December 17, 2024

Segregation, Resource Equity, and K-12 Education In Virginia: A 200-Year Timeline

Every child in Virginia should have access to a high-quality public education that meets their needs, no matter who they are or where they live. Virginians — often led by Black students, parents, and community leaders — have been fighting for over 150 years to make that goal a reality. That work has taken the form of advocacy for additional resources, for more equitable access to the existing resources, and against the segregation in schools that enables inequitable access for resources. This timeline provides an introduction to some of the high (and low) points in that struggle, and is an extension of TCI’s 2021 report that dives deeper into the how and the why it matters of resource segregation and physical segregation in Virginia’s schools, and the fight against that segregation. We hope that this work will honor, strengthen, and inspire the ongoing struggle for well-funded, thriving, diverse schools across the commonwealth

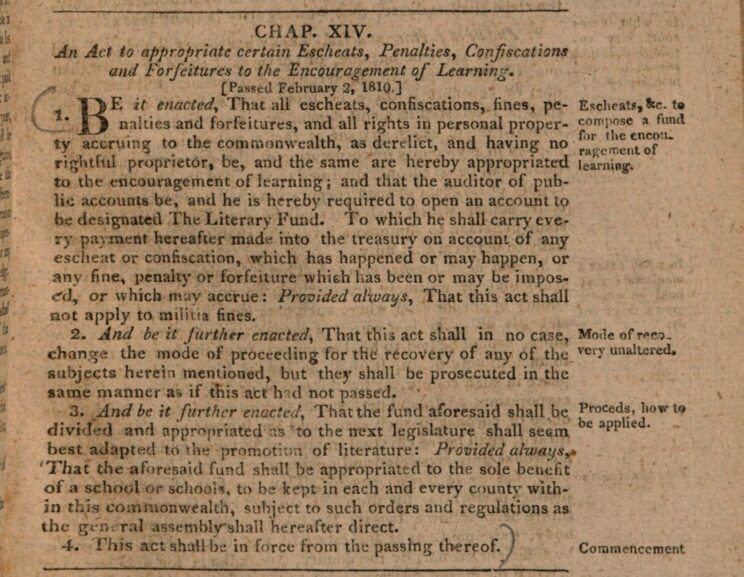

Establishment of Literary Fund

Virginia’s first foray into state funding for education was in the form of the Literary Fund, which was established to support the education of poor white students and was funded through unclaimed property, fines, fees, and bonds. This included revenue from the sale of runaway enslaved people.

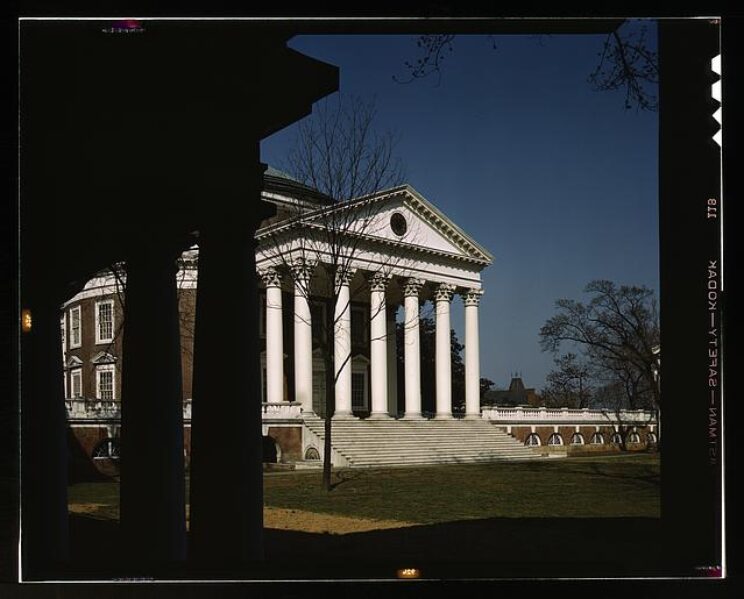

Some Literary Fund given to University of Virginia

A portion of Literary Fund money is given to the University of Virginia and, later, other white-only colleges, rather than being used solely for the education of poor (white) children.

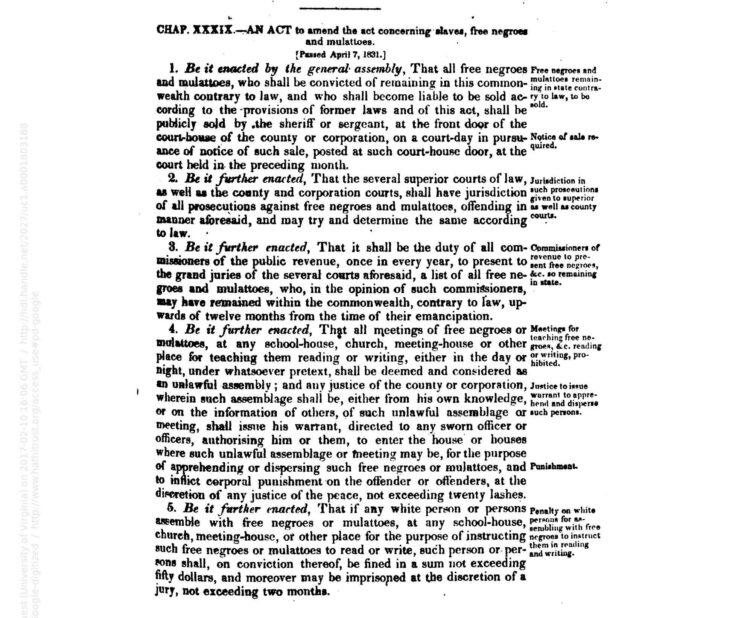

New Code of Virginia bans education for enslaved people

The first assembled Code of Virginia declares an unlawful assembly of any gathering of enslaved Black people, or mixed gathering of enslaved and free Black people, for the purposes of learning reading or writing.

