August 31, 2016

Solving Virginia’s Revenue Shortfall

Virginia is facing yet another round of potential cuts to vital protections for families and key investments in the future due to lagging state revenue, despite continued growth in the state’s economy. Lawmakers have plenty of options to address this latest challenge to our community, as long as they are willing to be fiscally responsible and avoid a cuts-only approach that harms Virginia’s families and communities.

At the root of the recent problem is a state economy that is growing but continues to feel the repercussions of slowing federal spending.

Seven years into the economic recovery from the Great Recession, many aspects of Virginia’s economy are finally positive. Job growth is strong and unemployment is low.

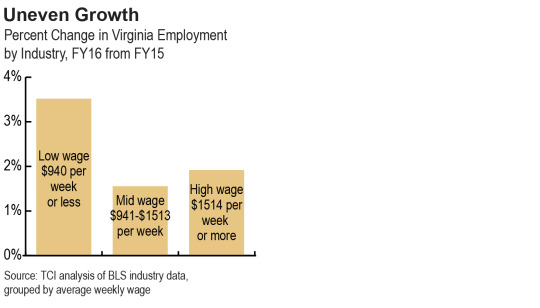

Unfortunately, some of the fastest job growth during the budget year that ended this past June was in relatively low-wage industries – such as the arts, entertainment and recreation sector – rather than in high-wage industries.

Jobs in industries paying $940 a week or less on average grew 3.5 percent during the past budget year, while jobs in mid-wage industries grew just 1.6 percent, and jobs in industries paying over $1,513 a week on average grew only 1.9 percent.

Most notably, there was another reduction in income tax payments from Virginians employed by federal contractors, a sector that helped sustain Virginia through the Great Recession, only to decline in the past three years.

Slower growth in jobs in high-paying industries may have contributed to the state revenue shortfall that is threatening key services for Virginia’s families and communities.

The state’s general fund revenue – the money that policymakers can use in ways they think is best for Virginia – grew 1.3 percent during the budget year that ended in June. That’s positive, but it was slower than originally forecast, resulting in $279 million less than expected.

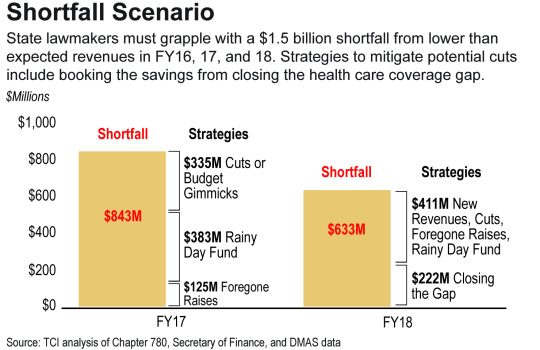

And, because each year’s budget is built on the prior year’s revenue, Virginia’s revenue shortfall compounds this budget year and next. So the $279 million shortfall from last year plus a $564 million shortfall this budget year means Virginia policymakers are faced with a total shortfall of $843 million this year and another $633 million shortfall next year. That totals almost $1.5 billion in reduced general fund resources for the two-year budget that started in July and ends in June 2018.

That’s the hole we’re in. And now lawmakers have to figure out how to fill it.

Since the planned salary increases for public employees that lawmakers passed last session were linked to hitting certain revenue projections, they’re already off the table. That saves $125 million this year and maybe more next year.

And policymakers also are considering whether to withdraw money from the state’s “rainy day fund” to deal with part of the shortfall. With an expected year-end balance prior to any withdrawal of only about $843 million, that could be a risky strategy.

While dipping into the rainy day fund helps cope with the immediate shortfall, using that money now places Virginia at risk for being unprepared for the next recession. Prior to the 2007 recession, Virginia had almost $1.2 billion in its rainy day fund. That money helped protect Virginians from even worse reductions in critical services during the tough recession years, and injected cash into the state’s economy when it was most needed.

Virginia began rebuilding the fund in 2013 and 2014, but then made a significant withdrawal in June 2015 to deal with that year’s revenue shortfall and another one in June 2016. If policymakers choose to make another withdrawal this year, the fund will end the budget year at about $460 million. And if it’s tapped again the following year, it could fall to about $230 million. It is troublesome that, during an economic expansion, the state’s rainy day fund would be tapped four years in a row and would be depleted to less than a quarter the level it was before the prior recession.

And even if Virginia does tap the rainy day fund, it won’t fill the entire hole – there will still be a significant state revenue shortfall in both the current and upcoming budget years.

The most obvious compromise, which would be a win-win for Virginia families and the state budget, is closing the health care coverage gap. If state lawmakers would join the 31 other states and Washington, D.C. that have prudently accepted the federal funds available to cover adults in Virginia who can’t afford health insurance, they would free up hundreds of millions of state dollars that currently pay for a patchwork of health care services for uninsured people. With proper planning and cooperation by key stakeholders, Virginia can close the gap starting July 2017 in a way that could save an estimated $222 million, based on TCI analysis of DMAS data. States across the country that have expanded Medicaid have seen exactly the type of savings Virginia could if lawmakers moved forward. For example, New Jersey is saving roughly $350 million per year.

Virginia lawmakers should also take a serious look at reforming the various tax breaks that constantly siphon off critical state revenues. The Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit, for example, is ripe for reform since it is costing taxpayers twice as much as initially thought, totaling $98 million in state budget year 2015. Perhaps the most egregious tax preference is the sales and use tax on watercraft, which is 2 percent of the sale but is capped at $2,000 no matter how expensive the boat is. So whether someone buys a $100,000 sailboat or a $10 million yacht, they both pay $2,000.

State officials also need to grapple with the fact that they have a bigger structural issue on their hands: The tax system that was designed for the 20th century is showing its age and has failed to keep up with the growth and changes in the state’s economy. One reason is that Virginia’s individual income tax structure has been virtually unchanged since 1987. As a result, Virginia’s top tax rate of 5.75 percent is the same for people with $10 million a year in taxable income and those with $18,000 a year in taxable income. Meanwhile, Virginia’s sales tax ignores a huge portion of what is bought and sold in Virginia. Namely, Virginia doesn’t tax the sales of most services because services weren’t as important a part of the economy when Virginia’s sales tax was developed. Nowadays, services represent 68 percent of what people buy in the US. That percentage has been growing for many years and will continue to grow, which means Virginia’s sales tax will become increasingly out of date and the state will continue to lack revenues needed for public investment that promotes prosperity.

These approaches would provide some breathing room to prevent further cuts to public education, health care, and vital investments in Virginia’s future. Chipping away at the shortfall is going to take compromise and sacrifices, and all of the burden should not fall on the shoulders of Virginia’s families who are struggling to get by.

Category:

Budget & Revenue