former EL students who may have placed out of EL status shortly before the pandemic. Regression in English proficiency for these students may go unnoticed and impact their ability to fully engage in school learning.

Concentrated Economic and Health Impact from the Pandemic

Aside from academic and language challenges, it is also reasonable to infer based on known outcomes of immigrant families during the pandemic that EL students were more likely to live in households that experienced more economic hardship and heightened anxiety around anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies. Immigrant families are less likely to have health coverage and may be less comfortable seeking care depending on their immigration status. Children in immigrant families are also more likely to have child care and work responsibilities, taking them away from learning time at home.27

Children in immigrant families have recently experienced an increase in trauma-induced symptoms that stem from anti-immigrant rhetoric, regardless of a parent’s immigration status.28 That’s because kids in immigrant families often can’t tell the difference between the rhetoric they hear and whether threats of deportation apply to their family. It is well documented that adverse childhood experiences, such as increased exposure to trauma during the pandemic, can have long lasting impacts on academic achievement if left unattended.29 Schools and community-based organizations can play a critical role in coordinating support services to help EL students and mitigate potential impacts on learning over the long term.

Policymakers Have Several Policy Solutions Available

More than 1 in 8 Virginia students are current EL or former EL students.30 So much of their success in school, at work, and in their community, will be predicated on the support they receive in school. Yet we know based on available state and national data that EL students in Virginia are currently not getting adequate support. There is much at stake for these students, their families, and the state of Virginia to make sure they have the opportunity to thrive, and that is going to require bold state policies and investments. Policymakers have many tools at hand to provide more adequate support to EL students

More than 1 in 8 Virginia students are current EL or former EL students.

There is much at stake for these students, their families,

and the state of Virginia to make sure they have the opportunity to thrive.

Adequate and Flexible Funding To Support EL Students

How we choose to spend shared resources in a state budget is often seen as a reflection of what and who the state values. Certainly more funding is not the singular solution when it comes to moving Virginia out of the bottom tier for EL student outcomes — how the money is spent, prioritized for students with the lowest English proficiency, and factored in with other supplementary state support for certain student groups, makes a difference. Yet based on years of comprehensive research, there is little doubt that funding matters, particularly for students who face more barriers, and has a significant impact on long-term student achievement, graduation, and postsecondary enrollment.3132 While there has been a wide range of studies in other states investigating the question of what constitutes adequate funding support for EL students, there is no doubt that current state support is substantially inadequate.

Virginia spent $668 per EL student to meet EL teacher to student SOQ staffing standards in the 2020-2021 school year and spent $5,287 per student to fund the other SOQ programs. That means the state spent about 12.6% more per EL student on SOQ costs than non-EL students.33 With recently passed improvements to state support for staffing standards, funding has increased to $725 per EL student for the 2021-2022 school year, which represents a 13.5% state supplement.34 If lawmakers had fully funded the VBOE’s recommendation to further improve staffing standards and provide additional staffing based on student English proficiency, the state supplement for EL student funding would have stood at $855 or 15.9% of state SOQ support for the 2021-2022 school year.35

In a comprehensive review of adequacy studies, the recommended additional funding for EL students beyond base student support ranges from a 39% to 200% supplement.36 The breadth of this range was in part due to the benchmarks set for what was deemed adequate: sometimes this meant achievement compared to average students, sometimes the benchmark was set below that. More recent state-level studies that take into account recommended additional funding weights for students range between 33% in Nevada37 to 41% in Michigan beyond base per-pupil state funding.38 In one of the most comprehensive adequacy studies to date, Maryland commissioned an independent study to determine the adequacy of their funding structures. They found that a 35% additional weight would address the needs of EL students,39 just slightly below the current national average of providing 39% more funding as found by a 50 state review.40 However, the study also recommended an upward revision to the base support Maryland provided per student to $10,880, which means the net average recommended supplement for EL students in the state would be $3,808.41

Direct state-to-state comparisons of funding adequacy can be challenging due to differences in cost of living, the types of EL services provided through state and local support, density of EL students in school divisions, varying definitions of adequacy, and general English proficiencies and needs of EL student populations. Yet even with those considerations, Virginia’s current EL funding, and even the Virginia Board of Education’s (VBOE) recommended increases to spending in their 2019 Standards of Quality (SOQ) revision, fall far below the lower bounds of what virtually all adequacy studies suggest for needed additional supplements.