Virginia outlaws educating free Black people

Code of Virginia declares any gathering for the purpose of teaching, reading, or writing to free Black people to be an unlawful assembly and prescribes punishments.

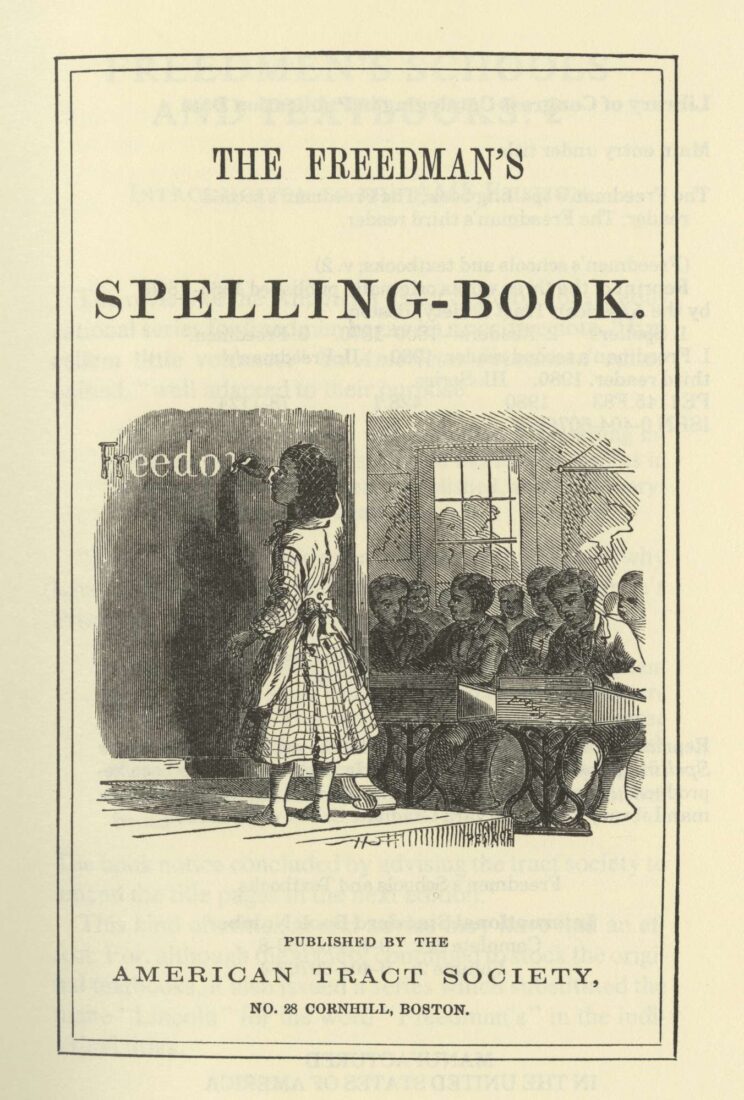

Education central to advancing goals

“In the decade of the 1860s, freedpeople attended schools by the thousands. They rebuilt burned-out school houses, armed themselves to protect threatened teachers, and persisted in the effort to be literate, self-sufficient participants in the larger American society,” states scholar Heather Williams.

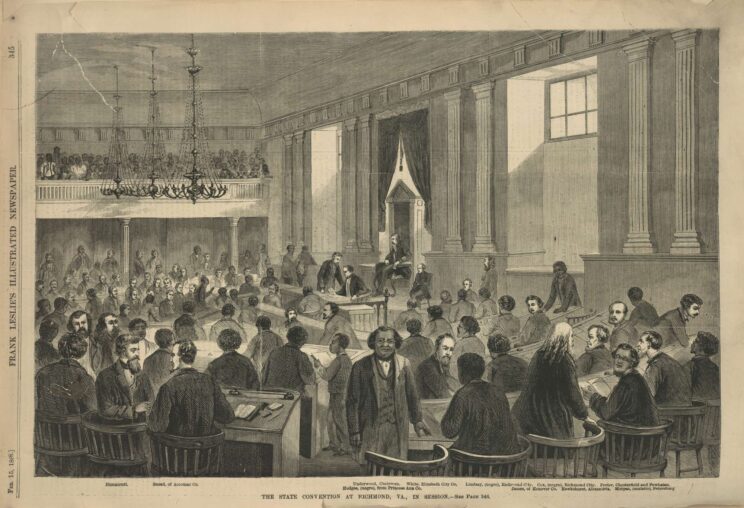

Creation of free public education

In Virginia, 24 Black representatives in the General Assembly joined with white Republicans to amend the state constitution to establish a free statewide system of public education, to be fully introduced in all counties by 1876.

Plessy v. Ferguson

The Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson upheld the legality of racial segregation for all public accomodations under the guise of separate but equal, giving way to legislation designed to disenfranchise Black voters and maintain fundamentally unequal systems of education.

