July 13, 2016

Shared Challenges: Underfunded Schools

Too many Virginia children are stuck in schools that lack adequate financial support and fail to meet the needs of their students. And this is more often the situation for students with limited English proficiency, Latino students – who are often the children of immigrants – and Black students than for other students.

In recent years, many of Virginia’s communities have faced challenges in providing sufficient support to maintain high-quality schools. And that’s true even in relatively affluent communities like Fairfax County. The erosion in support for Virginia’s schools hits immigrant families and those headed by African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and Latinos particularly hard, since these families are more likely to include children than families headed by non-Hispanic white Virginians and U.S. born Virginians. In fact, more than half of immigrant-headed households, and almost half of households headed by African-Americans, include at least one child, compared to 36 percent of households headed by non-Hispanic white Virginians.

And while many of Virginia’s children are impacted by these state funding cuts, Black and Latino students are hit the hardest.

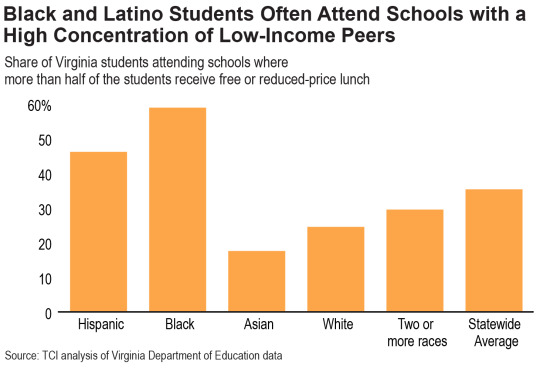

Virginia’s cities and counties continue to have a relatively high level of de facto segregation by both race and economic circumstances, and in the absence of proactive school integration efforts this drives schools to be segregated along the same lines. When well-off families cluster in certain neighborhoods to concentrate advantages for their children, it leaves other children left in clusters of concentrated disadvantage. And with immigrant communities and African-American communities both facing historical and contemporary barriers to employment opportunities, children in these communities are disproportionately stuck in schools of concentrated disadvantage. For example, Black children and those who identify as Hispanic or Latino are more likely than white children to attend schools where more than half the other students receive free or reduced-cost lunch – a good measure of the extent to which people in the community struggle to make ends meet. Concentrated poverty adds to the challenges facing children and schools, making it harder for Virginia’s Black and Latino children to get the education they need to get ahead.

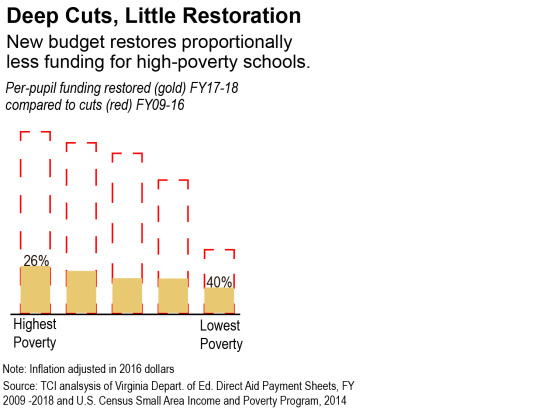

And despite the need, Virginia does less than it did before the recession to help local governments with school costs in communities of concentrated disadvantage. In 2018, the state is expected to provide the poorest school divisions an average of $939 less per student than was provided in 2009, after adjusting for inflation. For the wealthiest school divisions, the cut is just $263.

This concentrated disadvantage can be seen in outcomes for Black, Latino, and limited English proficiency students. Just 67 percent of Virginia’s students who are Black, and just 67 percent of students who have limited English proficiency (LEP), passed the math Standards of Learning (SOL) tests during the 2014-2015 school year, compared to 79 percent of all students. Similar discrepancies exist in other disciplines. And it is seen even in some of Virginia’s largest, most successful school divisions. For example, within Fairfax County, just 67 percent of Black third-graders and 70 percent of third-graders with LEP passed the English reading test.

These trends culminate in lower on-time graduation rates. While 93 percent of white students graduate high school on-time, only 86 percent of Black students and 84 percent of Hispanic students do. In addition, only 85 percent of economically disadvantaged students and 68 percent of LEP students graduated on time (2014-2015).

Part of making sure all students can get a top quality education means having schools and communities that serve people from all walks of life. History proves there is no such thing as a separate-but-equal education for disadvantaged children. Instead, segregation, whether de facto or by law, allows the hoarding of resources and opportunities for more advantaged families. Creating high-quality schools for all students, including African-American children and the children of immigrants, requires finding ways to address the school segregation that results from current patterns of residential segregation.

The second in a series of posts based on The Commonwealth Institute’s new report, We’re In This Together: African-American and Immigrant Communities Share Challenges, Policy Solutions. During July and August, we will be highlighting analysis and policy ideas from each section of the report. For more information about this report and its findings, please contact Laura Goren at laura@thecommonwealthinstitute.org.

Categories:

Budget & Revenue, Education