In order to provide an equivalent funding supplement to what comprehensive adequacy studies suggested in Maryland and Michigan, the state of Virginia would need to increase SOQ spending for EL students from the current $725 to $1,880 or $2,202, respectively. In net, the state would need to spend an additional $132 million to $169 million annually on services for EL students.42 And even these estimates are likely low, since both of these adequacy studies in other states assumed a state funding base for students that was nearly twice as high as what Virginia currently spends.

Virginia’s Current EL Staffing Spending and What It Could Be at More Adequate State Supplements43

| Current Virginia spending (FY22) | With VBOE recommendations | At MD recommended supplement | At national average supplement | At MI recommended supplement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplement EL spending compared to other state aid | 13.5% | 15.9% | 35% | 38.7% | 41% |

| Additional state EL spending per student | $725 | $855 | $1,880 | $2,079 | $2,202 |

| State additional spending on EL students | $82.8 million | $97.7 million | $214.8 million | $237.5 million | $251.6 million |

Increasing Virginia’s EL teacher ratios and basing it on English proficiency levels of students is a positive first step that the VBOE has recommended in their 2019 and 2020 revisions of the Standards of Quality. With the share of student-aged children in Virginia not speaking English or not speaking English well increasing over recent years, focusing additional support on students with lower English proficiency is strategic for prioritizing resources. The state should go further than the VBOE recommendations and expand its support for EL students beyond just providing funding for EL specialist teachers. Like many other states, Virginia should provide more comprehensive support to allow for professional development of general education teachers who work with EL students on a regular basis, and more classroom and virtual resources that address the unique needs of students learning English.44 This would be a particularly practical step for furthering support of EL students given the persistent shortage of EL specialist teacher positions statewide.45 Furthermore, the state could embrace the multiple languages spoken by EL students by offering divisions more support for dual language programs. A growing body of research suggests these programs have significant positive academic and language acquisition impacts for EL and non-EL student outcomes.4647

Commission a Funding Adequacy Study

The firm from which Maryland and Michigan commissioned their independent studies had the capacity to write comprehensive reports on the state of funding, what adequate funding levels would be for what groups, and what Maryland and Michigan would need to do in order to be in line with high-performing states. While the national averages are a good starting point, Virginia could commission a similar study in order to have accurate and specific formula recommendations for groups like EL students, as well as the funding structure as a whole. The study would come at a cost, but it presents one of the most expedient and best ways to determine what resources it would take to make sure Virginia’s EL students were able to reach more adequate levels of success. Meanwhile, it seems reasonable to begin increasing state supplemental support for EL students to at least the lower-bound estimates of adequacy studies, ranging from 35% to 41%.

Fully Implement and Fund the Virginia Board of Education’s Revisions to the Standards of Quality

Underpinning so much of what impacts the effectiveness of Virginia schools is the categorical state direct aid allocated to divisions based on Virginia’s Standards of Quality (SOQs). This SOQ support from the state mostly comes in the form of paying a portion of salaries and benefits for essential school staff. Every two years, the education experts appointed to the Virginia Board of Education recommend revisions to the SOQs to meet students’ current needs and provide them with an adequate education. Lawmakers in the recent past have not usually funded the recommended VBOE revisions, and even made cuts to the existing SOQs more than a decade ago — funding that lawmakers have never fully restored.

In the most recent VBOE revisions, they recommend: restoring state funding for all of the support staff positions cut in the wake of the Great Recession; creating an Equity Fund to scale resources for high-poverty school divisions; improving the ratios of nurses, social workers and mental health staff; and increasing the number of EL teachers, principals, assistant principals, counselors, and mentors for new teachers in schools.48 These changes collectively would represent hundreds of millions of additional state dollars spent on schools each year, and would improve the quality and functioning of all schools across the state. While only one of the smaller spending recommendations would directly support EL students by increasing EL teacher to student ratios, the addition of support staff who could attend to unique health, social and emotional challenges of these students would be tremendously helpful for a strong and sustained recovery from the pandemic over the long term.