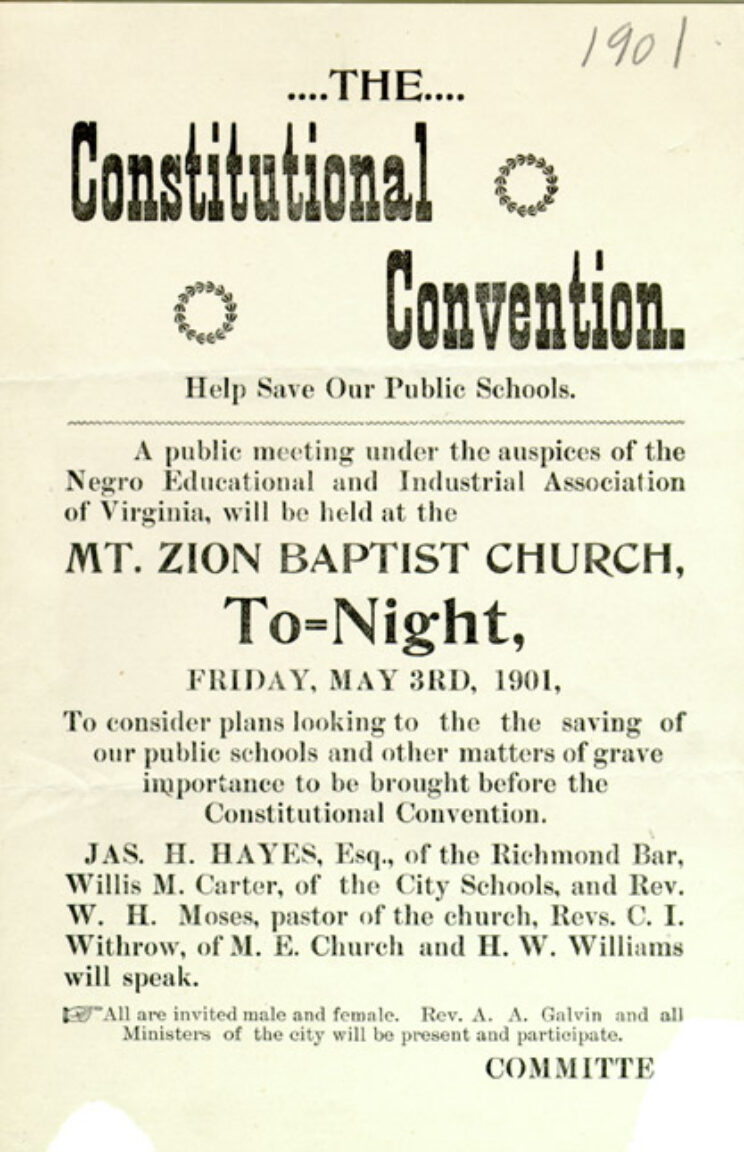

At the mercy of white-controlled state funding mechanisms

At the 1901-1902 Virginia constitutional convention, delegates granted local officials control over the distribution of school funds. Needless to say, white schools received the vast majority of these funds, even in districts with large black populations.

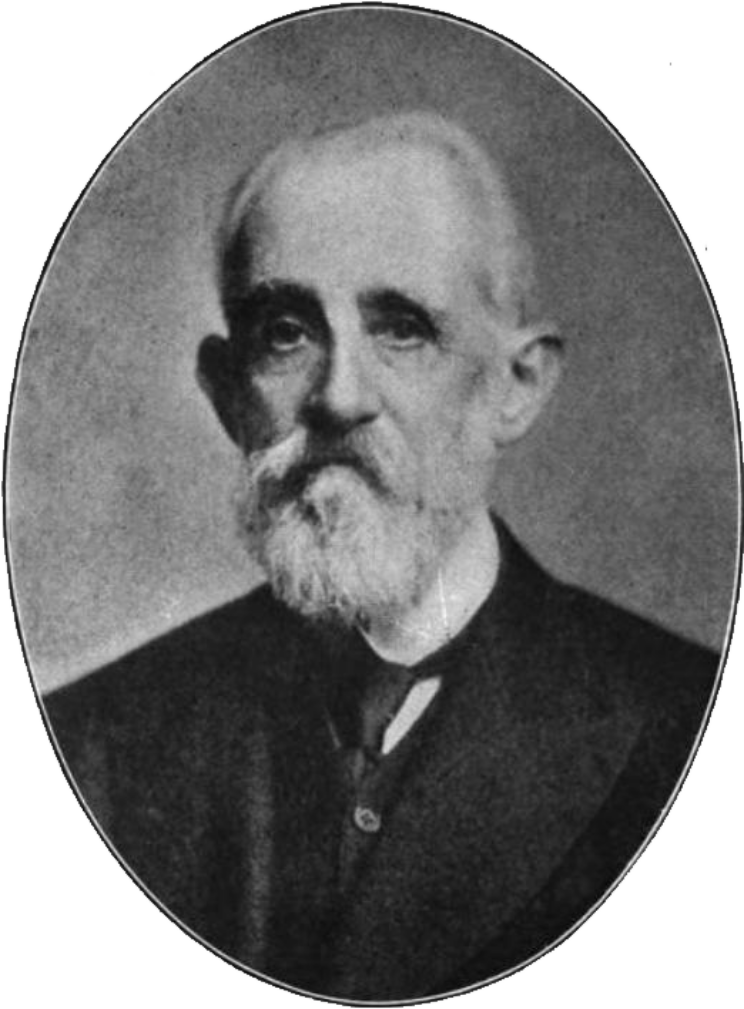

Undermining the quest for education

“We certainly do not need any high schools for our colored people in these counties,”said Richard McIlwaine, dismissing the idea that African Americans should have access to education beyond the primary grade level.