Virginia’s top education experts proposed these research-backed recommendations as the floor of what is needed to adequately support students, and fully funding the revised SOQs would help all students more fully participate in school settings, and particularly EL students who have faced more barriers to learning over the pandemic. While this represents the most costly solution offered in this report, Virginia has ample resources to meet this investment and should.49

Leveraging Community Resources To Address Barriers to Learning

Community-based organizations (CBOs) and local support services played a key role in providing essential services for immigrant families throughout the pandemic, and there are important lessons to be learned around how Virginia can replicate and coordinate these services in school settings for EL students. With many school divisions across the country failing to provide communications, distance-learning materials for EL students, and interpreters over the pandemic,50 CBOs that serve immigrant families and had strong pre-existing relationships in communities stepped up to provide new services to help these families navigate school systems. These same CBOs also often helped connect immigrant families to essential social services. Federal aid over the past year and a half excluded many immigrant families, and nearly 1 in 5 immigrant families with children avoided non-cash public benefits or other help with basic needs that was available last year out of fear of new federal rules. That is why it is so critical that organizations that have existing relationships with immigrant communities and serve students receive supplemental support to scale their efforts to break down barriers for families.

The state already provides direct funding to organizations that serve students in specific school settings, such as Communities in Schools,51 a nonprofit that provides wraparound services for students in school settings, and the state could replicate this model by funding CBOs that serve immigrant families and students. Another approach would be having school divisions regrant these dollars directly to local CBOs, allowing them to build a stronger collaborative relationship with each other and respond to the unique needs of EL students in their communities.

To scale school collaboration with CBOs and provide more comprehensive wraparound services to EL students, the state could begin investing in community school models. Community schools offer a holistic model for providing essential services to families — such as mental and physical health services, nutrition and housing support, tutoring and expanded learning time, family engagement, and community collaboration — so that children are able to focus on learning and not on other pressing needs. These schools seek to leverage available local, state, and federal resources and provide them to students and families at the school site. High-poverty schools can also draw down on federal grants that support full service community schools.

Community schools offer a holistic model for providing essential services to families so that children are able to focus on learning and not on other pressing needs.

There is growing recognition nationally, including from the U.S. Department of Education,52 that these models are research-backed and efficient in improving the well-being and outcomes of students who live in households experiencing poverty and for EL students,53 especially for EL achievement in math and English language arts.54 Many states have recognized the potential of these models and have invested in creating state offices that support the creation and maintenance of community schools, and offer grant funding to hire staff like community coordinators to run these programs.5556 Once schools have an initial staff person to begin coordinating community school services, they are often able to draw down on other available grant funding to sustain and expand their services.57

State lawmakers in Virginia have already taken the first step to advance these models, by commissioning the Virginia Department of Education to complete a report in 2019 offering guidance on how schools can transition to a community school model.58 The report, however, fell short in providing robust solutions for funding community school models in Virginia. As a result, since the release of the report, we have not seen many schools in Virginia adopt these models, and there remains a high barrier to entry. State funding could go a long way in jump-starting community school models at sites that could most benefit in Virginia, and make full use of the comprehensive blueprint the state has already created.

To effectively scale and create new community schools across Virginia, school sites and divisions must get clear direction and support (both resources and technical assistance) from the state. Virginia could take a two-pronged approach to expanding community school models that 1) build capacity statewide to support school sites and divisions as they implement these new models and 2) provide divisions with the highest poverty schools and schools with a high share of EL students with dedicated funding streams to establish and expand community schools. A first step could be establishing a Virginia Department of Education office that focuses on supporting community schools and developing a gauge from divisions of interest in piloting community school models. Lessons could be learned from the handful of community schools that exist in Virginia, including the pilot model in Fairfax County.

Require Automatic Enrollment in Advanced Courses, Allowing Students to Opt Out

As reviewed in the Virginia EL Student Outcomes in Context section, EL students are significantly less likely than their peers to graduate with an Advanced diploma, which requires taking classes such as Advanced Placement courses. Black, Latinx, and American Indian students are also less likely to graduate with Advanced diplomas. Correspondingly we see lower postsecondary enrollment for all these groups of students in Virginia, and VDOE has found students are significantly less likely to graduate on-time from higher education institutions if they do not have Advanced diplomas.