Opening of Black high schools

In 1909, Armstrong, the first Black high school in Richmond, opened its doors. Armstong was first known as the Richmond Colored Normal School. The school would be moved several times throughout the 1900s, until settling on its current location, 2300 Cool Lane, in Richmond, Virginia.

Further progress for Black students

Booker T. Washington in Norfolk became the state’s first accredited high school for Black students.

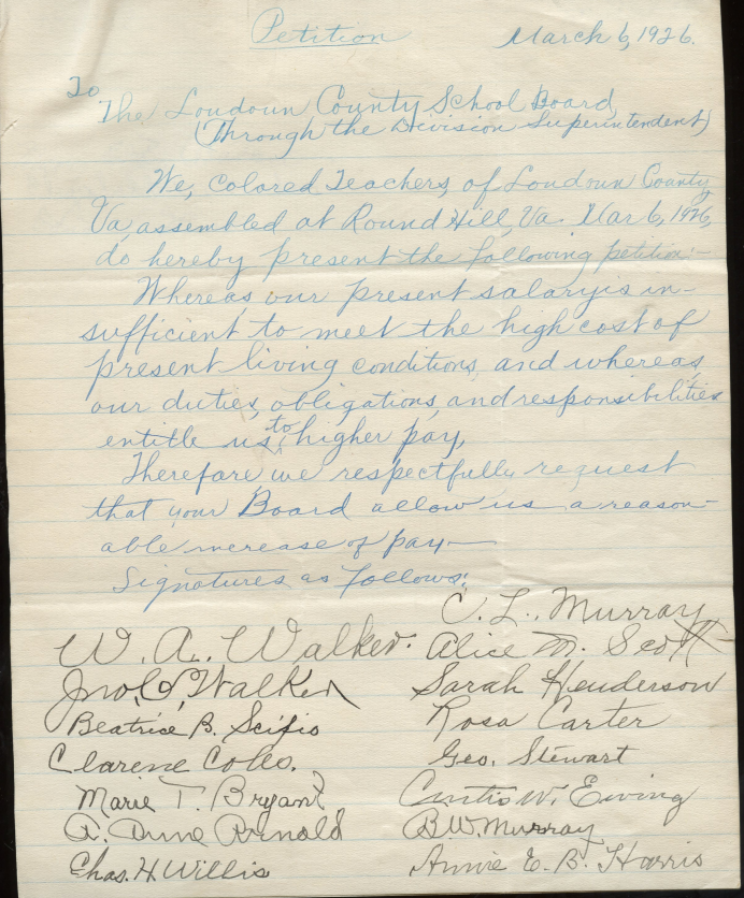

Black teachers in the state request raise

A group of Black teachers petition the Loudoun County School Board, writing, “Where as our present salary is insufficient to meet the high cost of present living conditions, and where as our duties, obligations, and responsibilities entitle us to higher pay, therefore we respectfully request that your Board allow us a reasonable increase of pay.”

More schools for Black students open; obstacles continue

The first Black high school in Charlottesville, Jefferson High, opened. In some cities like Charlottesville, local leaders worked to ensure that schools for Black children would be architecturally inferior to schools for white children.

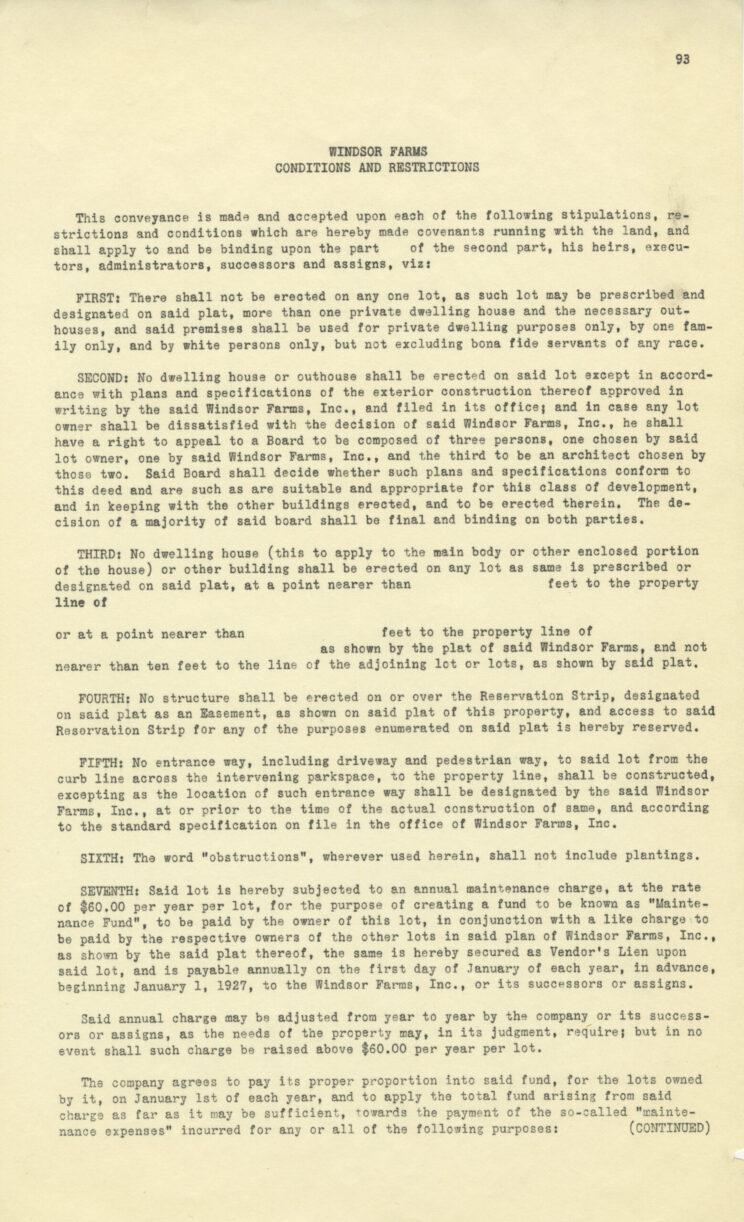

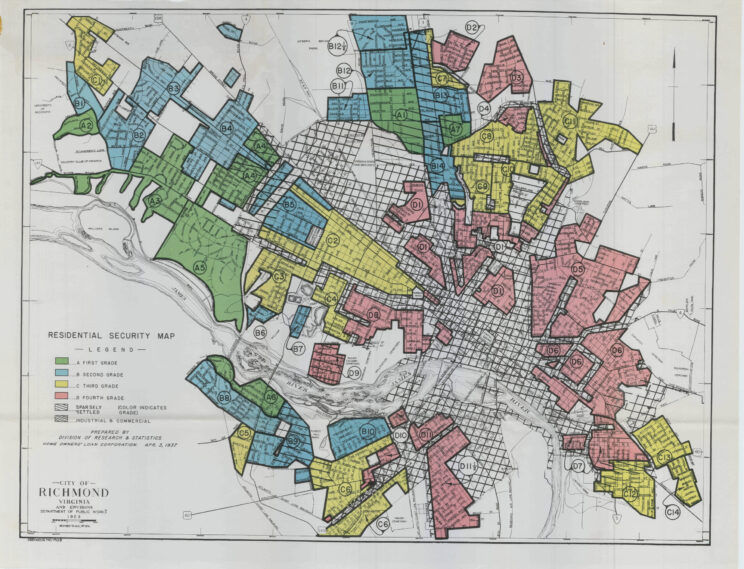

Housing segregation

The Federal Housing Administration was created, designed to increase access to housing for white home buyers and segregate neighborhoods. The FHA refused to insure mortgages in primarily Black neighborhoods in a process known as “redlining.” Maps were color coded to designate where it was “safe” to insure mortgages.

Punitive planning

“Urban renewal,” where cities use federal funds to clear “slums,” displaces families and destroys historic landscapes in Black communities. For example, the creation of I-95/I-64 cut through two of the largest and most historically rich neighborhoods in the city of Richmond —Jackson Ward and Navy Hill.

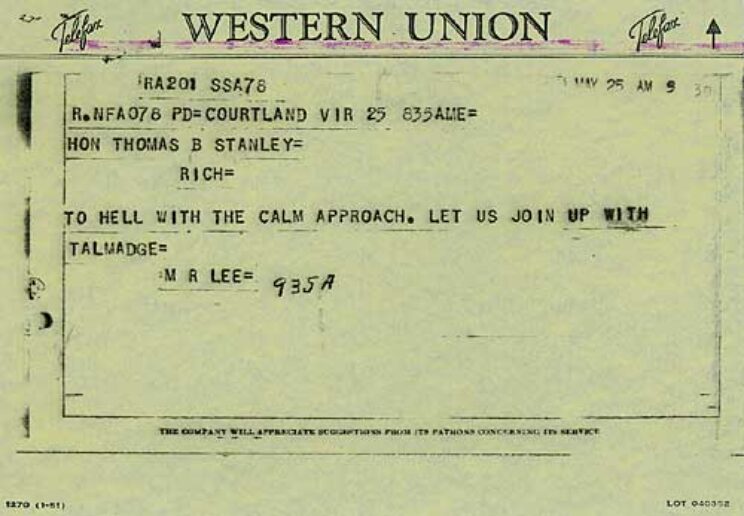

Closures

Several schools in Warren County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk were ordered to integrate but were seized and closed. The same year, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned the school closing law, and a federal court issued a verdict against the law citing the 14th amendment.