One novel approach to improving participation in advanced studies courses is to automatically enroll students who pass relevant state subject area tests, and ask them to opt out if they choose. Nationwide, several school divisions have experimented with this approach over the past several years, and Washington state is the first place in the country to require the approach statewide. The results from school divisions that have enacted this policy have shown a much higher share of students taking advanced classes who traditionally would have been less likely to enroll.59 Virginia lawmakers should consider legislation similar to Washington state to require enrollment of students in advanced courses if they meet certain achievement criteria, and could even go further by providing support that breaks down other barriers to participation in these courses, such as fees and the lack of availability in smaller divisions.

Increase Training for All Educators Working with EL students and Invest in Diversifying the Teacher Pipeline

Training required of teachers to work with EL students varies widely from state to state.60 Virginia offers teachers the opportunity to obtain an English as a Second Language endorsement, or certification, but it is not clear whether it is required to be considered an EL specialist teacher. Making the certification required could ensure that instructors are better equipped to meet the needs of EL students. And because the population of EL students is growing, many, if not most, teachers will interact with and teach students whose first language is not English.

General education teachers in Virginia must have some training to work with EL students for initial teacher licensure and renewal, but there is no requirement determining the quality of the training nor that school divisions have to provide it. Prioritizing professional development for general education teachers working with EL students could have a significant impact on EL student outcomes, especially since they will spend more time in school with these instructors than with specialists.61

In addition to training instructors, recruiting and retaining

diverse instructional staff should be a priority,

and could benefit EL students in particular.

Studies have shown that the presence of teachers of color in diverse faculties is important for students of color, producing higher levels of academic achievement and increased student access to advanced programs.

In addition to training instructors, recruiting and retaining diverse instructional staff should be a priority, and could benefit EL students in particular. Most EL students in the state are students of color, and a large majority are Latinx.62 Yet only a small percentage of teachers identify as either. Virginia’s teaching staff is overwhelmingly white and does not reflect the diversity of the student body. Over 75% of licensed teachers self-report as white, 11% as Black, and only 3% of teachers identify as Hispanic. As a result, many students do not get the opportunity to learn in a diverse environment and miss out on the benefits. Studies have shown that the presence of teachers of color in diverse faculties is important for students of color, producing higher levels of academic achievement and increased student access to advanced programs.63

There are several policy options that could begin to diversify the teaching workforce in Virginia, like expanding and strengthening teacher pipelines at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). For example, “Grow Your Own” programs aim to provide a pathway for members of the local community to become licensed teachers by offering various supports such as professional mentorship, financial assistance for state examinations, and experiential opportunities for students in the program. Significantly increasing state investment in the VDOE’s “Grow Your Own” pilot program could help strengthen pathways for Latinx teachers in the state. The program has already seen some success in Fairfax County Public Schools, where two Latinx teachers won grants through the program by teaching in the communities they attended as students.

Invest in Dual Language Instruction and Programing Outside the School Day

The state should expand its support of EL students by investing in dual language instruction models and policymakers should allow divisions more flexibility to invest state EL funding in different kinds of programming.

One type of instruction that has gained more attention in recent years is dual language programs. Dual language programs help students gain high levels of proficiency in English and in a partner language.64 This kind of program can take a few forms, but developmental bilingual and two-way immersion programs specifically enroll EL students. In the first type, all students are EL students with a common native language. In the second type, classrooms have a mix of students who speak English as a first language and students who speak a “partner” language.

Where some programs focus solely on learning English, dual language programs support continued development of another language the student knows. Just as students who are fluent in English still attend English classes, students have the opportunity to improve proficiency in their native language. And research has shown that dual language programs can be effective at improving student outcomes. In one study looking at EL students in Head Start programs, the researcher found that students in dual language classrooms showed greater average gains in both English oral proficiency and Spanish oral proficiency than students who received mainly English instruction with home language support.65 Native-English speakers also benefit by acquiring new language skills and having a larger group of more fluent peers to practice with.