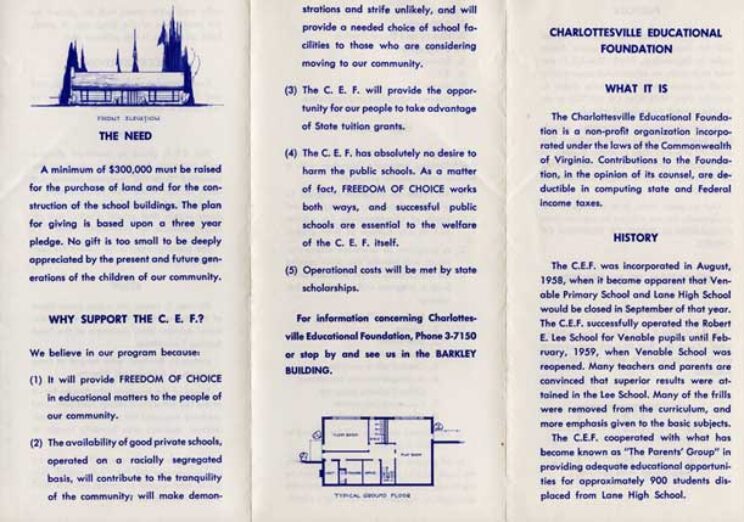

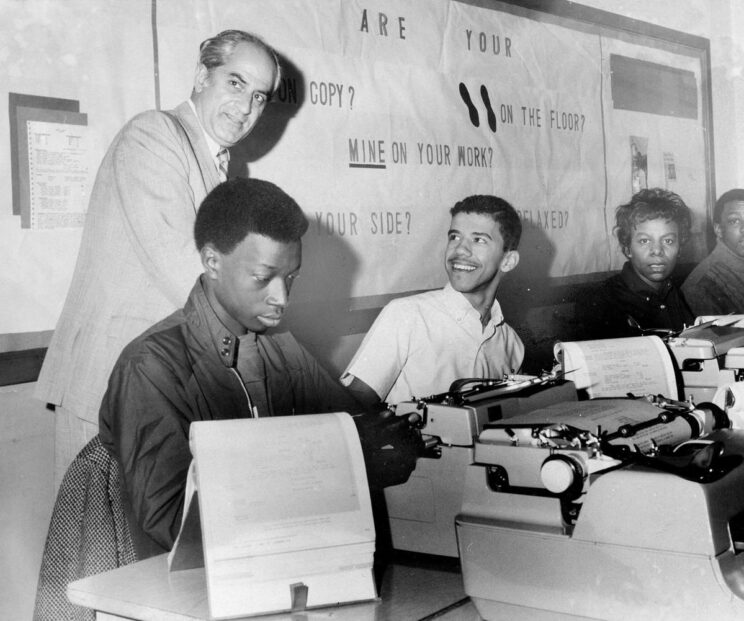

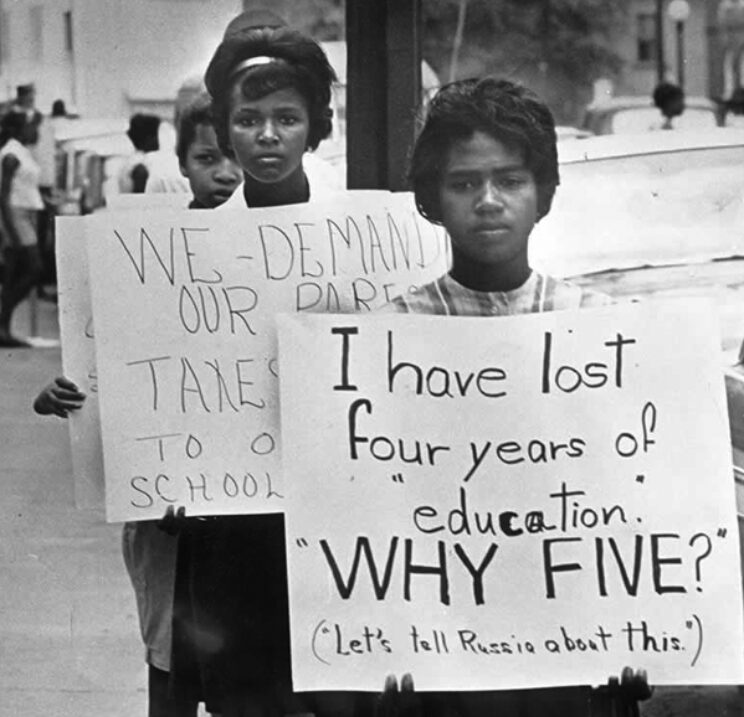

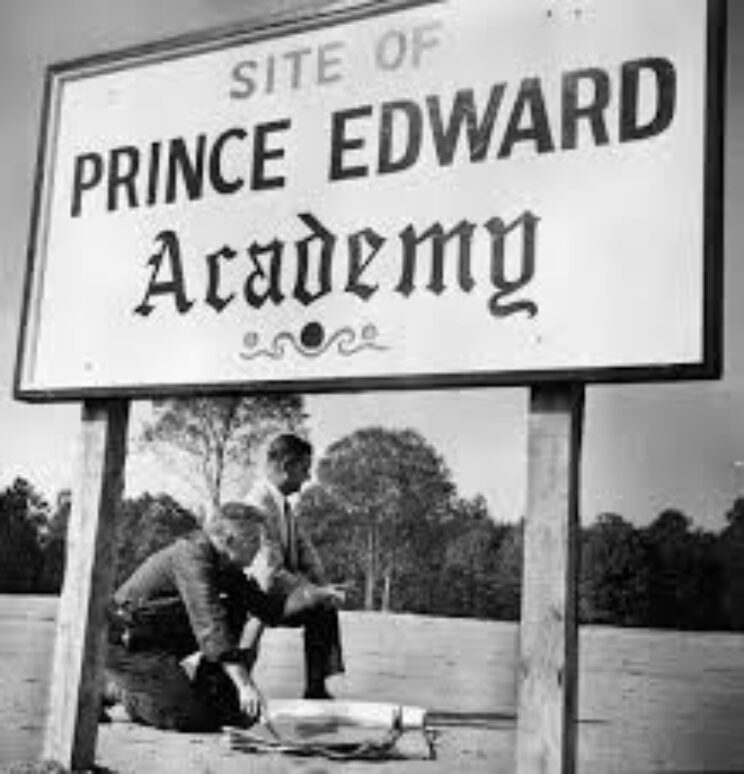

Ongoing resistance

Prince Edward County decided to close all of their schools entirely in opposition to integration, where Barbara Rose Johns and her classmates walked out just years prior. Some students miss out on some or all of 5 years of their education. Many white students continued to attend segregated private schools supported by state tuition vouchers and county tax credits.

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County

U.S. Supreme Court case Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County outlawed the use of public dollars to fund private schools, and schools reopened on an integrated basis.

School finance

Virginia ratifies a new constitution that would establish Standards of Quality for public schools, which would set the funding requirements needed to meet minimum standards for the first time. The foundation amount is unrealistically low, setting up the state to rely on voluntary contributions from local governments to fund essential services.

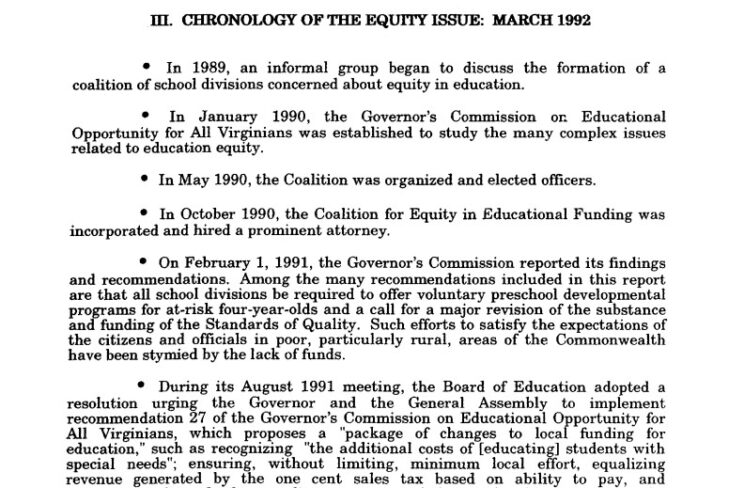

Study recommends equity improvements

The Commission on Educational Opportunities for All Virginians finds that state funding is inadequate for students living in poverty in 1991. The state creates a relatively small supplement called the At-Risk Add-On program following this report. Efforts by the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus have the grown program since, including in 2019 during a tense budget and tax negotiation.

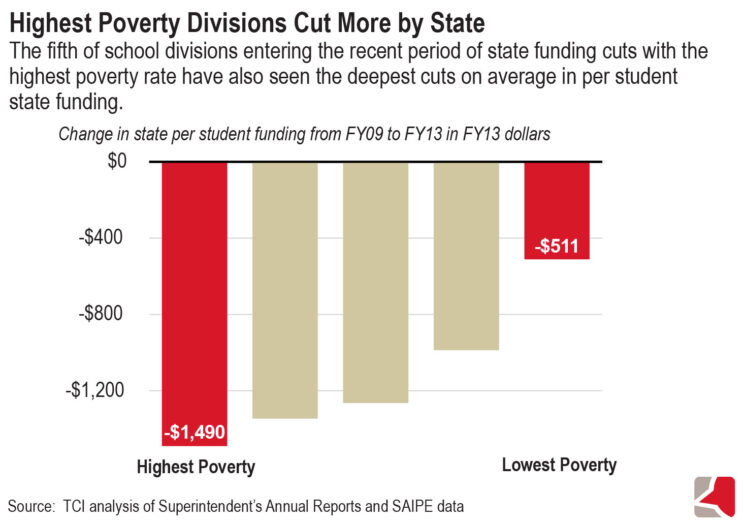

Deep, harmful cuts to school funding

In response to the Great Recession, lawmakers enacted cuts to K-12 funding that would have long-lasting impacts and hit low-income communities the hardest.

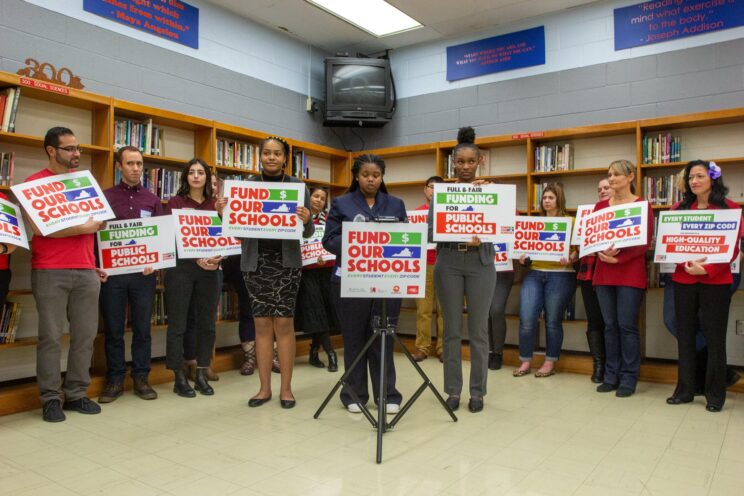

Fund Our Schools launches

Parents, students, teachers, and organizations launch a statewide coalition dedicated to making sure every child in every zip code has access to a high-quality public education. The campaign officially launches in December 2019, and advocates quickly began mobilizing and organizing across the state at budget hearings and throughout the General Assembly legislative session.