Time spent outside of the classroom can also be important for EL students. As policymakers continue to work on addressing inequities deepened by the COVID-19 pandemic, resources should be directed toward after-school programs and other wraparound services for EL students, including programs run by CBOs. Fostering relationships between school districts and CBOs that have experience serving EL students and students from immigrant families can help schools meet the social, emotional, and academic needs of students.

VDOE could increase CBO capacity to offer these services by providing state-based grants or regrants through school divisions. Because many CBOs can operate after-school and summer programs and often have the infrastructure and expertise to do so, providing these groups additional state support could drastically scale these opportunities for students in the near term.

Conclusion

Each student brings with them different strengths, interests, and challenges, and being multilingual is a valuable strength that should be nourished in our schools. Yet persistent underfunding has left too many Virginia EL students behind. There are ample lessons to learn from other states that have committed to understanding the support it takes to meet EL student needs.

The General Assembly shall provide for a system of free public elementary and secondary schools for all children of school age throughout the Commonwealth, and shall seek to ensure that an educational program of high quality is established and continually maintained.

Constitution of virginia, Article VIII., Section 1.

Virginia has the resources and expertise to adequately support EL students through a wide array of policy solutions. Equitable and adequate direct state funding is a critical place to start, but other promising approaches such as community school models and automatic enrollment in advanced courses should be considered in conjunction, among other options. State lawmakers have the tools to uphold Virginia’s constitutional commitment to provide a high-quality education for all, including EL students.

Endnotes

- Jackson, C., and Mackevicius, C., “The Distribution of School Spending Impacts,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Jul 2021

- TCI analysis of fall membership data, Virginia Dept of Education, and NCES indicator data

- TCI analysis of fall membership data, Virginia Dept of Education

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- TCI analysis of 2019 American Community Survey microdata via IPUMS

- TCI analysis of public high school 4-year adjusted cohort graduation rate via EDFacts for school year 2018-19

- TCI analysis of 8th grade reading and math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress; states with measurable data

- It should be noted that all states are given the same set of instructions for accommodating EL students for NAEP tests based on language proficiency, but the level of needed and provided accommodation for EL students to meaningfully participate in these tests has been shown to vary by state. Nevertheless, NAEP serves as one of the only comprehensive national tests that can be used for cross-state comparisons.

- TCI analysis of aggregated 2015-2019 American Community Survey data

- TCI analysis of SOL pass rate data, Virginia Dept of Education

- “Examining the Impact of COVID-19 on Identification of At-Risk Students Spring 2021 Literacy Screening Findings,” University of Virginia School of Education and Human Development, Jul 2021

- Weyer, M., and Casares, J., “Pre-Kindergarten-Third Grade Literacy,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Dec 2019

- TCI analysis of Graduation, Completion, and Dropout data, Virginia Dept of Education

- Sugarman, J., and Lazarin, M., “Educating English Learners during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Migration Policy Institute, Sep, 2020

- TCI analysis of Graduation, Completion, and Dropout data, Virginia Dept of Education

- “Why diploma types matter,” Virginia Department of Education, Jun 2014

- TCI analysis of U.S. Dept of Education, Office for Civil Rights, Civil Rights Data Collection 2013-14

- “Education in a Pandemic: The Disparate Impacts of COVID-19 on America’s Students,” U.S. Dept of Education, Office For Civil Rights, Jun 2021

- Sugarman, J., “Legal Protections for K-12 English Learner and Immigrant-Background Students,” Migration Policy Institute, Jun 2019

- Sugarman, J., and Lazarin, M., “Educating English Learners during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Migration Policy Institute, Sep, 2020

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Stewart, C., “Words that Hurt: Anti-Sanctuary Bills Traumatize Children and Communities,” The Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, Mar 2018

- Carlson, P., “Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Academic Achievement of School-Aged Learners,” Concordia University (Saint Paul), Jul 2019

- TCI analysis of 2020-2021 fall membership data, Virginia Dept of Education

- Duncombe, C., “What’s Equitable When It Comes to School Funding: A National Report Sheds Light for Virginia Schools,” Mar 2019

- Jackson, C., and Mackevicius, C., “The Distribution of School Spending Impacts,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Jul 2021

- TCI analysis of FY 21 SOQ statewide totals, Virginia Dept of Education

- TCI analysis of FY 22 SOQ statewide totals, Virginia Dept of Education

- TCI analysis of FY 22 SOQ statewide totals, Virginia Dept of Education and FY22 cost estimates presented to Virginia Board of Education

- Sugarman, J., “Funding an equitable education for English learners in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, Aug 2016

- “Exhibit D,” Task Force on K-12 Public Education Funding Technical Advisory Committee – The Nevada Legislature, Apr 2014

- “Costing Out the Resources Needed to Meet Michigan’s Standards and Requirements,” APA Consulting and Picus Odden & Associates, Jan 2018

- “Final Report of the Study of Adequacy of Funding for Education in Maryland,” APA Consulting, Nov 2016

- Verstegen, D., “How Do States Pay for Schools? An Update of a 50-State Survey of Finance Policies and Programs,” Association for Education Finance and Policy Annual Conference, Mar 2014

- TCI Analysis of “Final Report of the Study of Adequacy of Funding for Education in Maryland,” APA Consulting, Nov 2016

- TCI analysis of FY 22 SOQ statewide totals, Virginia Dept of Education and adequacy estimates from Maryland and Michigan studies

- TCI analysis of FY 22 SOQ statewide totals, Virginia Dept of Education, FY22 cost estimates presented to Virginia Board of Education, adequacy estimates from Maryland and Michigan studies, and Verstegen national estimate

- “50-State Comparison: English Learner Policies,” Education Commission of the States, May 2020

- Sanchez, C., “English Language Learners: How Your State Is Doing,” National Public Radio, Feb 2017

- Oliva-Olson, C., “Dos Métodos: Two Classroom Language Models in Head Start,” Urban Institute, Oct 2019

- “Promoting the Educational Success of Children and Youth Learning English,” The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine, 2017

- “Draft BOE Letter to Governor and General Assembly,” Virginia Board of Education, 2021

- Jones, B., and Stewart, C., “High Capacity, Low Effort: Virginia’s School Funding is Low Compared to Most Rich States,” The Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, Sep 2021

- Garcia-Arena, P., “Spotlight on English Learners,” American Institute for Research, Oct 2020

- Lazarín, M., and Peña, J., “Rebuilding the U.S. Education System for the Nation’s English Learners,” Migration Policy Institute, Jun 2021

- “Frequently Asked Questions Using American Rescue Plan Funding to Support Full-Service Community Schools & Related Strategies,” U.S. Dept of Education, Jul 2021

- Darling-Hammond, L., et al., “Restarting and Reinventing School Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond,” Learning Policy Institute, Aug 2020

- Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., and Lam, L., “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence,” Learning Policy Institute, Dec 2017

- Blank, M., Jacobson, R., and Pearson, S., “A Coordinated Effort: Well-Conducted Partnerships Meet Students’ Academic, Health, and Social Service Needs,” Education Digest, Nov 2009

- Deich, S., and Neary, M., “Financing Community Schools: A Framework for Growth and Sustainability,” Partnership for the Future of Learning, 2020

- Ibid.

- “Virginia Community School Framework,” Virginia Dept of Education, Oct 2019

- Blad, E., “The Simple Policy Change That’s Getting More Students of Color in Advanced Courses,” Education Week, Mar 2020

- Quintero, D., and Hansen, M., “English learners and the growing need for qualified teachers,” The Brookings Institution, Jun 2017

- Mitchell, C., “Overlooked: How Teacher Training Falls Short for English-Learners and Students With IEPs,” Education Week, May 2019

- TCI analysis of fall membership data, Virginia Dept of Education

- Mendes, K., and Duncombe, C., “Modern-Day School Segregation,” The Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, Nov 2020

- Sugarman, J., “A Matter of Design: English Learner Program Models in K-12 Education,” Migration Policy Institute, Jun 2018

- Oliva-Olson, C., “Dos Métodos: Two Classroom Language Models in Head Start,” Urban Institute, Oct 2019