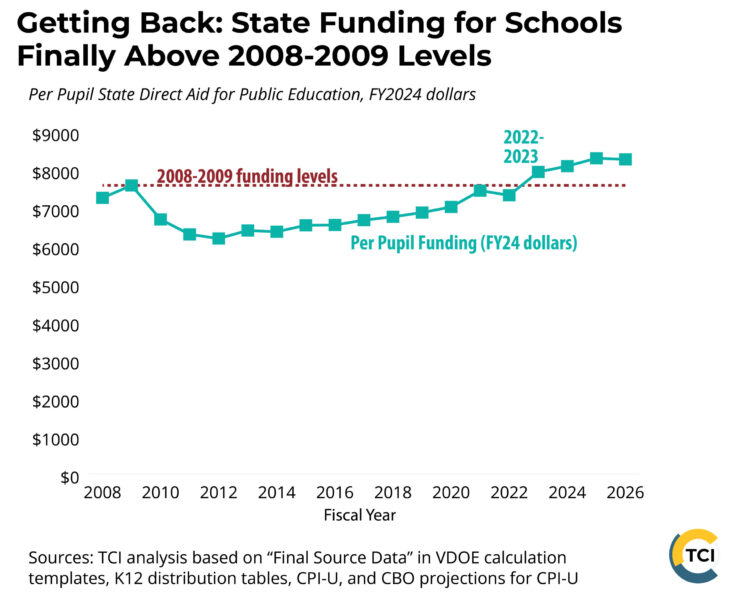

Adequacy improvements

In recent years, legislators began increasing the adequacy and equity of K-12 funding. In the 2022-2023 school year, per pupil state funding for direct aid for K-12 education finally exceeded 2008-2009 levels.

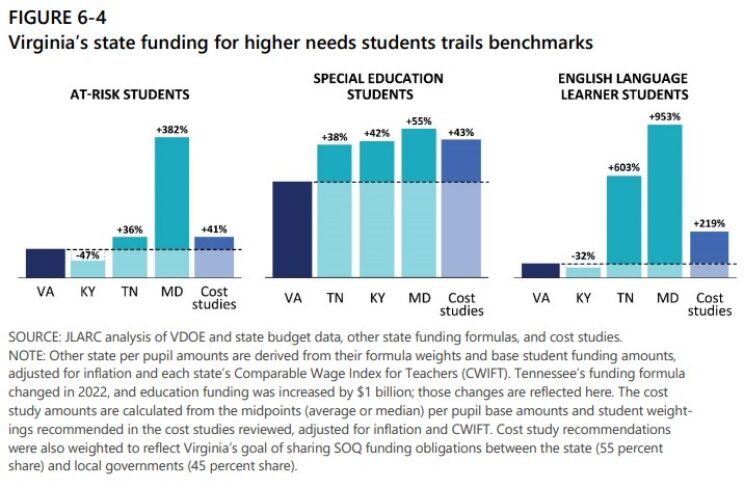

JLARC study

A major study by the state’s research agency, JLARC, identifies that Virginia “does not adequately account for higher needs students” and that the state’s funding formula provides “substantially less funding than actual division spending and benchmarks.” The report includes near- and long-term recommendations and policy options, including billions in recommended improvements.

Funding for high-poverty school divisions

Recognizing the particular importance of funding for educational outcomes for students in low-income households, between the 2015-2016 and the 2024-2025 school years legislators increased add-on funding for high-poverty school divisions from $90 million to $841 million. School divisions with the most Black students see the largest per pupil increases in state funding during this same time period.

Image Credits and Sources:

- 1810: Courtesy of HathiTrust

- 1818: Library of Congress

- 1819: Courtesy of HathiTrust

- 1831: Courtesy of HathiTrust

- 1865: Library of Virginia

- 1869: Library of Virginia

- 1870: VPM News

- 1896: The Roanoke Daily Times. (Roanoke, Va.), 19 May 1896. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 1901 (flyer): 1901, Library of Virginia Special Collections

- 1901 (McIlwaine): Public Domain

- 1909: Richmond Family Magazine

- 1911: Library of Virginia

- 1926: Courtesy of the Edwin Washington Project

- 1936: Courtesy of Mapping Inequality

- 1951: National Archives Catalog

- 1954: Library of Virginia

- 1955: Library of Virginia

- 1956: Library of Virginia

- 1957: Richmond Times-Dispatch

- 1958: Virginia Commonwealth University Library

- 1959: Moton Museum via The New York Times

- 1964: Academy Stories

- 1974: Richmond Times-Dispatch

- 1991: Report of the Commission to Review: Recommendations on Educational Opportunity Pursuant to SJR 251 of 1991

- 2009: TCI figure

- 2019: Julia Rendleman for The Washington Post

- 2019: Fund Our Schools Coalition

- 2009-2023: TCI figure

- 2023: JLARC